“Potemkin Villages” – How the Myth Was Created

Two successful wars with Turkey made Russia the owner of Crimea and Novorossiya, a wide strip of land along the northern coast of the Black Sea.

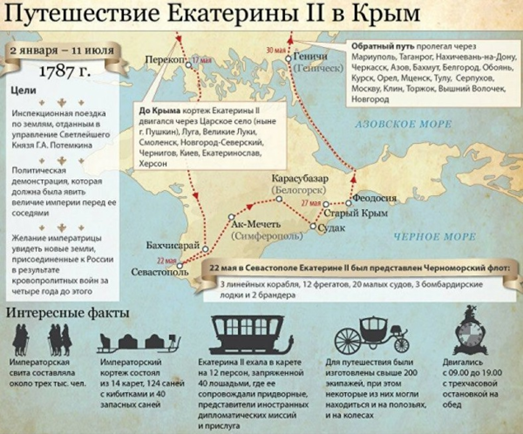

In 1787, the Empress wished to receive, so to speak, a visual report on the expenditure of the huge funds allocated to His Serene Highness Prince Potemkin for the improvement of this region. On January 18, she left St. Petersburg, accompanied by foreign ambassadors and almost the entire court. The tsar’s train consisted of 14 carriages and 124 sleighs with 40 spare ones. At each station, 560 horses were waiting for him. Along the entire road, giant bonfires were stacked at short intervals, lighting the way at nightfall. In Ukraine, Catherine’s retinue was replenished by two European monarchs: the Polish king Stanisław Poniatowski and the Austrian Emperor Joseph II (who traveled incognito, under the name of “Count Falkenstein”).

Potemkin did his best. At his command, crowds of well-dressed peasants ran to the road, enthusiastically greeting the Mother Empress. And in the distance from the carriage one could see the famous “Potemkin villages” erected by His Serene Highness the Prince along the entire route of Catherine.

And so the myth was born.

One of his “fathers” can be considered the Swedish eyewitness John-Albert Ehrenström, who wrote: “By nature, the empty steppes were inhabited by Potemkin’s orders, people were inhabited, villages were visible at a great distance, but they were painted on screens; Men and herds are brought to appear for this occasion, in order to give the autocrat an advantageous idea of the wealth of this country. Everywhere you could see shops with fine silverware and expensive jewelry, but the shops were the same and were transported from one night [of Catherine II. – S.Ts.] to another.”

However, Ehrenström wrote his memoirs decades after the trip (he lived until 1847). In addition, his track record is far from the “moral image” of an impartial witness: he was a political adventurer who served his homeland and Russia, was pilloried (literally) and once almost lost his head on the scaffold after receiving a pardon at the very last moment.

However, the secretary of the Saxon envoy, G. Helbig, wrote approximately the same thing, reflecting the opinion of Emperor Joseph II: the picturesque villages were just theatrical scenery; Catherine was shown the same herd of cattle several times in a row, which was driven at night to a new place; In military stores, sacks were filled not with grain, but with sand (Brickner A. G. Potemkin, St. Petersburg, 1891, p. 101).

However, it cannot be considered that “such was the general voice.” The not at all gullible Prince de Ligne, returning from Taurida to St. Petersburg, in Tula called the stories about the scenery a ridiculous fable (from which it is clear, in particular, that the myth of the “Potemkin villages” arose directly during Catherine’s journey, and even a little earlier).

The fact that she would see painted scenery, and not long-term buildings, was told to the Tsarina in St. Petersburg by Potemkin’s envious and enemies. Talk of the indispensable hoax became even more lively in Kiev, and Catherine II listened to them quite seriously. It is no coincidence that in the diary of A. V. Khrapovitsky we find the following entry dated April 4, 1787: the Empress is eager to leave for Novorossiya as soon as possible, “despite the unpreparedness of P<nyazya> P. <Otemkin> to hold that campaign.”

What did the Empress and her magnificent retinue really see in Novorossiya? What did Potemkin show them?

His Serene Highness prepared and presented a spectacle magnificent in its variety and magnificence. Of course, it was not without the whimsical tyranny for which Potemkin was famous. Such, for example, is the story of the notorious Amazonian company. It is reported that shortly before the journey, when he was still in St. Petersburg, Potemkin, in a conversation with the Tsarina, “praised the courage of the Greeks and even their wives.” Catherine expressed doubts about this, and Potemkin promised to present evidence in the Crimea. Immediately (it was in March) a courier galloped to the Greek regiment of Balaklava, with instructions to “certainly organize an Amazonian company of armed women.” Yelena Sardanova, the wife of a company captain, was made its commander; “A hundred ladies gathered under her command.”

The Balaklava Amazons came up with a masquerade outfit: “skirts made of crimson velvet, trimmed with gold galloon and gold fringe, jackets of green velvet, also trimmed with gold galloon; on their heads are turbans of white haze, embroidered with gold and sequins, with white ostrich feathers.” They were even armed: they were given a rifle and three blank cartridges each. Not far from Balaklava, the Empress, accompanied by Joseph II, made a review of the Amazons. “There was an avenue of laurel trees, strewn with lemons and oranges,” etc.

Illuminations and fireworks were a magnificent spectacle. In Kaniv on the evening of May 7, when the Polish King Stanisław August was leaving, “he was saluted from the imperial yacht with cannons from the flotilla, as in the morning. The illumination of the obelisk with the monogram of the Empress was very successful, as was the girandole with a bouquet of four thousand rockets, and the fiery mountain, which seemed to be lava” (memoirs of one of the court ladies of the Polish king).

The fireworks in Sevastopol made a particularly great impression. Prince Karl-Heinrich of Nassau-Siegen, who was in the Russian service, describes the enthusiastic reaction of “Count Falkenstein”: “The Emperor says that he has never seen anything like it. The sheaf consisted of 20,000 large rockets. The Emperor called for fireworks and asked him how many rockets there were, “in case,” he said, “so that he would know what to order if he had to burn a good firework.” I saw a repetition of the illumination on the day of the fireworks; All the mountains were crowned with the monograms of the Empress, made up of 55 thousand bowls. The gardens were also illuminated; I’ve never seen such magnificence!” Equally luxurious and wasteful illuminations were in Bakhchisaray and other cities.

Let us leave aside the question of the millions of government rubles that have been put into the air. Let’s understand the main thing: Potemkin did decorate cities and villages, but he never hid the fact that these were decorations. Dozens of descriptions of the journey through Novorossiya and Taurida have been preserved. In none of these descriptions, made in the wake of the events, is there any hint of “Potemkin villages”, although the decoration is mentioned repeatedly. Here is a typical example from the notes of Count Ségur: “Towns, villages, manors, and sometimes simple huts were so decorated with flowers, painted decorations and triumphal gates that their appearance deceived the eye, and they seemed like some marvelous cities, magically created castles, magnificent gardens.”

Potemkin’s constructions were not intended to throw dust in the eyes or deceive the Empress with the appearance of false prosperity. Artistic decorations were an integral part of the manor culture of that time. In this way, Potemkin sought to revive the desert spaces of the South Russian steppes, to make their appearance pleasing to the eyes of the Empress, and at the same time unfolded in front of her a grandiose model of the future Novorossiya.

Everyone knew that Novorossiya, conquered from Turkey, was a desert steppe, with no cities, no roads, and almost no settled population. Potemkin’s goal was to demonstrate that with Russian power came European civilization to this vast region.

“I confess that I was astonished at all that I saw,” wrote the Comte de Ludolphe, “it seemed to me that I saw the magic wand of the fairy, which everywhere creates palaces and cities. Prince Potemkin’s wand is powerful, but it weighs heavily on Russia… You no doubt think, my friend, that Kherson is a desert, that we live underground; Disbelieve. I formed such a bad idea of this city, especially at the thought that eight years ago there was no habitation here, that I was utterly astonished at all that I saw. Prince Potemkin… I threw seven million rubles for the establishment of a city here.” And then there are the praises of the “Kremlin”, the houses, the layout of the streets, the “garden of the Empress” (“it has 80 thousand fruit trees of all kinds that flourish”, the palace built for the Empress, the shipyard, etc.

The foundation of Yekaterinoslav became a symbol of civilizing efforts. This happened the next day after the arrival of Emperor Joseph II. In particular, the giant statue of Catherine did not have time to arrive from Berlin. But the grandiosity of Potemkin’s plans was already striking. After a prayer service was held in the field church (i.e., a tent spread out on the bank of the Dnieper), the two monarchs laid the first stone in the foundation of the Ekaterinoslav Cathedral.

According to the project, it was supposed to resemble the Cathedral of St. Peter. St. Peter’s Church in Rome. There are reliable stories that Potemkin ordered the architect to surpass this main shrine of the Catholic world, “to let it run by a yard longer than the cathedral in Rome.” Alas, the grandiose construction was never realized: only the foundation was erected, which cost seventy thousand rubles; Subsequently, when Ekaterinoslav turned from a project into a real city, the church was still completed, but it was so modest that the foundation became its fence.

But in this case, it is not the reality that is more interesting, but Potemkin’s idea and plans, which were grandiose to the point of fantasy. Ekaterinoslav was supposed to be the capital of Novorossiya. Everything was foreseen – even the music academy, which was supposed to be headed by the famous Sarti, was not forgotten. If it is permissible to speak of “Potemkin villages”, then one of them was Ekaterinoslav, a mirage city on the Dnieper bank.

Ekaterinoslav was called upon to become a rival of St. Petersburg. This is quite a Russian tradition; To understand it, let’s cite a few historical references.

Since the times of ancient Russia, the idea of succession and state development has been symbolized by the “renewal” of capitals and patronal churches. Andriy Bogolyubsky contrasted Kiev with Vladimir with its Golden Gates and new churches. Ivan the Terrible contrasts Moscow with Vologda with the Assumption Cathedral (also called the Cathedral of St. Sophia) on the model of the Moscow Cathedral, which, in turn, through the Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir, is successively connected with the Kiev Sophia.

During the reign of Peter the Great, the role of Vologda was played by St. Petersburg. According to Feofan Prokopovich, it personifies the new, “golden” Russia, which is seen as a counterbalance and opposition to Muscovite Russia, the “ancient” Russia.

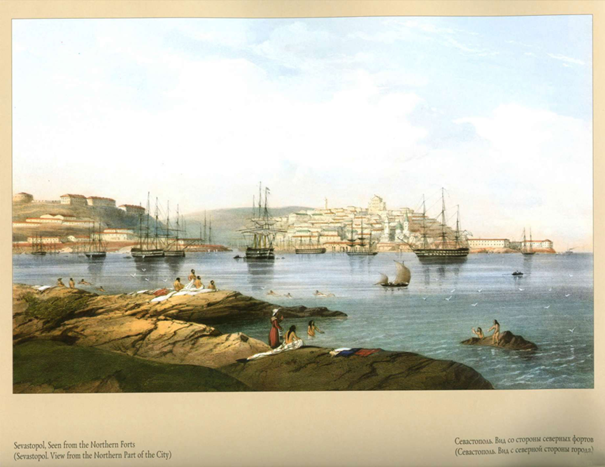

The apotheosis of the “journey to Tauris” was the visit of the Tsarina and her retinue to Sevastopol. At the ceremonial dinner in the Inkerman Palace, from the windows of which there was a magnificent view of the Sevastopol roadstead. At a sign given by Potemkin, the curtains were pulled back and the Black Sea Fleet, which was stationed in the roadstead, saluted Catherine and her guests. An eyewitness recalled: “The Emperor was amazed to see… Beautiful warships, created as if by magic… It was magnificent… Our first thought was to applaud.” On a walk, Count Ségur said to “Count Falkenstein”: “I… seem… that it was a page from the Arabian Nights, that my name was Jaffar, and that I was walking with the Caliph Haroun al-Rashid, in his usual disguise.”

As you can see, Potemkin’s scenery has fulfilled its purpose. And very soon Turkey had to be convinced that the myth of “Potemkin villages” was indeed a myth.

Materials used:

A. M. Panchenko. “Potemkin Villages” as a Cultural Myth // Russian Literature of the XVIII — Early XIX Centuries in the Socio-Cultural Context. Leningrad, 1983. S. 93-104. (XVIII century, Sat. 14).