Russophobia is external

1. Tyutchev

The term Russophobia dates back to September 20, 1867.

On this day, the remarkable Russian poet and diplomat F.I. Tyutchev, in a letter in French to his eldest daughter Anna, who was married to I.S. Aksakov, expressed the idea of the need to write an article in which “it would be necessary to consider the modern phenomenon, which is acquiring an increasingly pathological character. We are talking about the Russophobia of some Russians, and very revered ones… They used to tell us, and indeed they believed, that in Russia they hated the lack of rights, the lack of freedom of the press, etc., etc., that it was precisely they who loved Europe so dearly, that it undoubtedly possessed everything that Russia did not have. And what do we see now? As Russia asserts herself more and more in her pursuit of greater freedom, the dislike of these gentlemen for her only intensifies. On the other hand, we see that none of the violations of justice, morality, or even civilization that are tolerated in Europe have in the least diminished the predilection for it. In a word, in the phenomenon I have in mind, there can be no question of principles as such, only instincts are at work here, and it is the nature of these instincts that must be understood.

By “some Russians” Tyutchev meant Turgenev and his famous conversation with Dostoevsky.

2. Dostoevsky and Turgenev

In a well-known letter to A. N. Maikov on August 16, 1867, Dostoevsky tells about his life in Dresden, Germany:

“In Germany, I ran into a Russian who lives abroad permanently, goes to Russia every year for three weeks to get an income and returns back to Germany, where he has a wife and children, all of whom are German.

By the way, I asked him, “Why did he expatriate?” and he answered literally (and with irritated impudence): “Here is civilization, and here is barbarism. In addition, there are no nationalities here; I was in the carriage yesterday and could not distinguish between a Frenchman and an Englishman and a German. Civilization must equalize everything, and then we will only be happy when we forget that we are Russians and everyone will be like everyone else.”

I am translating this conversation literally. This man belongs to the young progressives, however, he seems to keep himself aloof from everyone. They turn into some spitz, grumpy and squeamish, abroad.”

Dostoevsky then moved to Baden, where he met Turgenev. That was the time when the novel “Smoke”, as they say, failed in Russia. The writer was scolded, they even wanted to deprive him of his nobility.

Dostoevsky frankly admits that the book “Smoke” irritated him with its basic idea, which “he [Turgenev] himself told me that the main idea, the main point of his book, is the phrase: ‘If Russia had failed, there would have been no loss or unrest in mankind.’ He told me that this was his core belief about Russia.” This “main idea” is put into the mouth of Potugin in the novel.

Dostoevsky writes about his conversation with Turgenev: “He cursed Russia and the Russians in an ugly, terrible way. But here is what I have noticed: all these liberals and progressives, chiefly those of Belinsky’s school, find it their first pleasure and satisfaction to criticize Russia. The difference is that Chernyshevsky’s followers simply criticize Russia and openly wish it to fail (mostly to fail!). These, the offspring of Belinsky, add that they love Russia. And yet not only do they hate everything that is a little original in Russia, so that they deny it and at once turn it into a caricature with pleasure, but that if at last they were really presented with a fact which could no longer be refuted or spoiled in a caricature, but with which they must certainly agree, it seems to me that they would be in pain. They are miserable to the point of pain, to despair.

I noticed that Turguéneff, for instance (as well as all those who have not been in Russia for a long time), are decidedly ignorant of the facts (although they read the newspapers), and have grossly lost all sense of Russia, do not understand such ordinary facts, which even our Russian nihilist no longer denies, but only caricatures in his own way. By the way, Turgenev said that we must crawl before the Germans, that there is one common and inevitable road to all, and that is civilization, and that all attempts at Russism and independence are swinishness and stupidity. He said that he was writing a long article on all Russophiles and Slavophiles. I advised him, for convenience, to order a telescope from Paris. “For what?” he asked. “It’s a long way from here,” I answered, “you point your telescope at Russia and look at us, otherwise it’s really hard to see.” He was terribly angry.”

Dostoevsky retorted that “the black people here are much worse and more dishonest than ours, and there is no doubt that they are stupider. Well, you are talking about civilization; Well, what civilization has done to them, and what they can boast of to us so much!”

Turgenev “turned pale (literally nothing, I am not exaggerating anything!) And he said to me, “By saying this, you are offending me personally. Know that I have settled here definitively, that I consider myself a German, not a Russian, and I am proud of it!”

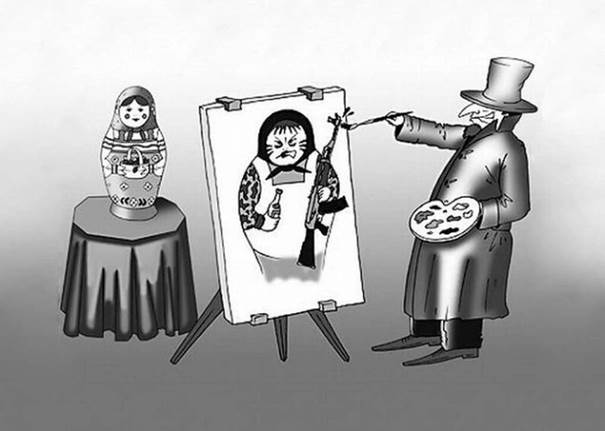

2.2. Russophobia caricature

A phobia implies a persistent fear and hatred of its source, and there are hardly any neighboring peoples in the world whose representatives have never had such feelings for each other.

And yet, I don’t think any hostile comment or attack on the Russian people should be considered Russophobia. Russophobia is not just hostility to Russia, and certainly not any criticism.

In its highest manifestation, Russophobia is a Western ideology that asserts the evil nature of the Russian people. According to it, the Russian people are endowed with certain unique qualities that determine their craving for everything base. Russians seem to be incapable of all that constitutes human dignity in other peoples, which is explained genetically and culturally and historically. The logic of Russophobia is based on the juxtaposition of Russian and Western as bad and good. Russia appears as an existential enemy of the West and of everything that is perceived in Western culture as specifically “Western” – freedom, democracy, human rights, etc. From this, conclusions are drawn about the need to fight Russia and destroy everything that constitutes Russianness – physical or cultural, depending on specific interpretations.

The closest analogue of such an ideology is anti-Semitism. Until about the eleventh century, the attitude towards Jews in Europe was quite tolerant. (The Jews were seen as the guardians of the Old Testament Law, witnesses to the crucifixion of Christ, and a people called to Christianity shortly before the end of the world.)

However, in the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, the attitude towards Jews in the West changed dramatically, which was expressed not only in the growth of hostility, but also in the emergence of a whole host of concepts justifying an intolerant attitude towards Jews, as well as the practices arising from them. The Jews began to be seen as servants of the devil, they were accused of kidnapping Christian babies and ritual murders, desecrating communion, poisoning wells and in general spreading all sorts of infections, preparing a conspiracy against Christians, etc. From the end of the thirteenth century there are facts of the expulsion of Jews from cities and entire countries.

3. The burning of Jews on charges of desecrating the Eucharistic bread. Nuremberg. XV century

In the second half of the 19th century, it was conceptualized in terms of racial theory, which soon led to large-scale genocidal practices. Thus, anti-Semitism is a system of specific ideas about Jews as a special ethnic community, a special ideology with its own genesis and history of development.

It seems that in the case of Western attitudes towards Russia and Russians, we are dealing with a phenomenon of this kind. By the way, the concept of anti-Semitism was first used at about the same time as Russophobia (in Wilhelm Marr’s work “The Path to the Victory of Germanism over Jewry”, 1880).

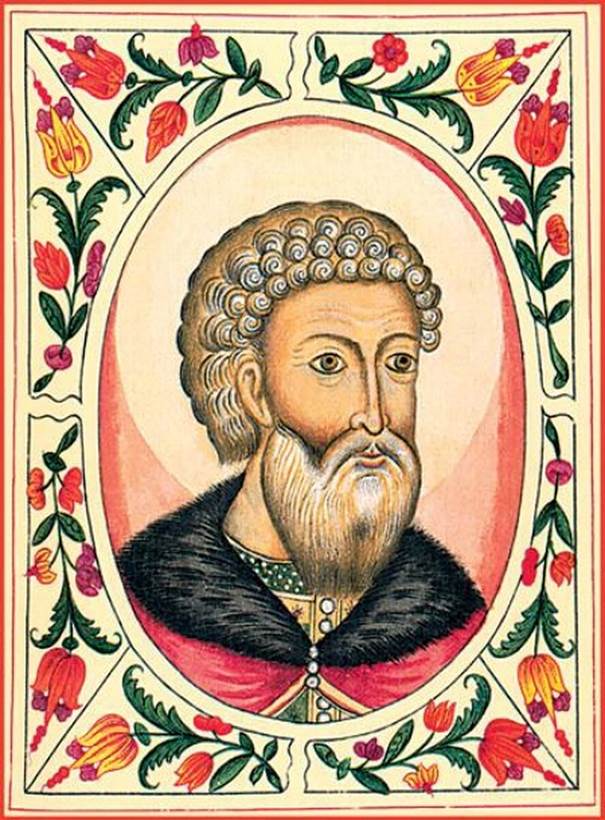

4.1. Ivan III

The European “discovery” of Russia took place at the end of the 15th – 16th centuries.

Some historians also call the first sovereign of all Russia, Ivan III Vasilyevich, the first Russian Westernizer, drawing a parallel between him and Peter the Great.

Indeed, under Ivan III, Russia was advancing by leaps and bounds. The Mongol-Tatar yoke was thrown off, and the specific fragmentation was destroyed. The high status of the Muscovite sovereign was confirmed by the adoption of the title of Sovereign of All Russia and the prestigious marriage to the Byzantine princess Sophia Palaiologos.

In the mid-80s of the 15th century, Emperor Frederick III of Habsburg offered Ivan III to become a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, promising to grant him the royal title in return, but received a proud refusal: “By the grace of God, we have been sovereigns in our land from the beginning, from our first ancestors, and we do not want to be installed as a kingdom from anyone before, and we do not want it now.”

In order to emphasize his equality with the emperor, Ivan III adopted a new state symbol of the Muscovite state – the double-headed eagle. The marriage of the Muscovite sovereign with Sophia Palaiologos made it possible to draw a line of succession independent of the West for the new coat of arms – not from the “first” Rome, but from the “second” Rome – Orthodox Constantinople.

The oldest image of a double-headed eagle in Russia is imprinted on the wax seal of Ivan III, attached to the charter of 1497. Since then, the sovereign eagle has signified the state and spiritual sovereignty of Russia.

4.2. Seal of 1497 with an eagle

In short, Russia has become a full-fledged sovereign state. But national self-assertion had nothing to do with national insularity. On the contrary, it was Ivan III, more than anyone else, who contributed to the revival and strengthening of Moscow’s ties with the West, with Italy in particular.

Ivan III kept the visiting Italians with him in the position of court “masters”, entrusting them with the construction of fortresses, churches and chambers, the casting of cannons, and the minting of coins. Especially famous among them was the outstanding Italian architect Aristotle Fioravanti, who built the famous Assumption Cathedral and the Faceted Chamber in the Moscow Kremlin (named so on the occasion of its decoration in the Italian style – facets). In general, during the reign of Ivan III, thanks to the efforts of the Italians, the Kremlin was rebuilt and decorated anew. The Angel’s Castle in Rome is completely Kremlin walls at the back.

Thus, thanks to the efforts of Ivan III, the Renaissance flourished on Russian soil.

In addition to masters, ambassadors from Western European sovereigns often appeared in Moscow. And, as was seen in the example of Emperor Frederick, the first Russian Westernizer was able to talk to Europe on an equal footing.

To the time of the reign of Ivan III Vasilyevich and his son Vasily III belong the first detailed notes of foreigners about Russia, or Muscovy, if we adhere to their terminology.

The Venetian Josaphat Barbaro, a merchant, was struck first of all by the well-being of the Russian people. Noting the richness of the Russian cities he saw, he wrote that in general the whole of Russia “abounds in bread, meat, honey and other useful things.”

Another Italian, Ambrogio Cantarini, emphasized the importance of Moscow as an international trade center: “Many merchants from Germany and Poland gather in the city throughout the winter,” he writes. He also left an interesting verbal portrait of Ivan III in his notes. According to him, the first sovereign of all Russia was “tall, but thin, and in general a very handsome man.” As a rule, Cantarini continues, and the rest of the Russians are “very beautiful, both men and women.” As a devout Catholic, Cantarini did not fail to note the unfavorable opinion of Muscovites about Italians: “They believe that we are all lost people,” that is, heretics.

Another Italian traveler, Alberto Campenze, wrote a curious note for Pope Clement VII, “On the Affairs of Muscovy.” He mentions the well-organized border service of the Muscovites, the prohibition of the sale of wine and beer (except on holidays). The morality of the Muscovites, according to him, is beyond praise. “To deceive one another is regarded by them as a terrible, heinous crime,” writes Campenze. Adultery, violence, and public debauchery are also very rare. Unnatural vices are completely unknown, and perjury and blasphemy are not heard of at all.”

But this belongs to the genre of travel notes.

The first detailed treatise on Russia came from the pen of Sigismund Herberstein, he was one of the brilliant Austrian diplomats, and he also knew the Slavic dialects. 20 years after his last visit to Russia, he published the book “Notes on Muscovy”. In Russia, this book was first published in 1862. This work set the ideal “type and form of the narrative about Russia” in the West. In the second half of the 16th century, it was reprinted 22 times, that is, on average once every two years. The main ideas of these “Notes” formed the basis of the Western perception of Russia, one could say, created its image in Western culture.

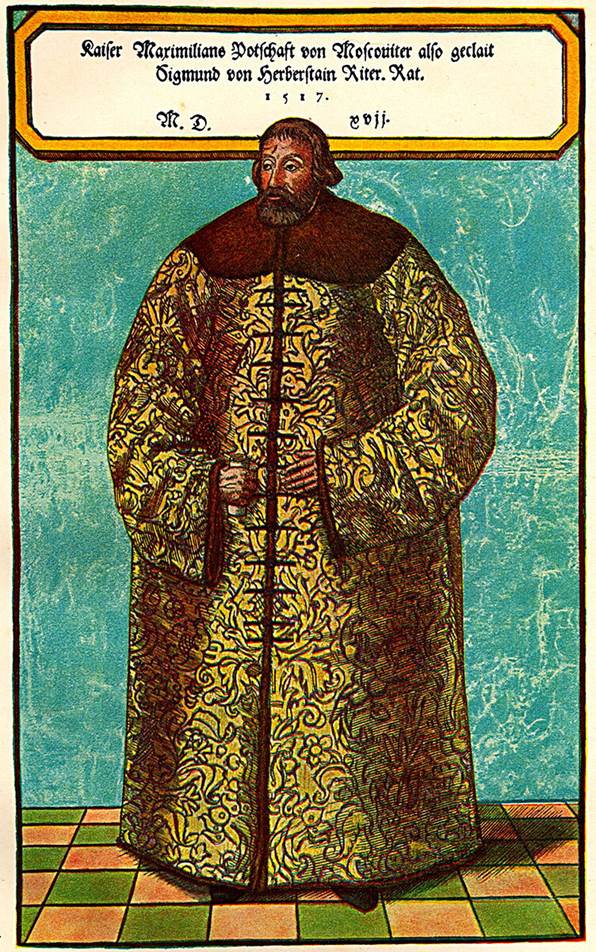

5. Sigismund Herberstein in a fur coat granted to him by Tsar Vasily III in 1517.

Herberstein was an ambassador to the Habsburg court, whose goal was to persuade Moscow to participate in joint anti-Turkish campaigns, which also required reconciling it with Lithuania. However, both embassies (1517 and 1526) were unsuccessful. In his Notes, Herberstein tried to justify the actual failure of his missions by the characteristics of the “Muscovite” people themselves and the impossibility of allied relations with them.

Muscovites, according to Herberstein, are prone to murder, violence, robbery, and other criminal acts. At the same time, Russians are very fond of drunkenness and “Venus pleasures”. In addition, they live in conditions of cruel slavery, and voluntarily accept this state: “They all call themselves serfs, that is, slaves of the sovereign… This people takes more pleasure in slavery than in freedom.”

“Notes on Muscovy” was a politicized, but not anti-Russian work.

At the origins of the image of the Russian bear are Herberstein’s impressions of a trip to Moscow in the winter of 1526:

“That year the cold was so great that a great many riders, who they call gonecz, were found frozen in their carts. … In addition, many vagabonds were found dead on the roads, who in those parts usually lead bears trained to dance. Moreover, the bears themselves, driven by hunger, left the forests, ran everywhere in the neighboring villages and broke into houses; At the sight of them, the peasants fled in a crowd from their attack and died outside their homes from the cold, the most miserable death.”

As a result, the appearance of bears in winter in villages (cities) began to be perceived as a regular event and quite characteristic of Russia as a whole.

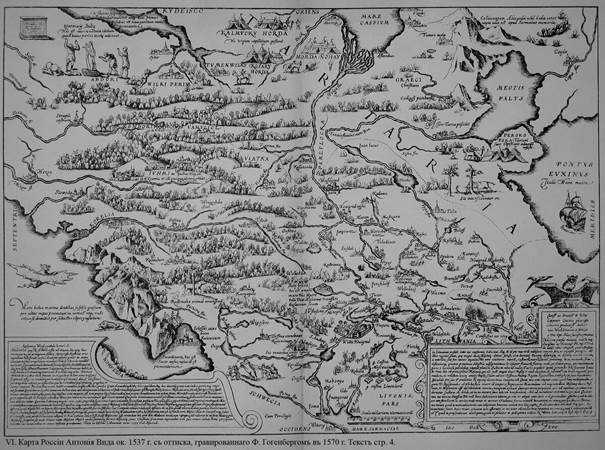

The first map of Muscovy, on which a bear is presented as a vignette, was made by the senator from Gdańsk, Antoni Wid, especially for Herberstein. Composition with bear catching in the area of Lake Onega. Wied’s map was reprinted six times as part of Münster’s Cosmographia and had a strong influence on sixteenth-century cartography.

6. Bear Map

Nevertheless, in the first half of the 16th century, Russophobia did not take root, even in England. The first Russian-English contacts were quite friendly.

The Age of Great Geographical Discoveries expanded the boundaries of the world, introduced Europeans to unknown countries and people. At the same time, it led to a certain geographical embarrassment, for in its desire to open new routes to India and China, Europe, in the person of England, unexpectedly “discovered” Russia, that is, a part of itself.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, England was one of the “offended” maritime powers. The military power of Spain barred its access to the southern seas, which washed the shores of the coveted countries, from which spices and gold flowed to Europe. Involuntarily, we had to plough the harsh northern latitudes.

In 1553, the London merchants created the Society of Merchants and Explorers for the Discovery of Countries, Lands and Islands, States and Possessions Unknown and Hitherto Unvisited by Sea.” With the share contributions, the company purchased three ships with supplies for a year and a half of sailing.

The squadron was led by Admiral Hugh Willoughby and the navigator (senior helmsman), 32-year-old Richard Chancellor, a native of Bristol, who “repeatedly showed his intelligence in practice” – it was on him that “all hope was in the successful execution of the enterprise,” explains one of the members of the expedition, Clement Adams. Willoughby and Chancellor had with them a charter from Edward VI addressed to the sovereign of the unknown Polar Empire. The charter was written in three languages (there was no Russian text); As interpreters, the English took with them two Tatars, who miraculously happened to be at the royal stable.

7. Richard Chancellor

The expedition was peaceful. The instructions of the Privy King’s Council enjoined sailors not to offend the inhabitants of the lands they met on their way, to honor their customs and manners, and even to “pretend to have the same laws and customs that are in force in the country where you come.”

Trouble awaited the sailors already off the coast of Norway. A violent storm separated the ships: Chancellor’s Edward Bonaventure was carried by the wind far to the east. After waiting in vain for two other ships for a week, Chancellor moved on at his own peril.

8.1. Chenslor’s Swim Chart

As he advanced through unknown waters, he “went so far, Adams, that he came to a place where there was no night at all, but the clear light of the sun was constantly shining over a terrible and mighty sea.” Finally, in August 1553, Chancellor’s ship with a crew of 48 entered the mouth of the Northern Dvina and anchored at the Monastery of St. Nicholas near Kholmogory (Arkhangelsk did not yet exist).

A report was sent to Moscow. The Tsar ordered the English to be brought before his eyes at once, taking care of all the expenses of travel, and ordering that horses should be given to them free of charge at the stations.

The British stayed in Moscow for several months, carefully studying the unknown country. Chancellor looked at Russia with an open mind, and in many places in his diary expresses sincere admiration for what he saw: “The country … abounds in small villages, which are so full of people that it is amazing to look at them. The whole land is well sown with grain, which the inhabitants bring to Moscow in such enormous quantities that it seems astonishing.”

Chancellor found Moscow “greater than London and its suburbs,” though “Moscow is very inelegant and planned without any order”; but “Moscow has a beautiful Kremlin, its walls are made of brick and are very high.” An Englishman to the tips of his fingernails, he rejects all national arrogance and does not skimp on praise of the Russian people: “I know of no country near us that could boast of such people”; “If the Russians knew their strength, no one would be able to compete with them.” At the same time, he noted the national isolation of Muscovites: they “learn only their own language and do not tolerate any other language in their country and in their society.” However, this reproach could have been made to any other nation at that time…

What really struck Chancellor unpleasantly (apparently as a merchant and entrepreneur) was the economic despotism of the tsar’s power: with undisguised horror he writes that the tsar has the right to deprive his subjects of land and other property; A Russian cannot say, as the common people in England do, “If we have anything, it is from God and my own”; in Russia everything belongs to “God and the sovereign’s mercy.”

But (and this is surprising) Chancellor spoke with approval of the Russian legal proceedings, though only in one respect: the Russians do not have “lawyers-specialists who would conduct the case in the courts”, that is, corrupt hook-lawyers. “Everyone conducts his own business and complaints, and answers are submitted in writing, contrary to the English order.” Subjects have the right to submit a petition directly to the sovereign himself, who judges with “remarkable impartiality.” However, the result is the same as in the English courts: “amazing abuses take place, and the Grand Duke is deceived a lot.”

Clement Adams, in turn, noted the humanity of the Russian court: “They don’t hang people for the first guilt, as we do…”

According to the totality of observations, good and bad, Chancellor’s conclusion about the Russian people was as follows: “In my opinion, there is no other people under the sun who would lead such a harsh life.”

Chancellor brought back to London only a charter addressed to Edward VI, in which Ivan promised that English merchants “will have their fairs freely throughout the entire territory of our states” – such a privilege of duty-free trade was not enjoyed by either Hanseatic or Dutch merchants.

The beginning of trade with England was mutually beneficial. Russia, which soon went to war with Livonia, received from the British everything necessary for the army: gunpowder, armor, sulphur, saltpeter, copper, tin, lead, and so on. In turn, Russian timber and hemp helped England to withstand a naval battle with Spain. Thirty years later, the victor of the Invincible Armada, Admiral Francis Drake, asked the British ambassador in Moscow to thank the son of the Terrible, Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich, for the excellent equipment of his ships, which made it possible to defend the independence of England.

Therefore, Russophobia in England in the 16th century took root with difficulty.

You can mention the person whose opinion is put in the title of the lecture. More precisely, it is a generalizing conclusion from his notes.

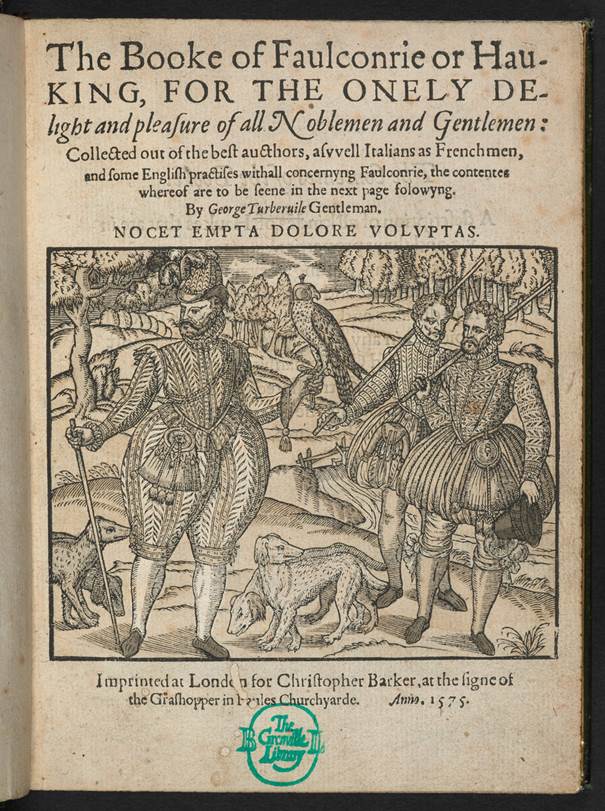

In June 1568, the ship “Harry” departed from the English shores, on board of which was the royal embassy to the distant “Muscovy” of Sir Thomas Randolph. In the ambassador’s retinue, which, as Randolph wrote, consisted of half gentlemen eager to see the world, the ambassador’s secretary was the young poet George Thurberville, the future author of three epistles in verse addressed from Russia to friends in England.

8.2. Thurberville

The embassy lasted a year, of which more than half a year was spent in painful anticipation of royal audiences in conditions resembling house arrest; it took about three months to stay in the Russian North, the rest of the time was spent on the road. The circumstances of life in Russia explain the hostile tone in the author’s description of the country and people. The negative attitude towards the environment due to the harsh meeting of Randolph and his companions in Russia was exacerbated by Thurberville’s absence of “… domestic interest in Russia… His journey was a forced break from writing, a hindrance he undertook in the hope of saving money and paying off his debts in a risky venture.

But, as his poems show, nothing came of this venture – the snob, who may have indulged in gambling with enthusiasm, and above all grains, was lost to smithereens… He took out all his grief on the country that turned out to be so inhospitable for the failed businessman.

8.3. The Book of Thurberville

In Thurberville’s view, all Russians are “idolaters”: “… After all, all their chief gods are made by hands and adzes…”

Hence Thurberville’s extremely tendentious conclusion that morality and decency cannot exist in a people who do not know the “true” (from the point of view of the representative of the Anglican Church) God and His precept.

This thesis serves as a key to the treatment of another theme in the epistles – the manners, customs and foundations of Russian society. The author accuses all Russians of a penchant for vice, ignorance, rudeness, and so on.

Why did foreigners see Russia as a “barbaric” country? There were also objective prerequisites.

The Muscovite state, which claimed to be the sole representative and defender of universal Orthodoxy, nevertheless never confined itself to a narrow national and religious framework. From the end of the 15th century, the Moscow throne was surrounded by a huge number of foreigners, mainly Lithuanians and Tatars. Historians have calculated that among the 900 most ancient noble families of Russia, the Great Russians make up only one-third, while 300 families are natives of Lithuania, and the other 300 are from the Tatar lands.

9.1. Muscovite state under Ivan the Terrible

In 1552, Kazan became part of Russia. A few years later, in 1555, the same fate befell the Astrakhan Khanate. For the first time in its history, Orthodox Russia acquired Muslim subjects.

In addition to the Kazan and Astrakhan “tsars” and “tsareviches” (i.e. khans and their sons), the Moscow sovereign received many mirzas, uhlans, and beks, each of whom brought with him a crowd of relatives and servants.

With Russia’s access to the mouth of the Volga to Moscow, Nogai, Circassian, Kabardian, Adyghe and other North Caucasian princelings and mirzas also became frequent. Many of them settled in Russian lands, like their Kazan brethren. By the way, this was facilitated by the fact that Ivan the Terrible married for the second time to the Circassian princess Kuchenya, who received the name Maria after baptism.

To Western Europeans, Moscow seemed to be an Asian city not only because of its unusual architecture and buildings (Napoleon: St. Basil’s Cathedral is “this mosque”), but also because of the number of Muslims living in it.

9.2. The Feast

An English traveler who visited Moscow in 1557 and was invited to a royal feast noted that the Tsar himself sat at the first table with his sons and the Kazan tsars, at the second – Metropolitan Macarius with the Orthodox clergy, and the third table was entirely reserved for the Circassian princes. In addition, two thousand noble Tatars were feasting in other chambers!

In the sovereign’s service, they were given not the last place. For example, Kazan tsars and princes (Kasimov Khan, Genghisid ShakhAli (Shigaley) more than once led Russian armies in the Livonian War. And by the way, there was no case when the Tatars betrayed the Moscow Tsar in the Russian service.

It can be said that at this stage, the ideologists of Russophobia were already aware of the Eurasian nature of the emerging Russian Empire. From the second half of the 16th century, Russians were different for Europe.

9.3. Livonian War

For Russophobia to assert itself in European culture, a large-scale event was required, namely a direct and prolonged military clash. Such was the 25-year Livonian War – in fact, the first such large-scale confrontation between Russia and the West (1558-1583). The war with Livonia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania escalated into a war with Poland, Sweden and Denmark, but it was the Polish nobility that played the main role in its information support and ideological justification in the West.

In the West, it was declared that Russia’s goal in the Livonian War was “the final destruction and devastation of the entire Christian world.” The slogan of Europe’s “Holy War” against Russia was put forward. At that time, a developed technology of psychological warfare was created. Printing was widely used and the genre of “flying leaflets” (leaflets) was invented.

To create a black image of Russians in the sheets, all the artistic means of describing evil in the understanding of that era were used.

Directly or indirectly, Russians were represented through the images of the Old Testament. The salvation of Livonia was compared to Israel’s deliverance from Pharaoh. It was claimed that the Russians were the legendary biblical people of Mosokh, whose invasion was associated with predictions of the end of the world.

Another theme is the “Asian” nature of the Russians. In depicting the atrocities of the Muscovites, the same epithets and metaphors were used as in the description of the Turks, and they were depicted in the same way.

Special mention should be made of the black myth of Ivan the Terrible, which has been created since the 16th century. He was consistently defined as a tyrant, a cruel and merciless torturer, so that the word “tyrant” became a byword for all rulers of Russia in general. The scale of this myth and its ideological application is such that it has been the nerve of Russian history since the sixteenth century to the present day: Russia has always been ruled by tyrants. Its main features are: multiple exaggerations of the victims and colorful descriptions of personal brutality and atrocities.

9.4. Caricature of Ivan the Terrible

The exposition of the “myth of the Terrible” often ended with plans for military intervention in Muscovy. The first to propose the “Final Solution to the Russian Question” was the former oprichnik Heinrich Staden. In presenting to the Emperor the “Plan for the Conversion of Muscovy into an Imperial Province,” he focused on the “cruel and terrible tyranny of the Grand Duke,” suggesting that the accession “to the greatest and highest glory and riches, and to all Christianity, of which you are, Your Roman-Caesar Majesty, has gone … for the benefit and edification.” Staden defined the result of the “civilizing mission” as follows: “Monasteries and churches must be closed. Towns and villages must become the free prey of the warriors.”

But the main role in the spread of Russophobic views and ideas still belonged to the Poles.

By the 17th century, the Poles had sharply separated Russia from Europe, defending the idea of its Asianness in numerous journalistic and historical works. Interestingly, earlier on European maps of Europe, the Moscow Principality was usually designated as one of the European countries, but from the end of the 16th century, the border of Europe along the eastern borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth appeared, followed by Asia, the aggregate of Tartary.

10. Great Tartary

Orientalization dictated an active position in relation to the “East”: it had to be cultivated, brought order and enlightenment. In the era of the Counter-Reformation, which began in Poland just after the end of the Livonian War, Catholic messianism was now transformed into a state ideology.

At that time, the concept of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as an “Outpost of Christianity” in the East of Europe was formed. And if in relation to Sweden and Turkey it was expressed only in military clashes, then in relation to the Russian space, Catholic expansion took the form of a church union, a state ban on the Orthodox faith, and attempts to install a Uniate patriarch in occupied Moscow.

In the propaganda literature of the early 17th century, the conquest of Moscow was also supported by the argument of the just punishment that God inflicts through the Poles on the schismatic Muscovites: this is how Y.D. Podgoretsky described the Moscow war. The Poles proved to be an instrument of God’s punishment, and the resistance of the Muscovites was seen as an insult to God himself and therefore an inconceivable audacity.

Thus, by the beginning of the 17th century, the Polish colonial-annexation ideology in relation to the Muscovite state had been developed. In his writings, Pavel Palczowski draws a parallel between the Muscovites and the Indians in America: just as the Spanish conquistadors subjugate these barbarian peoples, so the Poles in the East subjugate the Russians. The Russians are the Indians of the East for the “Polish hidalgos”. This analogy corresponded to an important noble virtue – “expansion of the fatherland”.

The civilizational mission of the Polish nobility in relation to the Slavs turned into a radical program of their enslavement by the “people of masters” (“naród panów”). This attitude was described most vividly by Stanislav Nemoevsky in his notes on the Muscovite War of 1606-1608, in which the “Muscovites” are called “probably the lowest people in the world.” Russia was seen as a space for assimilation and subordination, and Russian culture as unworthy of existence.

After the Livonian War and the Time of Troubles, Russophobia was nourished by clichés and myths for a century and a half. When, in 1633, in the book of Edo Noichuz, it was written about the Russians that “this tribe was born in slavery, accustomed to the yoke and does not tolerate freedom,” this formulation was already banal and almost no one questioned it. The most popular description of Russia was made by the German traveler and scholar Adam Olearius in 1647 and was constantly reprinted in almost all Western languages. Olearius wrote: “Observing the spirit, manners and way of life of the Russians, you will certainly rank them among the barbarians.” He also warned future civilizers that Russians were “fit only for slavery” and should be “driven to work with whips and clubs.”

But under Peter the Great, Russia began to become Europeanized. And what is it?

Each new clash between Russia and the West has intensified European Russophobia. The “War of Pamphlets” was also actively waged during the Great Northern War. The Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1728 still characterizes Russia as a European country, but at the same time reports that despots rule there, and the Russian people are cruel, vile, and savage. Montesquieu writes that “the people there consist only of slaves,” Rousseau wrote that “the Russians will never become a truly civilized nation.” Voltaire, in his History of Charles XII, describes pre-Petrine Russia in the same derogatory epithets: “Muscovy, or Russia… remained almost unknown in Europe until Tsar Peter came to the throne. The Muscovites were less civilized than the inhabitants of Mexico when Cortés discovered it. Born slaves of rulers as barbarous as themselves, they languished in ignorance, knowing neither arts nor crafts, and not understanding their usefulness.”

Even the virtues of the Russians were due to their reprehensible differences from civilized Westerners.

Denis Diderot wrote a section on Russia for Abbé Raynal’s large book The History of the Two Indies (1780). He explains why the Russian soldier is so brave: “Slavery, which inspired him with contempt for life, is combined with superstition, which inspired him with contempt for death.” Amazingly, this formula of the 18th century worked almost without variations for 200 years and was literally repeated by Hitler’s generals.

The policy of containing and isolating Russia from Europe was formulated by Napoleon. According to the memoirs of A. de Caulaincourt, during the invasion of Russia on June 30, 1812 in the captured Vilna, Napoleon declared: “I have come to put an end once and for all to the colossus of the northern barbarians… It is necessary to throw them into their ice, so that for 25 years they will not interfere in the affairs of civilized Europe. Civilization rejects these inhabitants of the north. Europe must be able to do without them.” At present, this idea is expressed in a milder form, which, however, does not change its inner content.

The image of Russia as the main enemy of freedoms in Europe became especially relevant during the Polish uprising of 1830-1831, and even more so after it, when the Polish Great Emigration in Europe was able to turn almost all public opinion to the defense of Poland. Thousands of educated families, who were the bearers of this ideology, dispersed to all countries of the West. The Polish people were presented as the bearers of the ideas of freedom and progress, while Russia was the “strangler” of all freedoms and the embodiment of reaction.

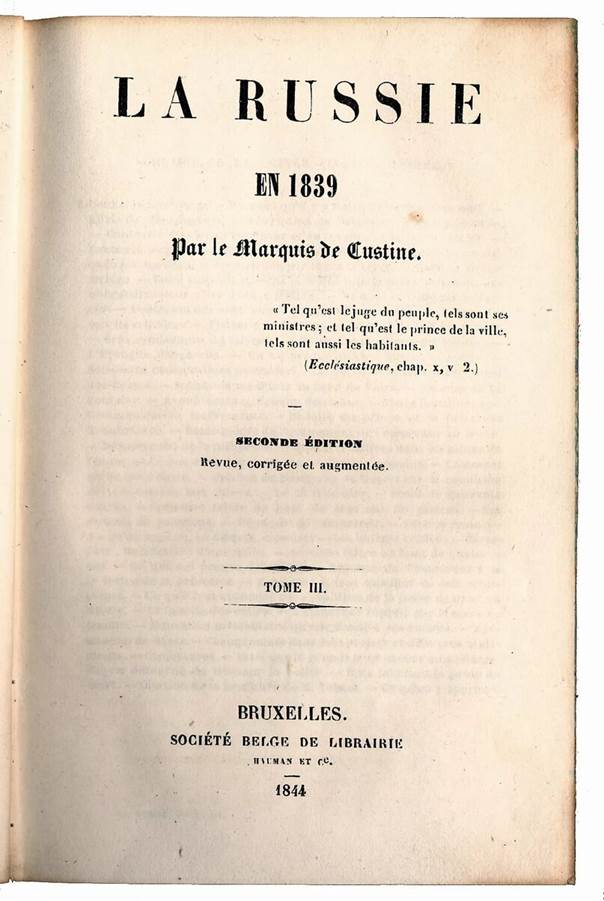

11. Marquis de Custine

The name of the Marquis Astolphe de Custine is known even to those who have not read a single line written by him. He wrote several historical and journalistic works, including his travels in England, Scotland, Switzerland, Italy (1811-1822), Spain (1833), and Russia (1839). He became famous for his book Russia in 1839, a narrative about a journey made in the summer of 1839, published in May 1843. The author himself, perhaps, was not inclined to consider “Russia” as his main work; Meanwhile, it was this book, which was immediately translated into English and German and brought him European fame.

His grandfather, a general who commanded the Army of the Rhine in 1792, and his father were guillotined during the Jacobin Terror.

Custine was a very wealthy aristocrat, his social circle included many representatives of the European elite. The Marquis traveled a lot to the countries of Europe, wrote travel notes to them, was engaged in literary activities: several novels and plays came out from his pen. Custine is also a staunch monarchist.

In his time, Custine enjoyed considerable fame; among the admirers of his talent was such a sophisticated connoisseur as Balzac, who, having read Custine’s book on Spain, convinced its author that “by dedicating such a work to each of the European countries, he will create a collection, unique in its kind and truly priceless.”

The reason for Custine’s trip to Russia was given by a young Polish count, Ignacy Gurovsky, who had fallen out of favor with the Russian Tsar and had come to Paris to seek protection. Custine collected letters of introduction to Nicholas I from his influential friends and went to Russia, formally to plead for his Polish friend.

In Russia, Custine’s book was immediately banned. The first complete Russian translation of both volumes under the author’s title “Russia in 1839” was published in 1996.

Meanwhile, the full text of “Russia in 1839” and its abridged versions are works of different genres. The authors of the “digests”, choosing from Custine the most biting, the most “anti-Russian” passages, turned his book into a pamphlet. Custine, on the other hand, wrote something quite different: an autobiographical book, an account of his own (the autobiographical moment is extremely important here) journey through Russia in the form of letters to a friend.

So, one of the sources of Custine’s longevity is that it not only describes a trip to real Russia, but also carries out a kind of judgment on the idea, the myth of Russia, supposedly designed to save old Europe from a democratic revolution.

In Russia in 1839, the perception of Russia as a country of “barbarians” and slaves, universal fear and “bureaucratic tyranny,” the book provoked a flood of official refutations. The attitude of the Russian intelligentsia towards it was contradictory. Zhukovsky called Custine a dog, but he could not help but admit that most of what he wrote was true.

Custine’s book touches on so many sore spots in the national self-esteem that the perception of it by many people is still distinguished by a fervor that is usually evoked only by the most topical journalism: Custine is offended, scolded, branded for “Russophobia,” and so on. Meanwhile, the formula coined in passing by the Moscow postmaster A.Y. Bulgakov: “And the devil knows what his true conclusion is, now we are the first people in the world, now we are the most vile!” remarkably covers the entire range of Custine’s impressions of Russia.

Russia is described in extremely dark terms. He attributes hypocrisy and only imitation of the European way of life to the Russian nobility. In Russia, the Marquis finds it difficult to breathe—everywhere he feels the tyranny emanating from the Tsar. Hence the slavish character of the Russians, who also live as slaves imprisoned in a narrow framework of obedience.

In Russia, the principle of pyramidal violence applies: the tsar has absolute power over the nobility and officials, who in turn are also complete masters over the lives of their subjects, and so on up to the serfs, who unleash their cruelty on each other and on the family. In the opposite direction of the pyramid, ingratiation and hypocrisy with superiors operate. According to Custine, Russians, disliking European culture, imitate it in order to become a powerful nation with its help. And only the simple peasants who live freely in the provinces are praised by Custine for their simple and freedom-loving character.

Criticizing the tyranny and autocracy of the tsar as an institution of Russian rule, Custine nevertheless writes that the only person in Russia with whom he was pleased to communicate and who was sufficiently educated and exalted in soul was Nicholas I.

Here are excerpts from his writing:

“The more I get to know Russia, the more I understand why the Emperor forbids Russians to travel and makes it difficult for foreigners to enter Russia. The Russian order would not have endured twenty years of free relations between Russia and Western Europe.

.. I wonder whether the character of the people was created by the autocracy, or whether the autocracy created the Russian character, and… I can’t find the answer…

Russia is camp discipline instead of a state system, it is a state of siege elevated to the rank of a normal state of society.

I do not reproach the Russians for being what they are, I condemn their pretensions to appear like us. They are still uneducated, but this condition at least gives hope for the best; Worse still, they are constantly consumed by the desire to imitate other nations, and they imitate just like monkeys, dumbing down the object of imitation.

What is the Russian nobility doing? It worships its king, and becomes an accomplice in all the crimes of the supreme power, in order to torture the people itself, until the god whom this ruling class serves, and whom it itself has created, leaves the lash in its hands. Is this the role that Providence has assigned to the nobility in the state-building of the world’s largest country? In the history of Russia, no one but the sovereign has fulfilled what was his duty, his direct mission, neither the nobility nor the clergy. A people under the yoke is always yoked: tyranny is the creation of a people who obey it. And in less than fifty years, either the civilized world will again fall under the yoke of the barbarians, or a revolution will break out in Russia, far more terrible than the one the consequences of which Western Europe is still feeling.

And here is the famous:

“As vast as this empire is, it is nothing but a prison, the key of which is kept by the emperor.”

Astolphe de Custine called Nicholas I “the jailer of one third of the globe.”

11.2. The Book of Custine

In a 1987 annotation to the American edition of La Russy, the American politician Z. Brzezinski: “Not a single Sovietologist has yet added anything to de Custine’s insights regarding the Russian character and the Byzantine nature of the Russian political system.”

The Polish uprising of 1863-1864 provoked new emigration and the creation of entire intellectual centers focused mainly on confrontation with Russia (as, for example, in Lviv, Austria at that time, where a significant part of Polish refugees moved). At the same time, the theory of Ukraine as not Russia emerged. The first to consider that Ukrainians are not Russians was the Polish scientist Count Jan Potocki in 1796. A little later, another Pole, Count Czacki, came up with the idea that the Ukrainians were descended from the Slavic tribe of the Ukies, who supposedly came from Asia (the Ukrians on the Ukie in Slavic Pomerania). Today, in Ukraine, alas, there is not such a thing.

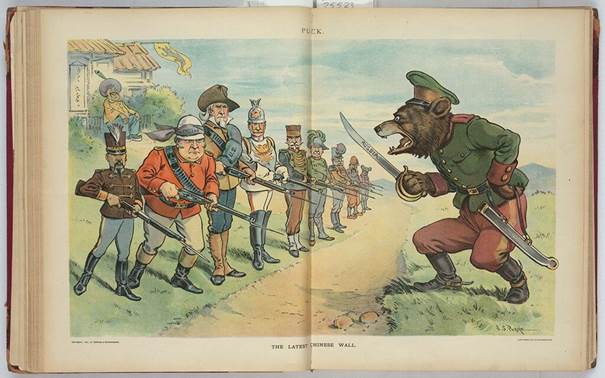

The United Kingdom has become one of the main conductors of Russophobic ideas. British interests clashed with Russians in almost the whole of Asia: in Central Asia, in the Caucasus, and in the Far East. Throughout the nineteenth century, English society lived in an artificially inflated fear of the expectation that Russia was about to carry out a new southern campaign and seize British India.

Britain’s information war against Russia has used the language of satirical images to a much greater extent than previous ones. Through them, the image of Russia as a bear began to be actively planted in European public opinion.

In the West, the image of a bear has a completely different symbolism than in our country. Relying on the Bible, where the bear is always shown from the bad side, and picking up on St. Augustine’s phrase “ursus est diabolus”, “the bear is the devil”, the Church Fathers and Christian writers of the Carolingian era assign it a place in the bestiary of Satan; moreover, if we are to take their word for it, the Devil often takes the form of a bear, in which he comes to frighten and torment sinners. Most of the authors… The vices of the bear are constantly emphasized: cruelty, malice, lustfulness, impurity, gluttony, laziness, anger. … From the thirteenth century onwards, the bear even became a prominent figure in the bestiary of the Seven Deadly Sins, for it is associated with at least four of them: anger (ira), lust (luxuria), idleness (acedia), and gluttony (gula).”

11.3. Russia: Bear: Cartoon of the Crimean War

Characterizing Russia as a bear is still the most common method of discrediting it in Western journalism. Despite the ingenious idea of the emblem of the 1980 Olympics.

Throughout the 19th century, German Russophobia became more and more important, and by the middle of the century it had acquired its racist forms.

In relation to Russia, to the Russians, paranoid notes have already begun to sound. The great neighbor to the east, which had contributed so much to the creation of a united Germany, was looked upon with hatred and fear. The fundamental characteristics of the Russian people were backwardness, savagery, despotism, and inability to create history. At the same time, German historians extolled the role of the German element in Russian history, from the notorious Varangians to the Baltic Germans who filled Russian chancelleries, ministries, military headquarters, and universities.

The most odious exponent of such views was the Pan-Germanist Victor Hoen, who asserted in his book De moribus Ruthenorum (1892) that the Russians “have no traditions, roots, or culture on which to rely,” “everything they have has been imported from abroad”; They themselves are not able to put two and two together, their souls are “permeated with age-old despotism,” so “without any loss to mankind they can be excluded from the list of civilized peoples.” These monstrous follies found connoisseurs in all strata of German society, and even the leader of the Social Democratic faction of the Reichstag, August Bebel, repeatedly said that, if necessary, he would take a gun on his shoulder and go to war to defend his homeland against Russian despotism.

Russophobic ideology is very expressively manifested in the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Hatred of the Russians was combined with racial contempt for the Slavs in general. They were seen as organic opponents of progress: “The Slavic barbarians are natural counter-revolutionaries, special enemies of democracy” (Marx).

It is noteworthy that Marx was a supporter of the racial constructions of the Pole Francisk Duczynski. He is the author of his own version of the Turanian theory (about the Asian origin of the Russian people). Marx writes: “Lapinsky’s dogma that the Great Russians are not Slavs is defended by Mr. Dukhinsky (from Kiev, professor in Paris) in the most serious manner from the linguistic, historical, ethnographic, etc. points of view, he asserts that the real Muscovites, i.e., the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Moscow, are for the most part Mongols or Finns, etc., as well as the parts of Russia farther to the east and its southeastern parts. The name Rus was usurped by the Muscovites. They are not Slavs and do not belong to the Indo-Germanic race at all, they are intrus (foreigners) who are to be driven back beyond the Dnieper, etc.”

In Revelations of the Diplomatic History of the Eighteenth Century, Marx writes: “Muscovy was brought up and brought up in the terrible and vile school of Mongol slavery. It was only strengthened by becoming a virtuoso in the art of slavery. Subsequently, Peter the Great combined the political skill of the Mongol slave with the proud aspirations of the Mongol sovereign, to whom Genghis Khan bequeathed to carry out his plan for the conquest of the world. And from this conclusions are drawn: “In the war with Russia, the motives of the people who shoot at the Russians are completely indifferent, whether the motives are black, red, gold or revolutionary… Hatred of the Russians was, and still is, the first revolutionary passion.”

Engels was no less harsh on the Slavs. In 1849 he wrote in the Neue Rheinische: “The next world war will wipe off the face of the earth not only reactionary classes and dynasties, but whole reactionary peoples. Europe has only one alternative: either to submit to the yoke of the Slavs, or to completely destroy the center of this hostile force, Russia.

“The Slavic peoples of Europe are miserable, dying nations, doomed to destruction. At its core, this process is profoundly progressive. The primitive Slavs, who have contributed nothing to world culture, will be absorbed into the advanced civilized Germanic race. Any attempt to revive Slavism emanating from Asiatic Russia is “unscientific” and “anti-historical.” In the final analysis, the Germans and the Germanized Jews must own not only the Slavic regions of Europe, but also Constantinople” (Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany).

“What is needed is a ruthless life-and-death struggle against the Slavs, who are treacherous to the revolution, a war of extermination and unrestrained terror. Europe has only one alternative: either to submit to the yoke of the Slavs, or to completely destroy the center of this hostile force, Russia.

These epithets and arguments can be considered typical of Western thought about Russia. Marx’s words that a European newspaper, in order to be considered liberal, “have only to show hatred of Russians in time” still sound contemporary.

On the basis of all this, it would be reasonable to accept that for many centuries the ruling elite of the West has developed and perfected a stable idea of Russia as a different, alien and fraught threat to civilization. There is no indication that this submission has been revised.

At the same time, self-hatred develops to the highest intensity, to religion.

Journalist Tim Kirby even thinks it is possible to talk about the existence of a special “religion of self-hatred” in Russia.

Boris Groys (philosopher, Slavic scholar): “Russia has responded to Western expansionism with a strategy of self-occupation, self-colonization, and self-Europeanization.”

That is, hatred of one’s own is directly related to and is directly conditioned by the opposite attitude towards the other, which can be recognized as a very peculiar psychological state.