Lieutenant from Sobibor

On October 14, 1943, SS-Untersturmführer Ernst Berg entered the tailor’s workshop of the Sobibor concentration camp. It wasn’t that Berg was eager to communicate with the prisoners, but he was to have a uniform sewn for him, and the SS man was going to try it on. The uniform was ready, it was good, and it was the last impression of Berg’s life. As soon as he took off his belt and holster to change, an axe landed on his head. Thus began a remarkably successful uprising in the Nazi extermination camp.

The Toll-Houses of Captivity

Alexander Pechersky did not intend to become a hero, and it cannot be said that he went to his feat all his life. He was born in Kremenchuk, graduated from school, then worked as a clerk, led an amateur music club. In general, his pre-war biography looked cozy and unremarkable. Everything changed in 1941.

Pechersky was drafted into the army on June 22, in September he was promoted to quartermaster of the second rank (lieutenant rank), and sent to a staff position in an artillery regiment east of Smolensk. At that time, it was a quiet section of the front. However, just a few weeks later, one of the largest battles of World War II began: the Battle of Moscow.

This battle began with a grandiose catastrophe – the double encirclement of Soviet troops near Vyazma and Bryansk. Pechersky was surrounded along with others. His small squad wandered through the woods until they ran out of food and ammunition. A dozen soldiers with wounded in their arms had no chance of escape. In the end, the remnants of the shattered unit ran into an ambush and laid down their arms.

Nazi captivity was a nightmare in itself, but for Pechersky, the matter was further complicated by his Jewish roots. For a while, he managed to hide his origins. However, in captivity, he had to face another enemy who did not distinguish between nations and ranks – Pechersky fell ill with typhus. For several months, the lieutenant suffered from illness. The vitality of this man is amazing – he managed to survive the first winter of the war, which was the most difficult for Soviet prisoners. It is also indicative that the first thing Pechersky did when he recovered and got back on his feet was to try to escape. The dash escape was poorly prepared, so its participants were caught on the first day. The unfortunate fugitives were transferred to a camp near Minsk, and there, during a medical examination, it was discovered that they were Pechersk Jews. After that, the already bad attitude of the camp administration and guards deteriorated even more. In the Minsk camp, prisoners were poorly fed, poisoned with dogs for fun, and regularly beaten. One of Pechersky’s comrades was shot by the commandant just to demonstrate his marksmanship. During the Minsk prison, another group of prisoners tried to escape – they were caught and killed in the most sadistic way. In September 1943, prisoners from the Minsk camp began to be transported to camps in the Third Reich. Pechersky ended up in Sobibor, a camp for the extermination of Jews.

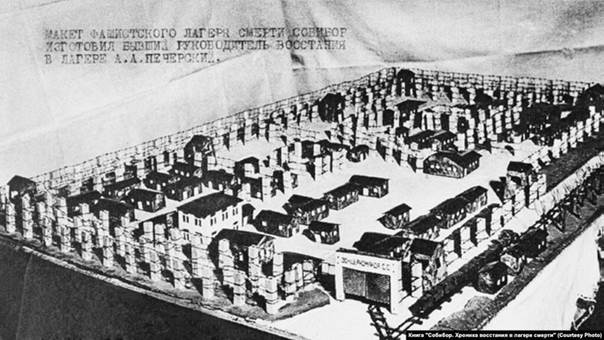

This camp, located in eastern Poland, had a dismal reputation even against the general background. It was founded in 1942 to exterminate the Jews, and in less than a year and a half, a quarter of a million people went to the other side of the world. Upon arrival, when the prisoners were being sorted, Pechersky said that he was a carpenter. It was a sensible idea: people who didn’t have any useful profession were quickly executed. Gas chambers, which became a symbol of the Nazi genocide, did not actually exist in all concentration camps, but Sobibor was one of them. People were herded into a building called a “bathhouse.” This structure could accommodate 800 people at a time. For a quarter of an hour, people were gassed, after which all that remained was to remove the corpses.

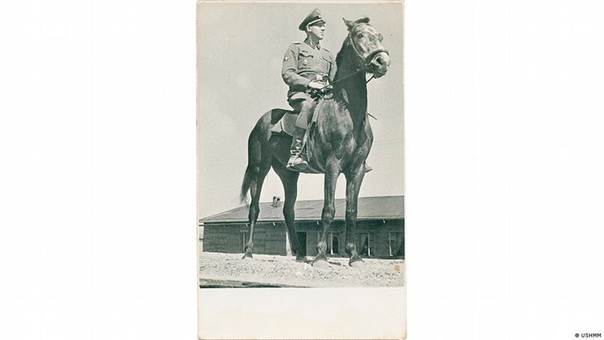

Sobibor consisted of three sectors. In one, sorting took place, the seizure of things from those who had something to take. After that, they were sent to another section of the concentration camp, where mass executions took place. Finally, in the third section of the camp, there were workshops where prisoners lived in poor conditions, but at least they were not exterminated immediately. The Nazis acted quickly, so there were rarely many people in the camp at the same time. Attempts to escape were quickly and brutally suppressed. Along with those who tried to escape, those who might have known about the escape, but did not report it, were shot. Karl Frenzel, the commander of the sector where Pechersky was imprisoned, participated in the executions personally, and killed more than forty people with his own hands. The conditions of detention were unbearable even for working prisoners – poor food, ferocious punishments for the slightest offense, murder.

Pechersky was well aware that in the event of an unsuccessful escape, he would go to the gas chamber himself. However, he also understood that if he escaped alone, the Nazis would kill his cellmates. If someone had escaped separately from him, the only road would have led, again, to execution. On December 2, one of the prisoners told Pechersky that he wanted to escape with a small group of comrades. However, the lieutenant dissuaded his comrade in misfortune from rash actions. The small group did not prepare the escape well – the prisoners did not have anything to make a passage through the barbed wire, they had no idea how to break through the minefield. However, Pechersky was not going to sit idly by. He decided to stage a mass riot and the flight of all who were able to escape. Moreover, from conversations with comrades in misfortune, Pechersky concluded that many would like to take a risk. There was no question of the leader of the uprising: the Red Army lieutenant had not only military experience, but also innate leadership qualities.

Riot in the camp

The lieutenant was well aware that the administration had informants among the campers. In addition, even without traitors, if many people knew about the escape, it would be very easy to puncture by accident. Therefore, only a few people knew about the planned uprising, whom Pechersky unconditionally trusted. From the old prisoners who had been in Sobibor for many months, Pechersky learned something about the security regime. At first, they thought of digging a tunnel. However, this was too difficult and risky, and the prisoners would run out of the tunnel too slowly. Therefore, the captives decided on a more radical method – to attack the guards and destroy the guards. To do this, they could use the tools of the workshops, besides, Pechersky ordered to make several dozen knives and stilettos in the workshops. In addition, scissors for cutting barbed wire were prepared.

Everything almost died because of one guy who, after another beating by the guards, wanted to escape on his own. Pechersky somehow persuaded him to wait, even threatening to kill him if he thwarted the plan of a general escape. Another problem was a capo named Brzecki. Rumors still circulated, the warden sensed which way the wind was blowing, and asked to participate in the case. After all, he was a prisoner, albeit with privileges. The prisoners, who knew about the escape, were exhausted with impatience. Moreover, the Germans were constantly finishing off those people who were completely weak from suffering. However, Pechersky had already completed the development of his plan.

The lieutenant’s idea was quite complicated. It was necessary to kill the leadership of the guards, and imperceptibly, so that the alarm would be raised as late as possible. Brzecki, who went over to the side of the insurgents, provided valuable assistance: he took Pechersky to the guard’s barracks, ostensibly for repairs, but in fact so that he could inspect it.

On October 14, on a warm, mild day, the prisoners prepared for an unprecedented uprising. The insurgents received detailed instructions a few hours before the uprising. The strike group was made up of Soviet prisoners with knives and homemade axes. The first Germans were to be killed by luring them into workshops under the pretext of trying on clothes made for them or taken from fresh prisoners.

Brzecki demonstratively beat the prisoners all day long to deflect suspicion. However, the whole thing almost fell through due to his unscheduled shipment to load logs. Kapo was indispensable: according to the general plan, he was to escort several rebels to a “sorting” camp to cut the lines of communication. He was replaced by another overseer who was in cahoots with the rebels. He took the group led by Boris Tsybulsky to the “second camp”, ostensibly for some kind of work.

Meanwhile, the first Nazi to be sacrificed, Ernst Berg, rode up on horseback to the tailor’s shop where the insurgents were sitting. Alexander Shubaev was already waiting for him with a hidden axe. As soon as the German took off his uniform and unfastened the pistol, Shubayev slashed him on the back of the head. The weakened prisoner was unable to kill him with a single blow, Berg began to scream, but on the second attempt he was finished. There was no turning back. A few minutes later, another German came into the workshop. A blow to the head and the second guard lay down next to the first. Several guards were called at different times to different workshops to try on boots, coats, overcoats and uniforms. So far, everything has been going great. At this time, Tsybulsky’s group cut the telephone lines. The prisoners also managed to disable the transport. Astonishingly, several camp guards have already been killed, cars and communications have been put out of action, and no one has yet raised the alarm. Commandant Frenzel could not be eliminated, but there was no time to wait for him to deign to appear within range. Pechersky gave the signal, and the uprising began openly. Almost all the prisoners found out about him at the last minute.

The captain of the guard at the gate did not have time to realize what was happening before he was killed. The insurgents already had the weapons of the guards in their hands, and they acted quickly, decisively, with the desperation of the doomed. More than four hundred people rushed to freedom. The surviving part of the guards realized what was happening, but the shooting could no longer stop anyone. The insurgents passed through the minefield in a wave of people. Those who walked first threw planks in front of them, trying to detonate the mines, but hardly with serious effect: dozens of people were killed by the mines. The armory was also not captured, but a wave of people was already rolling outside the camp.

Eighty prisoners died on mines and under the fire of the guards. 130 remained in the camp, some out of fear, some too weak to walk. But 340 people escaped into the forests. Behind them were 11 dead SS men.

In the forest, the fugitives parted ways. The Poles went to the west – that was their homeland. The Soviet prisoners moved east. As darkness fell, the crowd broke into small groups. Pechersky marched with a small detachment. By chance, they found Shubaev, who was lost in the turmoil of escape. However, now it was necessary to make our way through the autumn forests to a safe place. The Germans quickly got their bearings on what was happening and began a roundup.

Pechersky and eight of his comrades were on their way to the Bug River. They managed to spend the night on the farm. The owners did not hand over the fugitives, but warned that the crossings were guarded. However, Pechersky’s group crossed the river. In total, the Germans caught and killed about half of the escapees – 170 prisoners. All the prisoners who remained in the camp were also killed. The rest managed to break away from the chase in various ways.

Pechersky’s small detachment wandered through the forests for several days. However, they were lucky: Sobibor was not in the depths of the Reich. In the Belarusian forests of 1943 there was a life invisible from the outside, but tense. Soon the insurgents were picked up by partisans. Pechersky still considered himself a Soviet soldier, and naturally joined them. After the liberation of Belarus by the Red Army, Pechersky got into the formation of an assault battalion, and told his story to the battalion commander. The latter, shocked by Pechersky’s narrative, arranged for him to travel to Moscow to speak before the commission for the investigation of Nazi crimes. After that, he went to the front to finish fighting. Pechersky served in a specific formation – an assault battalion. These units were formed from officers who were in the occupied territory or in captivity. They were not considered penal battalions, their employees were not deprived of their ranks, but stormtroopers, as well as penal officers, operated in the most dangerous areas. In August 1944, Pechersky was wounded in the thigh, decorated and discharged.

Subsequently, Pechersky acted as a witness at the trials of collaborators who served as overseers in Sobibor. The Germans liquidated the concentration camp, but many criminals were brought to justice. Commandant Frenzel was sentenced to life imprisonment in the 1960s, but was pardoned at the end of 1992 after serving 30 years. The commandant of Sobibor at the time of the uprising, Franz Reichleitner, continued to serve in the SS, but was killed by Italian partisans in January 1944.

Stanislav Schmaizner, one of Pechersky’s group. He died in Brazil in 1989.

The story of Pechersky became widely known, and in 1987, Rutger Hauer played Pechersky in the first film based on this story. The rebel officer died in 1990 in Rostov-on-Don.

Only a little more than fifty insurgents of Pechersky’s group survived the war. Among others, one of the most active insurgents, Alexander Shubaev, was killed, and Boris Tsybulsky, whose group cut off telephone communications in Sobibor, died of illness. However, he died in battle, not under the bunk. The fate of many of the fugitives has never been traced. On the other hand, one of the Sobibor soldiers, Semyon Rosenfeld, left his mark right on the Reichstag: this soldier scratched the inscription “Baranovichi-Sobibor-Berlin” on the column.

Uprisings in the Nazi extermination camps were rarely as successful as those at Sobibor. Only the Buchenwald uprising of April 1945 was equally effective. Pechersky and his comrades were able to survive where almost no one survived, and to win where it was impossible to win.

Author – Evgeny Norin,