Why did Stalin classify the results of the 1937 census?

Author: Oleg Kildyushov, Research Fellow, Centre for Fundamental Sociology, National Research University Higher School of Economics.

In the history of national statistics and demography, a special place is occupied by the All-Union Population Census, which was conducted on January 6, 1937 and coincided with the beginning of the Great Terror. Designed to confirm the pattern of rapid population growth under socialism proclaimed by the Soviet leader J. V. Stalin, the census, on the contrary, revealed a real demographic catastrophe. The Soviet authorities tried to conceal its scale by attributing the disappearance of millions of people to the intrigues of “wreckers” who had crept into the ranks of statisticians.

The main goal pursued by the communist authorities in conducting the census in 1937 was to obtain objective information about the size and structure of the country’s population, which had radically changed in comparison with the 1920s. The political importance that the Kremlin leaders attached to the forthcoming census can be appreciated by the fact that J. V. Stalin personally edited the last version of the questionnaire.

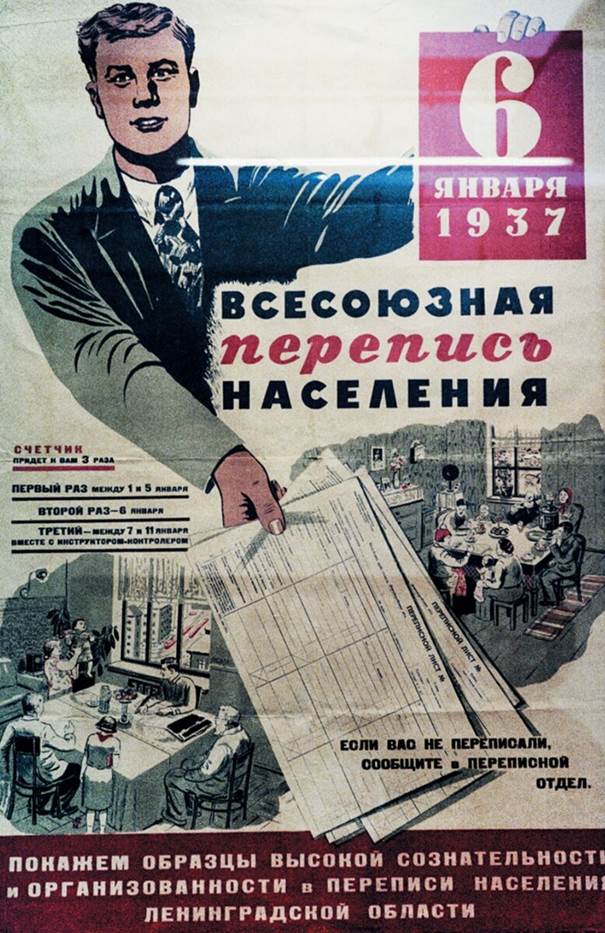

As part of the preparations, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR adopted a special appeal to the population, in which they explained the national economic significance of the census and declared that participation in it was the duty of every Soviet person. The propaganda campaign included the publication of propaganda brochures and posters, as well as awareness-raising with the population. The census was widely advertised in the Soviet press as an indisputable confirmation of the success of the country’s leadership’s policy in building socialism. In fact, it was supposed to reveal the unequivocally positive demographic results of such processes as collectivization, industrialization, and the struggle against the Church within the framework of the Cultural Revolution. “Objective” data (obtained with the help of the proven methodology of statistical science) were supposed to confirm Stalin’s thesis about the final victory of socialism in the USSR by the mid-1930s.

Propaganda poster of the Second Five-Year Plan for the Development of the National Economy of the USSR. 1933

According to the researcher of Stalinism, A. N. Medushevsky, the questions of the questionnaire were formulated in such a way that the answers to them demonstrated the absence of any social differentiation within a single Soviet society, which had finally overcome the former class division. When comparing the draft census form with its final version in J. V. Stalin’s version, it is obvious that there was an unequivocal rejection of questions that made it possible to obtain a detailed picture of the social structure (similar to the one given by the 1926 census). A differentiated study of the social composition of the population was replaced by the lapidary question of membership in a particular social group, which was immediately proclaimed an outstanding achievement of Soviet statistics and remained in the questionnaires of Soviet censuses until the very end of the USSR. According to modern demographers, Stalin’s changes to the questions carefully thought out by statisticians greatly simplified the formulations, but at the same time deprived them of certainty, eventually allowing for ambiguous interpretations.

In total, the census form consisted of 14 items, among which the most important were gender, age, nationality, native language, religion, citizenship, literacy, occupation, place of work, belonging to a social group, etc. Population growth, a key indicator of the success of any policy in modern mass society, was much lower than expected. However, not only the quantity, but also the “quality” of the inhabitants of the “country of victorious socialism” greatly disappointed the communist leaders:

More than half of the Soviet citizens declared that they were believers!

If we talk about specific figures, then the census of January 6, 1937 revealed 162,003,225 people in the country, including “special contingents”, servicemen of the Red Army and the NKVD. On the one hand, this meant an increase of 15 million people (10.2%) compared to 1926. On the other hand, the figures obtained were much lower than expected. Thus, according to the data of the current population census as of January 1, 1933, State statistics agencies estimated the population of the Soviet Union at 165.7 million people. At the beginning of 1934, the country’s population was estimated at 168 million people, which was announced by Stalin personally from the rostrum of the XVII Party Congress. And by 1937, at least 170-172 million people were expected, so based on these expected numbers, 8-10 million people “disappeared” without a trace. It should be noted here that, despite the relative stabilization of demographic processes during the years of the NEP (a relatively high birth rate with a stable mortality rate), postwar population growth began to slow down in the late 1920s, although it still exceeded the pre-revolutionary level. Nevertheless, on June 27, 1930, J. V. Stalin optimistically declared at the Sixteenth Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) that “the workers and peasants in our country live, on the whole, are not bad, the mortality rate of the population has decreased in comparison with the pre-war period by 36 per cent in general and by 42.5 per cent in the children’s line, and the annual increase in our population is more than 3 million souls. This means that every year we get an increment of the whole of Finland (General laughter in the hall.)».

Delegates to the VIII All-Union Extraordinary Congress of Soviets. In the first row, from left to right, sit N. S. Khrushchev, A. A. Zhdanov, L. M. Kaganovich, K. E. Voroshilov, I. V. Stalin, V. M. Molotov, M. I. Kalinin and M. N. Tukhachevsky. Moscow, December 1, 1936

As the historian and demographer A. G. Volkov writes, Stalin’s thesis about the specifics of demographic processes under socialism, according to which the birth rate in a socialist society should constantly grow, and the death rate should steadily decrease, eventually turned into an official dogma. The authorities believed that an annual population growth of three million was the norm of demographic development in the USSR. Meanwhile, the forced collectivization and industrialization that unfolded during the First Five-Year Plan and affected huge masses of the population inevitably led to a decrease in the rate of population growth in the early 1930s. Thus, the very practice of Stalin’s modernization called into question Stalin’s dogma about the rapid increase of population under socialism. The negative trend was also evidenced by the data on the sex-age structure of the population: if in 1926 there were 5 million more women than men, who made up 51.7% of the total population in the USSR, then in 1937 they already made up 52.7% of the population, and the gender imbalance was at the level of 8.5 million. According to the calculations of modern scientists based on the data of the 1937 census, the excess mortality of the population of the Soviet Union in the period between the two censuses (i.e., in 1926-1937) in absolute figures could be from 7.5 to 11 million people.

This is the approximate scale of the victims of collectivization and industrialization.

According to A. G. Volkov, “collectivization, dekulakization, deportation of the dekulakized, mass exodus of peasants from the countryside, the ‘unloading’ and ‘cleansing’ of the cities and the ensuing terrible famine of 1933, as well as the repressions that were becoming massive, caused a demographic catastrophe that could not but be revealed in the census data.” In a letter to Stalin and the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR V. M. Molotov in March 1937, the leadership of the Central Directorate of National Economic Accounting of the USSR State Planning Committee tried to explain such a sharp gap between the expected and the results obtained: first, it estimated 1% of population growth per year as exceeding the indicators of the advanced capitalist countries; secondly, the unsatisfactory state of the current registration of the population, which provoked inflated expectations, was pointed out; Thirdly, there was talk of “very active attempts by hostile class elements” to interfere with the census, etc. No less negative reaction from the Soviet leadership than the general “underestimated” figure of the population was caused by the answers of the Soviet people to the question about their attitude to religion: 55.3 million (!) people over the age of 16 (56.7%) called themselves believers. Almost 80% of all believers were Christians; At the same time, 75% of the population indicated belonging to Orthodoxy, and 0.8% of all believers identified themselves as Catholics and Lutherans.

Thus, the results of the census, instead of demonstrating the successful policy of the Communists to eradicate religious consciousness, showed its complete failure.

It is noteworthy that it was Stalin who included a question on religion in the census form, apparently in the hope of confirming his thesis about the “complete atheism of the population.” It is also interesting how the believers themselves behaved. According to the well-known historian and demographer V. B. Zhiromskaya, most of them did not hide their beliefs. As an illustration, the researcher cites typical answers recorded by counters: “No matter how many questions you ask us about religion, If you can’t convince us, write ‘believer‘ or “Even though they say that all believers will be fired from the construction site, but write us believers.” In one case, all seven women who lived in the same dormitory room of the Promodezhda factory (Perm) signed up as believers. A similar case was recorded in another dormitory, where twelve women between the ages of 17 and 29 stated that that they are believers. In some districts, entire collective farms were registered as believers. Under the influence of rumors and fears, people sometimes “rewrote” themselves as believers and non-believers several times. However, such cases were rare. For some, it was the first time they had to make up their minds. For example, the following answer is typical: “Who knows whether I believe it or not, I don’t know, but there is something in the soul that is above us, there is something, some kind of power; Though I have not prayed to God for a long time, yet write, ‘Believer.'” Others solved the issue quite differently: “… If I work at a construction site, then I am an unbeliever.”

Apparently, the real percentage of believers was even higher, since some respondents were afraid to admit their religiosity for fear of sanctions from the authorities. In addition, with a high degree of probability, it can be assumed that those who did not answer the question about religion were mostly believers. In total, 80% of respondents answered this question. About 1 million people referred to the fact that they were “responsible only to God”; The answer was often that “God knows whether I am a believer or not.” Of particular interest in the context of the Stalinist Cultural Revolution are the census data on the literacy of believers: among the men of the Christian faith, the majority were literate. For example, this figure was 78.9% for Orthodox Christians, 77.3% for Catholics, and 90.6% for Protestants. Needless to say, such figures unequivocally refuted the thesis of the atheistic propaganda of the Bolsheviks that the spread of literacy automatically leads to the rejection of religion! It is very likely that this ideologically dangerous moment was another reason for the classification of the census results.

In any case, on September 23, 1937, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR decided:

“In view of the fact that the All-Union Population Census of January 6, 1937, was conducted by the Central Department of National Economic Accounting of the State Planning Committee of the USSR with gross violation of the elementary foundations of statistical science, as well as in violation of the instructions approved by the government, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR decides:

1. To recognize the organization of the census as unsatisfactory and the census materials themselves as defective.

2. To oblige the Central Department of National Economic Accounting of the State Planning Committee of the USSR to conduct the All-Union Population Census in January 1939.

Propaganda poster “All-Union Population Census”. 1937

In order to get out of this uncomfortable situation, the political leadership of the USSR, headed by Stalin, ordered the NKVD to launch a campaign to expose the “wreckers” in the TsUNKhU. Those responsible for the preparation and conduct of the census were declared enemies of the people. The victims of the repressions were: the head of the Department of National Economic Accounting of the State Planning Committee of the USSR, I. A. Kraval, the head of the Population Census Bureau of the Central Committee of the USSR O. A. Kvitkin and his deputy L. S. Brand, the head of the Population Sector, M. V. Kurman, and other leaders who suddenly became “enemies of socialism – Trotskyite-Bukharinite agents of foreign intelligence services.” Needless to say, the new leadership of the TsUNKhU, which conducted the census in 1939, took into account the “mistakes” of its predecessors as much as possible. Their immediate goal was to conceal the human losses revealed by the repressed census of 1937, as well as the victims of the Great Terror who had been added to them. In part, this was done by manipulating population loss data. It is noteworthy that in March 1939, speaking at the 18th Party Congress, Comrade Stalin admitted that he himself had provoked an overestimation of the population in the mid-1930s: “Some of the old employees of the State Planning Committee believed that for example, that during the Second Five-Year Plan the annual increase of the population in the U.S.S.R. should be three or four million or even more than that. It was fantastic, too, if not worse.” As the historian and demographer A. G. Volkov notes, after such a sad experience with the politicization of statistics, the “father of nations” was no longer up to jokes about “the whole of Finland”…

Realizing the political impossibility of publishing the data of the 1937 census, the Soviet leadership simply classified its materials – scientists got access to them only in the 1990s. Today, based on these data, we can more realistically imagine what the USSR was really like by the mid-1930s.