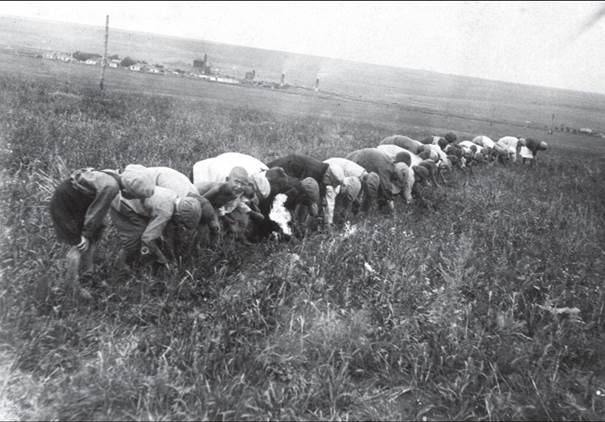

Portrait of an era. How the USSR motivated a person to work for free. On the example of child labor.

Children weeding a collective farm field.

I will immediately ask a question that arose in my mind when reading an article from a magazine in 1946 about the participation of children in collective farm work.

Why in the damned West, where children worked for money, this was called the exploitation of child labor, happily eliminated in the USSR. And the exploitation of child labor in the USSR, and completely free of charge, was called beautifully – socially useful labor for educational purposes?

At least they paid money there… And in our country, apparently, they were immediately prepared for life under communism, when commodity-money relations would die out? To be honest, I don’t understand this point.

Here’s an example I read in the article.

We have children whose parents are not clear where. The reasons for the absence are not indicated, but they write letters to each other.

The children have been living in the boarding school for several years.

At the time of the events, they were 10 years old.

Before that, they were accustomed to work skills, which boiled down to self-care: making the bed, packing toys, cleaning clothes…

But now they decided to bring to a new stage – just that amazing thing that was designated as socially useful work. We just decided that the children would be able to cope with it quite well.

At first, they were adapted to the collection of medicinal herbs. And then they were younger. This was done under the slogan of helping hospitals.

Then, when the children got their hands dirty, so to speak, on the grasses, it was decided to transfer them to a more difficult area of work – weeding collective farm fields.

Moreover, as the author says, they were previously prepared for this hard work morally – they were given political information with stories about how during the war the soldiers showed bravery and courage for the sake of the Motherland. Letters from their fathers, which they sent from the front when they were still alive, were read to them, with an emphasis on the fact that they, too, should grow up to be excellent fighters, and emphasized the fact that for this children need to learn to work. As a result, according to the author, they themselves began to ask for weeding.

To be honest, this treatment reminded me of sectarians who also pedal people’s innermost feelings in order to weave ropes out of them.

And after that, the kids were sent to cultivate the fields. In passing, it was noted that the boys were healthy and strong. To the children, this was presented as respect for their decision. (In fact, the application came from the collective farm).

Well, it’s just bravo…

Then the manipulations, and it is difficult for me to call it otherwise, continued.

The children were taken out to weed oats from wormwood and turnip.

In order for the children not to be immediately frightened by the huge fields that they had to cultivate, the author took out pegs with a rope, and measured out a small area for them. When they weeded it, I measured it further. And at the same time, she encouraged them, showing them how well they weeded the next section. Here’s the method… At the same time, the children were encouraged to work faster…

There, too, it was done wisely – they were placed in pairs, and in pairs a kind of competition was arranged. The one who worked worse was drawn to the one who worked better, and so the children cheerfully cultivated the fields.

By the way, they were also trained in the correct pulling of various weeds, so that they could distinguish high-quality work from low-quality work both in themselves and in others, as well as so that their efforts were applied more effectively.

The children, as the author notes, quickly got tired. They were given breaks – to lie on the ravka in the shade, during which the author, like Scheherazade, told them a fairy tale with a moralizing element, about hard-working heroes (of her own composition, I believe), but then interrupted it at the most interesting place, and promised to tell the continuation after they shockedly, helping the laggards, weeded the next section until the next break.

And in the end, in order to show the children how important their work is for the Motherland, a field farmer, whose three sons have been to the front, was invited to accept the results of the day’s work. And he once again pointed out to the children their mistakes in weeding (somewhere the oats had been trampled, but it was for the red cavalry – the cavalry would now not get enough oats), and only after he had made remarks – praised and promised, if they worked well, to ride horses.

In the canteen of the boarding school, a table was hung, where it was noted what each group of children did during the day: how much they weeded and what grade they received for quality and discipline. The group, which received “excellent” marks all week, was encouraged at the Sunday line-up – when the flag was raised, this group was lined up at the mast.

At the same time, the author admits that she underestimated the children’s work so that they would work even more zealously. She explains: “I have to help children understand the meaning of the words ‘Work is a matter of honor, valor and heroism’…

Also, together with the children, they wrote letters to their parents, in which they forced them to write about how they work and help the collective farm and the Motherland.

To be honest, I read it and admired it. They did! To make people work hard not for money, but for praise in the wall newspaper… And how everything is arranged! For example, in some modern enterprises, cunning owners try to pay less, pumping people with “corporate values”. But here the author presents everything as a method developed by her to introduce children to work with high goals, and very frankly reveals the whole kitchen of manipulating the consciousness of these children so that they go out of their way to work, doing it for moral praise.

I think I’m sorry, but it’s somehow more honest to pay children for their work… Since we couldn’t do without child labor anyway, let’s call a spade a spade. And it’s even more honest to call it work for free, and not hide behind lofty phrases about upbringing.

And I also don’t understand why people who believe that all this is normal today are so outraged when children are also involved in free work in monasteries. There are so many cries about the exploitation of labor… Well, sorry – they are also on the security there, if you use the same logic. It means that they are obliged to work it out as well. Judging by your own reasoning. And the materials there are also the highest possible…