The Long March. The Great Chinese Civil War, 1912-1950. Introduction. The Last Gust of the Steppe Wind: A Brief History of the Manchu Dynasty

The Great Civil War in China began with the Xinhai Revolution, which put an end to the centuries-old monarchical system in the Celestial Empire. The Qing Empire ceased to exist after the abdication (of course, not independent) of the 6-year-old Emperor Puyi on February 12, 1912. The causes, course and results of the Xinhai Revolution will be examined in detail in the first chapter of the book, which is specially devoted to it. However, the author considered it reasonable and necessary to preface this story with a brief history of the Manchu dynasty that ruled China in 1644-1912, especially since a number of prerequisites for the Xinhai Revolution are associated with the fundamental features of the structure of the state created by the Aixingyoro family, laid down at the stage of its foundation. Moreover, without historical retrospective, it will be impossible to properly understand the situation in which China found itself at the beginning of the second decade of the 20th century. Finally, some of the decisions made by the leadership of the Qing Empire before the revolution will also not be entirely clear if we do not take into account the experience accumulated by the monarchy and the administrative methods developed earlier.

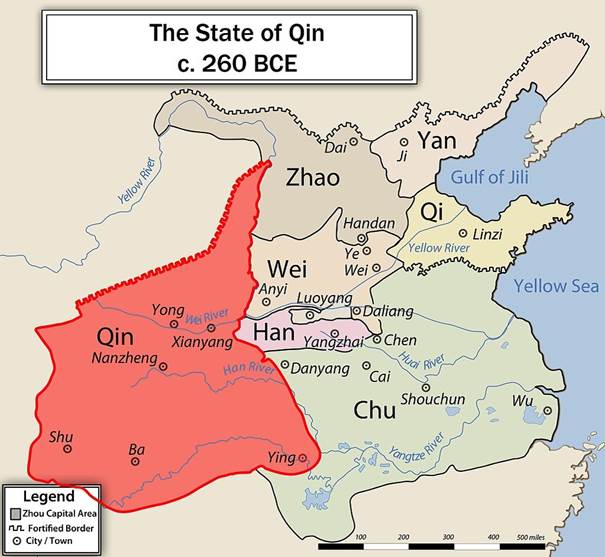

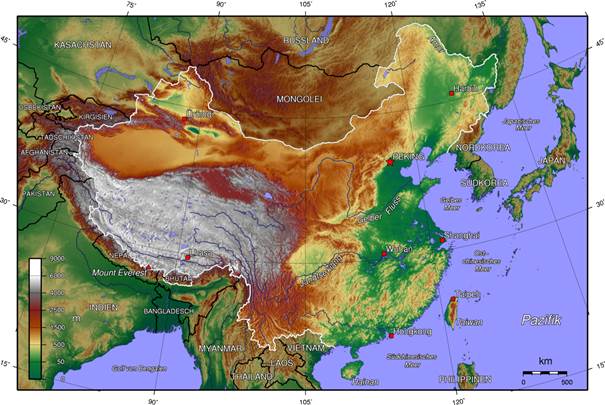

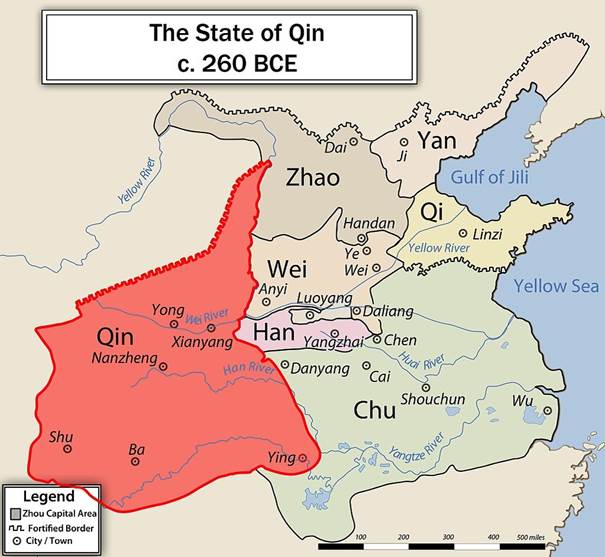

Like many other agricultural civilizations, China was formed around great rivers and the irrigation opportunities they provided. Egypt had the Nile, the Sumerians and their successors in Mesopotamia had the Tigris and Euphrates, India had the Ganges and the Indus. The core of the celestial empire is the land along the Yellow River, the Yangtze River and the space between them.

The historical heart of China: the kingdoms united by Qing Shi Huang into the first of the Chinese empires.

To the east of this region is the sea. To the south, there were the underdeveloped tribes of the Miao-Yao, about whom not much is known today, but tribal communities engaged in primitive slash-and-burn agriculture: China gradually digested them socio-economically and culturally. Although even now, which may come as a surprise to many, the largest ethnic minority in the PRC, ahead of the much more famous Uighurs and Tibetans, is the Zhuang people, the heirs of those distant ancestors who live mainly in Guangxi. Ultimately, in the south, the Celestial Empire also ran into the natural boundaries of the South China Sea and the jungles of present-day northern Vietnam. The west is the highest mountains and lifeless deserts: the Himalayan range, the Tibetan Plateau and Kunlun. But in the north, historical China has always bordered on the vast open space of the Great Steppe. And without any natural obstacles that can serve as a line of defense.

Physical and geographical map of modern China

The first emperor to unite the Celestial Empire into a single state, Qin Shi Huang, began to build the Great Wall, a symbol of China, a structure as majestic and large-scale as it was useless. Because practice has shown that the Celestial Empire is not able to fence itself off from the Steppe and the nomadic peoples living in it, no matter how far the builders extend the artificial barrier.

There were many reasons for this. On the one hand, there are purely military ones. Although it already had a large population and was capable of fielding a large army, China could not saturate its monstrous fortifications with troops with a sufficient degree of density to be able to really repel a massive invasion. It was too costly to keep hundreds of thousands of warriors as a kind of “Night Watch” in peacetime, constantly guarding the Wall. More modest garrisons were able to play the role of observers and signallers at best. Every now and then there were gaps in the defense, which the enemy invariably successfully exploited, since he was mobile and easy to climb: there were always those who wanted to profit at the expense of the settled in the Steppe. On the other hand, even though the Celestial Empire quite early formulated self-sufficiency as an ideal for itself and sincerely believed that it was the Middle Land occupying the best position, around which there was a deliberately less developed and harmonious periphery of the world, trade and economic interests prompted the Chinese to establish more and more extensive contacts with other countries. The Great Silk Road certainly already existed in the first centuries of our era, and by the 3rd or 4th centuries after the birth of Christ it had become, perhaps, the largest and most important highway of its kind in the world. And a significant part of it, whether it was the northern or southern route, passed through the lands of the steppe people. Accordingly, there was a need for interaction. The Chinese could fight with the nomads, or look for common ground for cooperation, but to fence themselves off and forget about their existence – no, it became absolutely impossible.

The Great Silk Road around the 1st century AD.

Within the framework of this work, there is neither space nor sense to retell, at least briefly, the history of interaction between the Celestial Empire and the Steppe. Rich and diverse, it dates back many centuries. Let us highlight one point that is important in the context of the further narration. China faced the need to carry out active operations against nomads on their territory quite early. In order to prevent a prosperous aggressive ethnos from strengthening and rallying the rest around itself. As a preventive measure to precede another robbery raid. To demonstrate strength that could serve as an argument in the further diplomatic process. There are many options. The essence is the same. For the predominantly poorly trained infantry, this task proved to be extremely difficult. Large contingents of troops sent to the Steppe faced terrible logistical difficulties. If the size of the armies decreased, it often turned out that, without a large numerical superiority, it was difficult for the soldiers of the Celestial Empire to resist exceptionally mobile and highly experienced cavalry. In addition, the campaigns, contrary to all the canons of Chinese military science, turned out to be protracted and “viscous”. Those strategic points for which the struggle could be imposed on the enemy, the steppe people de facto did not exist. Every now and then the Chinese found themselves in the position of a man striking the water with his fist. It seems that the blow passes, the splashes fly in all directions. And then the flowing liquid closes again, as if nothing had happened. Often, it was several times cheaper to give a gift of silk or other tribute from some khan than to chase after him for several years with a minimum result. And, even if this particular leader is defeated and killed, very soon a new horde will arrive in his place from the Tumbleweed Steppe.

The solution was the emergence of China’s “own” nomads. Actually, in fact, the situation here is somewhat more complicated. It cannot be said that at one time or another some rulers of the Celestial Empire consciously chose the tactics of adapting and incorporating certain steppe tribes into their military machine. Quite the opposite. The consolidating nomadic world gave rise to a sufficiently powerful conqueror who took possession of the Celestial Empire (or its northern part), and the sinicizing descendants of the latter nevertheless retained a connection with the former ancestral homeland and some techniques gleaned from it. The Northern Wei Empire, which existed from 386-535 AD, was founded and led by the Toba clan from the Mongol-speaking Xianbi ethnic group. Northern Zhou in 557-581 was ruled by former nomadic Tabgachi. Finally, even in the Tang Empire, which is considered by many in China to be the pinnacle of national development (if we do not take into account modern history) and a model of power, Li Yuan, a feudal lord from the border province of Shanxi, who created it, brought some elements borrowed from his steppe neighbors.

Li Yuan is the founder of the Tang Dynasty. By origin, the Tabgach is a descendant of the Sinicized steppe Toba, described by Gumilev as an ethnos “equally close to China and the Great Steppe.”

Their nomads were not inferior to the hostile ones in terms of mobility, could carry out fleeting punitive operations, close in essence to raids, and did not experience the numerous difficulties that a regular imperial army had to face. It is another matter that, while preserving their internal autonomy and selfhood, being an ethnos and not a subdivision, they could in some cases take an independent political position. First of all, when they felt that their interests were being infringed, or when the central government was weakened and crisis. Some parallels can be drawn with the federates of late Rome.

Anyone who has read the maps depicting the historical states of China has noticed how much they sometimes differ from one source to the same empire. This is due to special forms of vassalage, which are noticeably closer to tributary than to classical feudal practices. On the one hand, the predominance of the Celestial Empire in certain periods was theoretically recognized by almost all of its neighbors. Let’s say, the Wangs of Korea. And, for example, the history of the Imjin War of 1592-1598 clearly shows that China regarded the aggression of any external forces against such vassals as an attack on its own interests. The process of economic interaction was widely developed, and culture and practices were intensively adopted and adapted. In many respects, the bodies surrounding the main luminary measured themselves according to Chinese patterns.

On the other hand, Korea has never been part of the Celestial Empire in the sense that its administrative system remained independent and was not integrated into the all-Chinese system as an integral element, even if it was autonomous. Both the bureaucratic vertical and the feudal ladder were absent. Even with the highest degree of loyalty of the Korean state to its “big brother,” the two spaces remained clearly demarcated. And, for example, the situation quite typical of Europe, when the same family would own land in China and Korea, with double and triple vassal-seigneurial ties, was completely excluded. As well as the appearance of a certain Chinese “proconsul” near the wang, whose power and power capabilities would be based on the military grouping of the metropolis stationed in the region. The interaction was carried out strictly indirectly. The Korean cities could not have their own obligations or, on the contrary, the privileges granted by the Chinese emperor, they could not appeal to his authority, as the communes in Europe of the same time, offended by their dukes and counts, did.

Vassal ties with the imperial center of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples were all the more limited and conditional. Their internal structure and methods of management automatically separated them from the agricultural environment. The dynamism of the steppe dynamism allowed them to avoid the undesirable aspects of their interaction with the Celestial Empire in the simplest and most reliable way: by migration. And yes, going back, the local rulers and khans could say that they did not even think of breaking with China, but simply solved their own local problems, not daring to bother the great heavenly lord because of them. Even raids on border villages were sometimes passed off as “local misunderstandings” too minor to call into question loyalty to the emperor. And, of course, this was a game of mutual hypocrisy. The central officials, as a rule, understood the value of the loyalty of the nomads, but they were also good at counting – and, realizing how much more expensive a good quarrel would be compared to a bad peace, they pretended to believe simple-minded deceivers.

All of the above allows us to finally get to the point. Who was the Aishingyoro clan and what position did it occupy? The founder of the surname was Nurhaci from the Jurchen clan of Tong.

Nurhaci Aisingyoro. The image is not alive, so his appearance may have been different.

His ancestors lived in the area of Mount Paektu, that is, in the realities of the mid-16th century outside the Ming Empire. At the same time, the Jurchens as an ethnic group have been in the orbit of the Celestial Empire for a very long time and were connected to it by thousands of threads. By the time of Nurhatsi’s birth, the history of interaction, in which one or another Jurchen sub-ethnic group often had to act as “their nomads,” went back more than six centuries. In 1115-1234, it was in the Jurchen iteration that there was another North Chinese power with a strong steppe element – the Jin Empire, which was eventually crushed by Genghis Khan. By the early 1550s, the Jurchens could be divided into three groups. Some of them, who lived on the Liaodong Peninsula and to the north of it, were direct subjects of the Ming dynasty, since these lands were part of the Imjin province and were ruled by hereditary Chinese landlords. In practice, however, the control of the settled administrative apparatus over the life of nomadic families and clans could be quite conditional. On the other hand, kinship and economic ties with the “Chinese Manchus” additionally tied to the Celestial Empire those Manchus who lived further to the northeast – the latter can be called vassals. They, at least the majority, accepted the primacy of the Empire in theory, as long as this formal dependence did not create practical burdens for them. Finally, still farther north and east were the “free” Manchus, who did not consider themselves bound by any obligations to the Ming dynasty, even in theory. This, however, did not mean automatic hostility. All three categories seemed to flow into one another quite freely. And each of them, even the “free” Jurchens, experienced a powerful cultural influence from the great southern neighbor. In particular, it was expressed in their gradual settling on the ground.

Map of the settlement of the Jurchen tribes by the end of the XVI century.

The Tun clan, as already mentioned, originally lived in the area of Mount Paektu, but due to some conflict with the Korean Joseon Dynasty, they were forced to leave their homes. It was much harder for them than for their conventional ancestors of the 13th-14th centuries, because, although they were actively engaged in cattle breeding, the Jurchen-Tong lived in stationary villages and even built several small fortresses. Having shifted from the former area, the ancestors of Nurhatsi obviously affected the zone of interests of other Jurchen clans. In particular, the ruler of the Jurchen town of Turun, Nikana-vailan, turned out to be offended. The latter had connections with the Chinese bo (for simplicity’s sake, it can be compared with the count) of Liaodong. The Tong never swore allegiance to the Ming Dynasty. But, I repeat, this does not at all follow from their initial irreconcilable hostility. What’s more, they’d probably go for it if they had time. But first, by presenting the settlers as an uncontrollable aggressive force, Nikana-vailan managed to bring down Chinese thunders on their heads. Bo Li Chengliang, who in principle and not without reason was wary of the incomprehensible encroachments of the steppe people (by that time he had managed to repel four invasions of the Chahar Mongols), organized a punitive campaign in 1582, during which Giochangi and Takshi, Nurhatsi’s grandfather and father, were killed. Nevertheless, the Tong clan did not disappear, and the young baile, who was born in 1559, managed to retain power.

His further actions could be considered a deliberate multi-step revenge, but in reality, Nurhaci was more likely just trying to survive. His first step was to repay Nikan-vailan. According to legend, in 1583 Nurhatsi with a group of only 13 mounted warriors made a raid on Tulun, took the city, but his enemy himself was able to escape. Even if the number of people who fought under the command of Nurhaci is deliberately underestimated for greater intensity of heroic pathos, it still says a lot about the scale of events in general and the size of the Jurchen settlements in particular. This was followed by a process of consolidating Nurhaci’s power over a small region in the valley of the Suksuhe Bira River (present-day Suzihe), which took several years. It was this region with six cities (of the caliber of the above-mentioned Tulun) that received the name Manchuku, which in turn became the basis of the Manchu ethnonym.

It should be understood that there was no question of any irreconcilable antagonism between Nurhatsi and his tribal confederation grouped around him, on the one hand, and the Minsk authorities of the northern border area. Thus, in June 1586, Nurhaci stormed the city of Erhun, where Nikan Vailan was hiding. The latter managed to escape to Liaodong, China, but Minsk border officials, probably for a bribe, or perhaps just as a gesture of goodwill, handed him over to Nurhaci, who immediately executed his enemy.

The consolidation process, meanwhile, continued as usual. By 1589, Nurhaci had united all the Jurchen tribes that had settled northeast of Liaodong. In 1591, the ruler of the Manchus organized a military campaign against the Yalu tribe and completely conquered it in the same year. By 1599, Nurhaci had completed the conquest of the Changboshan Unification – Yalujiang, Neyin, and Zhusheli. Perhaps it was only at this point that his actions went beyond the regular fluctuations that had occurred in the region before. In principle, Nurhaci continued to gradually subjugate the disparate Jurchen tribes until his death in 1626. It is only in the last decade that the Chinese have begun to act as its opponents on a systematic basis, supporting any opponents of the Manchus.

Nurhaci was a successful and untalented military leader, but he did not accomplish anything truly extraordinary in this field. Far more important for the further triumph of his descendants were the internal reforms he carried out. But for the most part, they escaped the attention of Minsk observers, who arrogantly considered Nurhatsi to be nothing more than an adventurer. What were these innovations?

First, instead of the already very amorphous Jurchen identity, Nurhaci formed a much more coherent and cohesive Manchu identity. He relied on the tribal nobility, allowing it, breaking away from its traditional position in the clan community, to turn into a full-fledged military aristocracy that owned considerable wealth, in particular, slaves, who were obliged to work for the master and were deprived of the opportunity to migrate. Equally important, Nuhatsi institutionalized his power in a fundamentally new way. Initially, while reducing his dependence on his own Thun clan, he, like many others, sought a source of legitimacy within the Empire. Nurhaci traveled to Beijing, where he obtained an audience with Emperor Wanli, accepted the title of “commander of the tiger and dragon” with a salary of 800 liang and permission to wear ceremonial clothes of the Chinese model. But then he found something else entirely. Nurhaci began to appeal to the heritage previously mentioned in the text of the Introduction of the Sino-Jurchen Jin Empire.

The Jin Empire at the Height of Its Power

The Tong clan is said to have descended from one of the branches of her ruling dynasty. Having made this genealogical discovery, Nurhaci renamed his own surname Aisin Gyoro, that is, the Golden Family, since Jin means “Golden” in Chinese. Thus, his dynasty turned out to be much older than the Ming dynasty and in its power prerogatives was initially independent of it. In 1589, Nurhaci declared himself a van, in other words, although he did not claim the imperial dignity (huangdi), but an independent ruler. In 1606, the Eastern Mongol princes also gave him the title of Khan, but it was not the name that mattered much more important, but a separate, independent source of honor and power. In 1616, Nurhaci proclaimed himself monarch of the reorganized Jin state. And this, albeit indirect, is already a claim to the Mandate of Heaven and vast territories that were once Jin, and are now part of the Ming Empire.

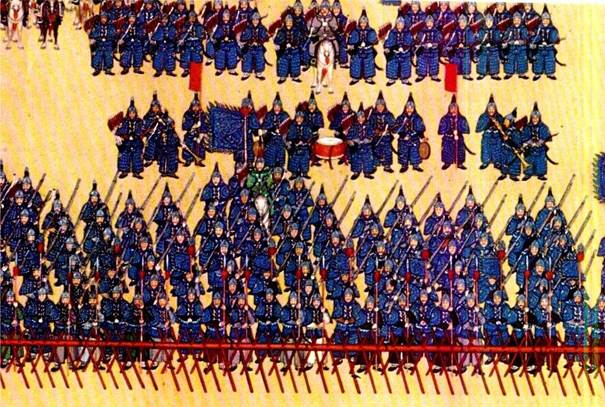

Second, and no less important, Nurhaci carried out a large-scale reorganization and streamlining of his armed forces. The system he built was simple, austere, and in many ways reminiscent of the one created by Genghis Khan. Military units served at the same time as a form of administrative hierarchy for society as a whole. According to the order established by Nurhaci, a combat unit of 300 warriors was called a niru, five niru made up a chale (1,500 people), five chales made up a gus (7,500 people), and two gus made up qi, a “banner” (15,000 people), close in essence to a tumen. It is important to understand that, for example, a niru is not only 300 warriors directly on a campaign, but also a certain number of families capable of fielding them. Banners, in addition to the conventional one, also had a completely literal meaning – the soldiers who were part of them really wore banners of one of the following colors: yellow, red, blue or white.

Yellow Banner of the Eight-Banner Army

Initially, at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, as it is easy to understand, there were four of them. Later, as Nurhaci’s power strengthened and the space under his control expanded, four new corps were created in 1615, which received banners of the same colors as the previous ones, but with a border on the edges: the red banner had a white border, the others had a red border. In this composition, the Manchu armed forces became known as the Eight-Banner Army. It was predominantly a cavalry, disciplined, experienced, and, most importantly, highly combat-ready force.

In 1592, Nurhaci’s son Abahai was born.

Aishingyoro Abahai

It was he who took power after the death of his father, who did not specify who exactly would succeed him. The method is remarkable. Abahai was elected Great Khan at a gathering. This, of course, speaks volumes. The dynasty had not yet been established, and in the course of expansion, many ethnic groups were included in the Later Jin, for whom the steppe kurultai traditions were much closer than the approaches of the Sinicized Jurchens. However, it was one of the last outbursts of this variety. Both the policy of Abahai himself and the measures taken by his father contributed to the establishment of new principles of interaction between the authorities and society.

The war with Ming China had been going on without interruption since 1618, but what kind of war was it? When Nurhaci announced the revival of Jin, of course, Beijing was not eager to recognize his new status, but then many factors overlapped with each other, due to which a powerful campaign against him was never organized. In the first place, the Manchu ruler, even now, was not yet taken seriously as a really dangerous menace. Secondly, Beijing did not want to raise the status of Nuhaqi by any large-scale emergency actions, elevate him to the level of a rival of the Ming dynasty and thereby symbolically recognize him as an equal. Thirdly, the Empire had already begun to experience quite significant internal difficulties, and the campaign against the Jin promised many costs and problems, but a minimum of benefits. Finally, although his swing seemed obvious, Nurhaci did not take any really aggressive steps, and therefore the fight against him did not seem to be the most urgent thing. Apparently, the Chinese preferred to “shake” the young neighboring state from within, since it seemed to them rather loose and amorphous. And provoked a response. In 1618, Nurhaci published a manifesto entitled “Seven Great Grievances,” in which he outlined what he considered to be the main crimes of the Chinese against his people and himself. In the same year, Nurhaci’s 20,000-strong army invaded Chinese territory in Liaodong, capturing three important fortresses and five cities.

A Manchu warrior of the period described

All the claims on Nurhaci’s list were purely local and personal: accusations of the unprovoked murder of his father and grandfather, support for the Yehe clan hostile to the Manchus, and the like. They contained neither a direct nor even a veiled threat to the existence of the Ming Empire as such, and did not question the rights of the ruling dynasty. And, accordingly, they left room for diplomatic manoeuvre followed by reconciliation. This is how the Chinese authorities perceived everything. The leader of “his” steppe dwellers, who have warmed up in the light of the Celestial Empire, is rowdy, trying to get better conditions for vassalage for himself – on the verge of complete freedom and with the recognition of all his conquests. But there is no threat to China here.

In 1619, the Empire allegedly sent an army of 200,000 men against the Jin/Manchuku, which attempted to march on the capital in four scattered corps, but was defeated by Nurhaci piecemeal. However, there is a nuance. We know all this from later Qing testimonies. That is, the Aishingyoro dynasty, which already ruled China, painted its own heroic past. No, the hike, apparently, really happened. But with more modest forces. The Chinese underestimated their enemy, broke away from their supply bases, and their corps were isolated from each other and defeated – a typical plot in the history of the Celestial Empire. Nevertheless, it was not this defeat, but later events that made the Ming Empire seriously worried. In 1621 the Manchus invaded the Liaodong Peninsula. Their actions are a combination of classic nomadic tactics, such as mass deportation of prisoners, with principles characteristic of the combat work of the regular army. They do not hesitate to adapt the enemy’s equipment and tactics, and use captured guns. Units of the Eight-Banner Army manage to take the city of Shenyang, which Nurhaci renames Mukden in the Manchu manner. In 1625, the capital of his state was moved there. At the same time, in 1622, the army of the Later Jin for the first time launched an offensive in the southwestern direction – to Liaoxi.

It was in these conditions that the Minsk government began to move. It began to renovate the old defensive lines – figuratively speaking, the eastern end of the Great Wall, to gather additional military contingents. At the same time, the Korean vassal ally was asked to distract a common enemy and buy time. The Joseon Dynasty itself was not interested in the emergence of a powerful new power on its northern borders, so it agreed quite easily. It was the Koreans that Abahai had to deal with in the first place after his accession to the throne. No, first in the beginning of 1627 he organized a raid on China, first, as a demonstration, especially to domestic observers, of his power and ambitions, and second, of course, for the sake of booty. This is the style of the steppe nomad, which would have acted in exactly the same way three centuries ago, and in the previous millennium in general. But Abahai struck a full-fledged blow – and here the duality of the Manchu state was manifested – on Joseon in the same year. After crossing the Amnokkan Ice, a 30,000-strong Manchu army under the command of Wang Beile’s cousin Amin invaded Korea. By April 18, it forced the Koreans to admit defeat and pledge to pay tribute to the Manchus.

Korean warriors during the Imdijn War of 1592-1598. Over the past 30 years, their appearance and armament have changed little. In general, the consequences of the Imjin War, in which Joseon suffered huge material losses and human losses (up to 1 million soldiers and civilians combined), were still being felt by Koreans by the mid-1620s.

Units of the Eight-Banner Army ravaged cities, turning the inhabitants into slaves, but when a serious enemy approached, they reorganized, united, and fought successful field battles.

And then the fun begins. Abahai strengthened his position on the throne, eliminated the flank threat, and generally stabilized the position of the country. It would seem that the right time to go on a decisive campaign against the Ming Empire – or put up with it if you lack courage. Instead, Abahai lets the conflict hang in the air. And it was a truly brilliant strategy. On the one hand, the Manchus created tension and ravaged the border area like classic nomads, forcing the enemy to maintain constant readiness and mobilize large contingents of troops. In 1629, after bypassing the fortresses of Liaoxi and breaking through the Wall to the west, Abahai’s forces raided almost all the way to Beijing – and then retreated, taking advantage of the advantage of speed and initiative when they were pinned down. On the other hand, Wang was doing something much more important: he was turning his state into a second, alternative China, allowing it to mature in the archaic society of the steppes as if in a shell, while he was busy with his favorite business, squeezed by the pincers of military necessity. In 1629, in the Later Jin/Manchuku, the Chinese examination system was introduced for future officials and military commanders, and the Secretariat was organized, which conducted state records management. In 1631, a government was established, a system of “six departments” similar to that of the Ming Empire at that time. Defecting Chinese officials were appointed to a number of posts.

Abahai did not let the enemy go, did not allow him to strike back. At the same time, the fruitless mobilization efforts themselves only further undermined Minsk China, which was already rapidly losing internal stability. In 1628, due to exorbitant taxes and general inefficiency of administration, a peasant revolt broke out in Shaanxi Province. It will gradually expand and last for 19 years. The rebel leaders, although unable to reach an internal consensus, drew hundreds of thousands of people into their movement. The strategic rear of the Ming Empire received a heavy blow. And most importantly, many influential people at the provincial level began to feel that the very social fabric they were accustomed to was about to be torn apart, threatening a grandiose redistribution of property. At the same time, the court lives in a kind of world of its own and fights in the north in a very strange way: there are no battles, but the soldiers stand still and, of course, consume a lot of food, and receive their salaries for free. without uprooting the roots. Victories made the center believe that the problem could be solved by purely forceful methods, and the ruined peasants – both those where the authorities were still working and regularly collecting taxes, and those where the state was supplanted by the arbitrariness of local rulers, who were in a hurry to accumulate a sufficient “safety cushion” for a rainy day, rebelled again.

In the meantime, Abahai works very competently and consistently for self-strengthening. Until the early 1630s, he subjugated all the Jurchen chieftains who still retained their independence. He then enters Mongolia, not as a conqueror, but as a partner and protector: he calls on the local princes to strike with him at the much more Sinicized (and wealthy) Chahar, and then further south, which the Mongols alone would not have had the strength to do. Implicitly, within the framework of the same process, its political predominance and then domination are asserted. In 1632, a ruinous campaign to Chahar enriched the northerners and undermined the authority of the Ming ally Ligden Khan. Many rulers preemptively go over to the side of the Manchus. In 1634, when Ligde Khan died of smallpox very successfully for Abahai, the process took on a landslide. By the middle of the decade, the whole of Southern Mongolia was already in favor of the new ruler. Abahai is asked to accept the title of Great Khan (Bogd Khan). And at the same time, after the defeat of Chahar, the relatives of Ligden Khan gave him a certain seal (the exact origin of which has not been established), which was said to be the imperial seal of the Yuan Empire. The Manchu sovereign willingly uses any means to assert his prerogative. De facto, it moves along four paths at the same time. In the first place, Abahai rules over the Manchus in the narrow sense as the son of his father and the chosen one of the kurultai of 1626. Secondly, he is descended from the Golden Family and inherits the ancient Jin Empire. Thirdly, Abahai became the god khan of the southern Mongols. And finally, through them, now also the Yuan seal. Taken together, he decides that he has progressed far enough to justify the last step. On May 5, 1636, he assumed the title of Huangdi Emperor with the very significant and precise motto of his reign “Chunde” (“Accumulated Grace”), and also renamed his state the state of Qing (from the Chinese “pure”) in a new full-fledged status.

Map of Asia for 1636 – the moment of the proclamation of the Qing Empire.

In 1637, at the head of an army of 100,000 men, Abahai made a campaign to Korea. In some sources, one can read that it ended with the conclusion of a treaty according to which the Korean Wang renounced the alliance with the Chinese Empire. The reality was a little different. By and large, Korea retained its alliance and vassalage towards China, only the latter was now replaced by the Qing Empire. This was evident from a number of characteristic symbolic gestures. Thus, Joseon had to abandon the old chronology, similar to the Minsk one, and switch to the Qing one. All diplomatic and trade relations with the Ming Empire ceased, as if it ceased to exist for Korea. On the other hand, once again combining the practices characteristic of Chinese statehood with the traditions and approaches of the steppe people, Abahai did not forget to guarantee himself a quite significant material gain, once again increasing the amount of tribute due to the Manchus. In general, the victory was achieved very quickly. Units of the Eight-Banner Army crossed the border in the very last days of December 1636, and on February 11, 1637, it was all over.

Convinced of his strength, Abahai revised his plans for the Ming Empire. Previously, his strategic plan was a large-scale envelopment from the west: concentrating in southern Mongolia, the Manchu troops were to invade Jilin and further develop the offensive to the south. Such a plan was the safest and promised an easy but incomplete victory. In the event that the main forces of the Ming Dynasty remain in the area of Beijing and the fortresses covering it, the Qing troops will be able to plunder, swagger, and certainly defeat some of the enemy’s field troops, but on the whole it will still be more of a grandiose raid than something more. The system of governance of the opposing state can still be preserved. Finally, finding themselves in a critical situation, the Mins can take a desperate step and go all-in, launching their own offensive on Mukden. And for Abahai, who, behind the screen of nomadic bogdakhanism, was creating a completely modern administrative structure by the standards of the era and the region, this threatened to become a very unpleasant surprise. The Manchus created their own artillery park and gained experience in storming fortifications. In short, Abahai decided to attack directly.

The “gnawing” through Liaoxi lasted about three years. For the first time, successes were given to the Qing troops with such difficulty and at such a high price. Nevertheless, the fortresses defending Liaoxi were taken: Bijiagan, Tashan, Xinshan, Xiaolinhe, Songshan and Jinzhou. The only thing left to do was to capture the largest of all, Shanhaiguan. And then, unexpectedly, Abahai Aishingyoro, aka Emperor of Hongtaiji, died suddenly on September 21, 1643, at the age of 50. This unexpected blow almost became the pebble on which the Manchurian expansion stumbled. The heir was still very young: Aixingyoro Fulin had recently reached the age of six.

Aishingyoro Fulin. In the picture, he has already reached the age of majority.

And yet, the Qing Empire managed to maintain its momentum. Why? First of all, the dynasty was established. No matter how small Fulin was, no one dared to question his rights. All traditional nomadic procedures, at least formal ones, are also a thing of the past: the new emperor did not need to be approved by a kurultai or anything like that. The Aishingyoro family could be proud of themselves. Secondly, Fulin was very lucky with his uncles. When, after the death of Abahai, a council of princes of the ruling house was convened, attempts to play with the succession to the throne even within the family were decisively suppressed by Dorogon, the younger brother of the late monarch, who, in fact, was expected to be the new ruler instead of the child. In general, it is necessary to say a few words about this person. Aishingyoro Dorgon was one of the best military commanders in the Manchu army. During Nurhaci’s lifetime, he held fifteen nira in the army of the Yellow Banner. Then, in the era of Abahai, he distinguished himself in the campaign against Chahar and soon after led the White Banner. With the creation of the system of “six departments” in 1631, Dorgon received the post of head of the department of ranks (libu), responsible for the entire personnel policy, that is, he became the second person after his brother in the Manchu state. At the same time, he did not stop his participation in the military enterprises of the young empire. For example, he led a campaign/raid on the northern Ming borderland in 1638.

And now this powerful and experienced man preferred the bird in his own hands and the stability of the dynasty to the crane of personal autocracy. For the time being, Dorgon also found a strong ally in Prince Aisingyoro Jirgalan, the sixth son of Nurhaci’s younger brother and a high-ranking commander of the Eight-Banner Army. He also supported Fulin’s priority. In turn, Dorgon demonstratively shared the regency with Jirgalan, so that no one would have a reason to reproach him for hidden usurpation under the mask of noble modesty. Later, for a number of reasons, the junior co-regent would still be pushed out of power, but during the crucial period, the configuration that developed around the throne of the Qing Empire was just that.

Aysingyoro Dorgon

The skillful and confident leadership of Dorgon allowed the previously outlined plans of the Manchus to develop almost without interruption. The proximity of the large-scale invasion of the Eight-Banner Army, which was to follow immediately after the assault on Shanhaiguan, was obvious to everyone in the Ming Empire. And in the end, this conviction had such a strong influence on the political situation that it did almost all the work for the Manchus! The authorities strengthened Wu Sangui’s border army (which was still inactive). The south of the country was left almost without troops. The North was expecting an imminent disaster. In both cases, and against the backdrop of rebellious peasants, the local elites preferred to act on the principle of “every man for himself” and, without directly refusing to obey, sabotage the orders of the center. The latter was especially easy given the monstrous corruption of the Minsk bureaucracy. The supply of the army (all except Wu Sangui’s unit) from just bad became intolerable. Yesterday’s villagers did not want to fight against insurgents like themselves, in whose place they could easily have found themselves, if fate had turned out a little differently. Under these conditions, the greatest of the rebel leaders, Li Zicheng, decided to launch a rapid offensive against Beijing – and unexpectedly succeeded. The resistance of the Minsk troops opposing him simply collapsed. And Wu Sangui did not go to help the capital. On the one hand, they feared a Manchurian blow to the rear. But, in addition to purely military ones, there were obviously political reasons. In April 1644, Beijing surrendered to the rebels. The last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, took his own life by hanging himself from a tree in the imperial garden at the foot of Jingshan Mountain.

And now the moment of fork has come, the point of bifurcation. There were three possibilities. First, Wu Sangui could recognize Li Zicheng as the new emperor and hold out to Shanhaiguan as long as he tried to consolidate the country. This gave China a chance to renew itself and hold out against the Manchus, but Wu Sangui personally promised little benefit. Second, Wu Sangui will refuse to recognize Li Zicheng and try to drive him out of Beijing by pledging allegiance to one of the side branches of the old imperial house. This potentially gave Wu Sangui a chance to become the first person at the new Minsk court, but it was fraught with great risks – both for the country and for him personally. He might not be able to take Beijing right away, the loyalty of his soldiers could be called into question, and the annihilating offensive of the Qing troops could begin before Wu Sangui and Li Zicheng finished sorting things out. And finally, there was a third option. Less obvious, but eventually embodied in reality. Wu Sangui and his army went over to the side of the Manchus and voluntarily surrendered the Shanghaiguan fortress to them.

This act was one of the turning points and the most controversial moments in the history of the Celestial Empire. Can Wu Sangui be considered a traitor, and if so, to whom or what did he betray? The general did not swear allegiance to Li Zicheng, did not break his oath of allegiance to the Ming dynasty as long as the legitimate monarch was alive, and did not betray anyone’s trust. But, at the same time, he opened the way to domination over the Celestial Empire for a powerful and ruthless conqueror. And this is where the most subtle point arises. Who is the Aishingyoro clan and their state? Pretenders to the throne of China, or a force external to it? Both the first and the second statements can be supported by many facts.

On the one hand, even before the conquest of Beijing, the Qing Empire reproduced many of the characteristics and forms of Chinese statehood – and they were listed above. Exams for officials, the “six departments”, mottos and symbols – everything comes from the Celestial Empire. How can we talk about the subjugation of the country by hostile foreigners if the old foundations of social relations and even most of the iconic elements of the superstructure are preserved? The Qing Empire and the Ming Empire are phenomena of the same order, elements of a continuous internal Chinese political process, where the dilapidated power vertical is replaced by a younger and healthier one, but on the whole similar to the previous one in its systemic foundations.

On the other hand, the Manchus, after all, are not Chinese. In the middle of the 17th century, they had their own language, names, and customs. The enemies who had captured the Celestial Empire earlier also became sinicized over time, dissolved in it. The Yuan Empire grew from the largest ulus of the Mongol empire, so that in the end the descendants of Kublai Khan became the most perfect Chinese in their habits and manner of rule. But this did not in any way take away the weight of Mongol domination, especially at first. The Manchus, as it were, pre-empted the passage of time here, began the process of convergence and languishing in the Chinese melting pot even before they had taken possession of the main prize. However, this could not prevent them from creating a system in which the people would turn into an estate, a privileged social stratum. In fact, this is what happened in the end.

So is Wu Sangui a traitor or not? It is impossible to answer this question unequivocally, because the events took place at the end of epochs, where for an earlier era the answer will be one thing, and for a later one another. In the context of a feudal formation, the general of a dying empire did nothing particularly wrong. But the world was already entering other times. In Europe, nations were formed, capitalist relations and the bourgeoisie were strengthened. With Wu Sangui’s legacy harmless to traditional society, China will eventually enter the Industrial Age. And then, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the fact that the Manchus are not Chinese after all will still affect the Celestial Empire, and very dramatically.

However, let’s get back to the narrative of events. Wu Sangui personally arrived at Dorgon’s headquarters, where he agreed on an alliance on the terms of free passage for the Manchus. Shanhaiguan was surrendered. For Li Zicheng, who was in Beijing, what was happening was no secret, but he had too little time. Everything. To reorganize and retrain their motley army, To purge the Minsk loyalists and petty independents in the south. To agitate and disintegrate Wu Sangui’s army. The storm was approaching too fast – and the self-proclaimed emperor had only to move to meet it…

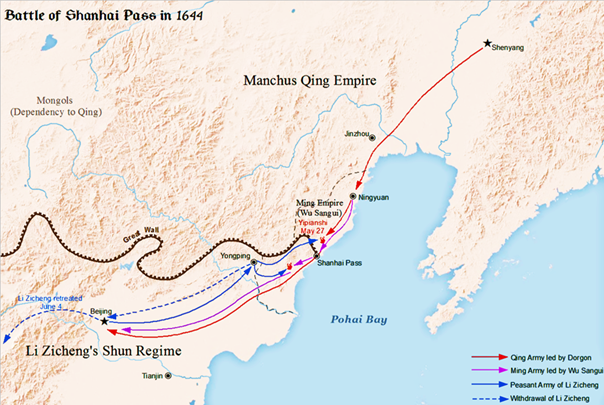

The Movement of the Three Armies, the Battle of Shanghaiguan and Its Aftermath

The general battle took place on May 27, 1644 at the Great Wall. According to some sources, there were 400,000 fighters with Li Zicheng. The problem was that they had no strengths other than numbers. Dorgon ordered Wu Sangui to throw all his forces into battle to exhaust the peasant army. The Chinese fought the Chinese, and then, at the decisive hour, the Manchu cavalry struck a devastating blow from behind the soldiers of the defecting general, from his right flank.

Li Zicheng lost. Realizing that if he was trapped in Beijing, his already weak and unstable administrative vertical would simply dissolve into space, the former rebel leader left the capital on June 4, 1644. But Li Zicheng miscalculated. Combined with the defeat, the flight undermined his authority. Those who were still willing and able to resist the Eight-Banner Army were grouped around the heirs and pretenders of the House of Ming. At the same time, on the other side of the front, at the very last moment, Dorgon did not allow Wu Sangui even to approach Beijing, but ordered to bypass the capital and hurriedly pursue Li Zicheng’s army. The Regent himself, with a part of the “banner” troops, quietly entered the Forbidden City on June 6. Gradually, with the arrival of new “banner” troops, the Manchus openly established power over the entire capital. All residents of Beijing were ordered to shave their heads and leave a scythe on the top of their heads, which meant allegiance to the Qing state. This symbol of obedience will endure in China for years to come. Dorgon announced that the capital of the empire – the already existing, Manchu empire – was being moved to Beijing. A few months later, Fulin was brought there to be re-proclaimed emperor on October 30, 1644.

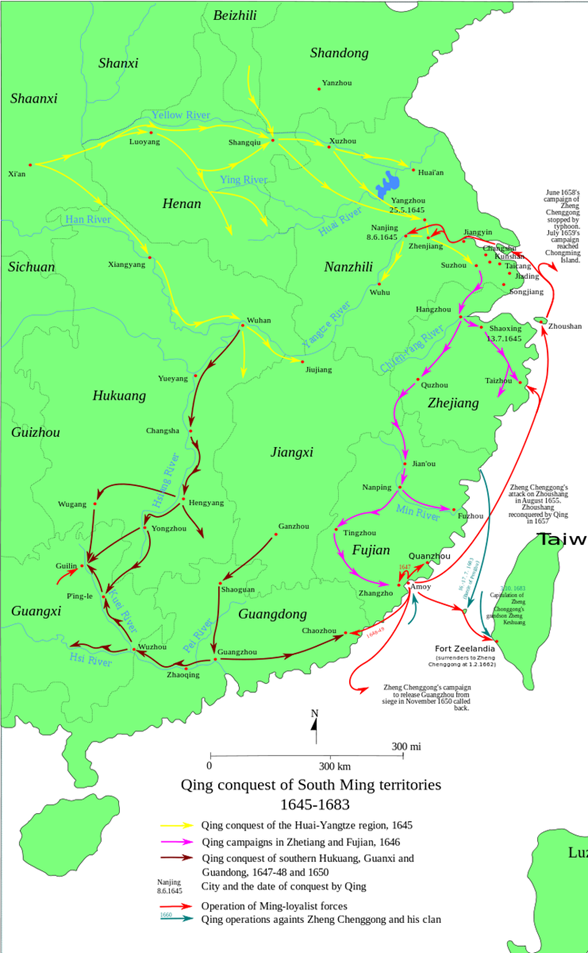

The war dragged on for a long time, but its outcome was predetermined. Most of China had become part of the Qing Empire by the early 1650s. The Southern Ming, the strongest and most dangerous of the Aishingyoro opponents, was finally destroyed by 1662. Well, the process was completely completed in the early 1680s.

Manchu conquest of China

For us, in the context of the general tasks of this work, it is necessary to highlight the lessons that the Golden Clan learned from its successes, the political foundations of the Manchu system, which remained with it until its very end.

The first postulate is to be Chinese and non-Chinese at the same time. We have already covered some of this aspect above, but it makes sense to make some additions. The Jurchens began to undergo sinicization, but if in their case it was largely spontaneous, then the Manchu elites resorted to it as a conscious and multifaceted practice deliberately. As a consequence, even before the Ming Empire proper, they managed to create an alternative quasi-China in the north to some extent. After 1644, the process reaches its logical end. There is nothing in the self-designation of the Qing Empire that would indicate its Manchuness. In addition, along with it, the phrase Zhōngguó or “Middle Kingdom”, i.e. China proper, began to be used in official documents and diplomatic correspondence. “Qing” and “Chinese” are synonymous, interchangeable concepts. Managerial practices and customs of steppe origin are receding into the past with a record speed for such cases. Even the Manchu language, itself a fairly young derivative of Jurchen, is beginning to be rapidly and confidently supplanted by Chinese. In just 2-3 decades, it became, along with the Mongolian, rather a ritual and formal addition to the Chinese original in state acts. In everyday life, it undergoes the most powerful Chinese influence, and is also simply ousted. Long before the Xinhai Revolution, the situation of the Manchu language had become frankly miserable. By the time of the publication of Zakharov’s Complete Manchurian-Russian Dictionary in 1875, the author had already identified the Manchu language as endangered in the preface. During the period of the Japanese puppet regime of Manchukuo in 1931-1945, purposeful attempts were made to revive the literary Manchu language, and on the whole they were unsuccessful – it had been so long and firmly dead. The Manchus immediately began to live in Chinese-made houses (and the emperors in the Forbidden City of Beijing). They began to perceive the Chinese cultural code as their foundations. As early as the middle of the eighteenth century, the Manchus regarded Western nomads such as the Dungans and Uighurs as barbarians, and their Mongols as backwater villagers. In the next 19th century, struggling with the influence of Europeans, the Manchu dynasty would speak of an invasion of foreigners who carried ideas and ways of life alien to the Chinese, from which the Celestial Empire had to be defended, completely ignoring the fact that their predecessors from the Ming dynasty could have said approximately the same thing about the Manchus themselves.

On the other hand, the Manchus did not cease to exist in China as a community until 1912. And not a simple one, but one that has a number of privileges and emphatically demonstrates its dominance. Widely known is the “Manchurian braid” – an official prescription requiring all men of the Celestial Empire to wear a hairstyle of strictly one style: a braid of three strands, which was braided at the back of the head or the top of the head, while the hair at the forehead and on the temples was shaved. A Manchu hairstyle that dates back to old nomadic patterns. Other options crept in with death. It would seem, why such strictness? The authorities explained quite frankly that this is a symbol of obedience.

Forced head shaving

During the conquest campaigns of the 1630s and 1640s, a fairly large number of ethnic Chinese went over to the side of the Qing Empire and served it. And they were recruited into a standard banner military organization, albeit with some reservations. The same was true for the Mongols. By 1642, the Qing war machine consisted of 8 Manchu, 8 Mongol, and 8 Chinese banners – and this remained so as long as the process of subjugation of the Celestial Empire continued. However, by the 1680s, using as a pretext the fact that during a series of rebellions some Chinese units had gone over to the side of the rebels, the government carried out military reform. Henceforth, only the original Manchu banners remain and are considered to be the eight-banner army. It is the people assigned to them who constitute the hereditary warrior caste. All other forces are nominally reduced to the Green Banner Troops, with a fundamentally different legal status and order of service. The Chinese were pulling the strings in many small (up to 1,000 men) garrisons throughout the country. The Manchus of the Banners were half stationed in the capital and half in the other 18 largest cities of the empire. Living an ordinary, private life, they received a regular salary, theoretically on the condition that they were always ready to perform, but in practice it became more and more conditional with each successive generation. By the end of the 18th century, the combat capability of the Eight-Banner Army had radically decreased. By the middle of the 19th century, it was no longer at risk of being sent into battle unless absolutely necessary. By the end of the century, the archaic and utter impotence of this structure as an armed force had become absolutely obvious to all. However, the Banners survived even the Sino-Japanese War and the defeat of the Qing Empire in it. They were liquidated only in 1912 after the revolution. Moreover, all members of the “banners”, regardless of their self-determination, were considered Manchus by the new republican authorities.

Blue Banner Troops in the Middle of the XVIII Century

And this is the essence, the clue to the metamorphosis that has taken place. The Manchus, or rather a part of them, were transformed from an ethnos into a social stratum, a special class. Manchuria, as the region we know today, was at some point in time singled out in the Qing Empire as a kind of imperial domain. It was forbidden to settle there for immigrants from central and southern China, the ethnic Han Chinese. And there the original Manchus have been preserved: speaking the Jurchen language, leading a very simple and poor way of life, although they finally settled on the land, but continue to cultivate many elements of the everyday life of the steppe people. On the other hand, in the main part of China, there were people whose mothers were often Chinese wives and concubines of Manchu fathers, and so on from generation to generation, diluting the original blood more and more. They spoke Chinese, knew (at least the most educated of them) Shih Tzu’s Historical Records, Journey to the West, and could recite a couple of particularly spicy passages from Plum Blossoms in a Golden Vase to their friends. A well-to-do Han Chinese, especially an official, would look the same in a crowd. But at the same time, they remembered that they were Manchus, special people who were not equal to “that.” The duality, increasingly hypocritical as time passed, persisted until the very end of the Empire. Because it was one of its foundations.

Another lesson of the era of conquest, which became one of the systemic foundations of the Qing Empire, is that the interests of the elites take precedence over the needs of the common people, and their main need is to ensure social stability and guarantee the preservation of power and property. Nurhatsi relied on the proto-aristocracy when he needed to break tribal particularism and kurultaino-veche traditions. However, the fruit really ripened later. We remember the story of Wu Sangui. It has a lot of its own nuances. Legend even mixes in a woman, just as in Europe similar stories are woven into the story of the Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. There, King Roderic allegedly raped the beautiful daughter of the Count of Ceuta, who, in retaliation, gave Tariq ibn Ziyad ships to cross. Here, Li Zicheng, who took possession of Beijing, allegedly took a fancy to Wu Sangui’s favorite concubine. But, if we cut off all the superfluous, we will see the following: it turned out to be easier for the Ming general to come to an agreement with the Manchurian prince Dorgon than with the leader of the peasant uprising, even if he managed to proclaim himself emperor. The subsequent history of the Celestial Empire’s confrontation with the conquerors is also full of similar plots. When regional elites were faced with the choice of whether to bow to the Qing Dynasty or fight against it in the same line as grassroots mass movements, they tended to choose the former.

Immediately after the capture of Peking, with the sanction of Dorgon, a special manifesto promised all Chinese officials who went over to the side of the Qing enlistment, promotion, and the opportunity to conduct business together with the Manchus. In the autumn of 1644 the landlords’ retinues regularly went over to the side of the new government. Tough in battle (though not as ruthless as the Mongols of Genghis Khan’s era, for example), the Manchus were very lenient towards those who agreed to fit into the new pyramid of power. It would seem that those who revolt against your enemy in the camp are your allies. However, the Qing administration seems to have forgotten that it had been at war with the Ming Empire in the recent past. Commoners who dared to rise up against their local chiefs were demonstratively punished by it for violating the unshakable hierarchical order. It came to the point of curiosities. Having fought against the Ming dynasty for several decades and continuing to fight against the side branches of the clan holding the south of China in their hands, the Manchus declared themselves… avengers of Emperor Chongzhen who hanged himself! Such Jesuitism should have been unequivocally read and interpreted by contemporaries: retribution falls on the heads of the black people – the former rebels, including those who broke away from Li Zicheng, for the idea, the idea of the possibility of rebelling against the supreme power as such.

From the very first years, in parallel with the banner organization, which, as we remember, would degenerate into a kind of nobility, as well as the old landed aristocracy, the Qing government re-approved the table of official ranks from 9 levels (18 in reality, since each rank was divided into two categories) in two versions – civil and military. Very quickly, a significant part of the former Minsk cadres, supplemented by new ones, formed a large stratum of civil servants and administrators. These three strata, often intertwined with each other, became at the same time the main beneficiaries of Qing society, as well as the pillars of the throne, remaining so until 1912. The military service (and in reality very soon just parasitic) Manchu class of “eight-signs”, regional landowners and administrators, theoretically appointed, but in practice sometimes inheriting their position for many generations, as well as a self-reproducing bureaucracy of “pundits” of Shenshi, who first pass through the general imperial examination, and then gradually rise in rank. Their interests were taken into account by the court in a priority order, and their power was considered indisputable. As for the people, and in particular the peasantry, it was believed that without the support of any of these groups, they simply would not be able to organize themselves to the proper extent. Any rebels can either be crushed by professional armed force or deceived by political maneuvering. In part, these attitudes would persist in the minds of the leaders of the empire until very late – their echo can be clearly heard, for example, in the actions of the government during the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. However, by the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the Banners would simply turn into a tumor on the body of the state, devoid of both power and meaning. The bureaucracy will turn out to be not only corrupt, but, what is much worse, limited in its capacity due to the widespread assertion of mechanism, ritual and servility to superiors, and, most importantly, a self-sufficient structure, which, sometimes interfering in completely petty issues, often did not manage truly large-scale processes in any way, leaving them at the mercy of chance. And the possibilities of the landlords will be seriously undermined.

But this is still a long way off, and in the meantime the Qing Empire has developed and strengthened.

The key participants in the events of 1644 left the historical scene quite quickly. Li Zicheng was killed in battle in 1645, with Chinese on both sides. The powerful Dorgon, who eventually acquired the title of “Regent Father of the Emperor”, died in 1650 at the age of only 38. Even Fulin died very young, only at the age of 22 – in 1661 he was taken away by smallpox. However, he managed to leave an heir – Aisingyoro Xuanye was 7 by the time of his father’s death. He ruled for a long time, until 1722, but, of course, the first and most acute years, the empire was headed by regents.

Aishingyoro Xuanye

At this point, it makes sense to mention the last “birth trauma” associated with the history of the Qing Empire, which seriously affected its attitude towards the sea and everything that comes from it.

The year 1683 is considered to be the date of the end of the Manchu conquest of China – and this is the moment when the state of General Zheng Chenggong and his descendants in Formosa/Taiwan was liquidated. In European historiography, the founder of the Principality of Yanping, however, is better known by another name – Koxinga. The greatest and most formidable of the Eastern pirates. Zheng Chenggong was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Chinese father who was a pirate in the Taiwan Strait. Until the age of seven, he lived with his mother in the Land of the Rising Sun, and then moved to Fujian to live with his father, who received a position in the maritime department of Ming China. Koxinga managed to take his oath to the Ming dynasty before 1644, and then remained firmly loyal to the main line of claimants who ruled the Southern Ming. Zheng Chenggong was quite successful in commanding the flotillas in a number of major river operations, in particular, he won the Battle of the Yangtze, preventing the Manchu troops from crossing and developing an offensive to the south. However, the strategic position of the Southern Ming steadily deteriorated, only to become downright catastrophic by the late 1650s. And then Zheng Chenggong decides to take a desperate step. In an effort to create a base for further operations inaccessible to the enemy, in April 1661 Coxinga (as the Dutch called him) landed on Formosa near present-day Tainan with 25,000 of his men. By this time, the island had been controlled by the Dutch since 1624, who created a trading post and built a number of fortifications. Zheng Chenggong surrounded Fort Zeeland and, after a nine-month siege, starved it to death (by the way, nobly dismissing the defenders after that). Koxinga himself lived only about a year, counting from the victory he won, but already for him he managed to become a legend, and then for almost 20 years his father’s work was continued by his son Zheng Jing. You could say they pirated in the East China Sea and the South China Sea, but that would be too weak. Koxingga did not succeed in evacuating to Taiwan a single representative of the Ming dynasty who had rights to the throne, but this circumstance did not prevent him from declaring loyalty to the former empire and non-recognition of the power of the Manchus. Having declared himself and his descendants regent for the time being, Zheng Chenggong began to make continuous raids on various cities and villages located on the coast. Most importantly, he lent a helping hand, coordinated actions, and, if necessary, helped local rebels escape to the sea. And the effectiveness of his actions turned out to be such that the Qing Empire perceived him as a threat, a full-fledged opponent. The Manchus were unable to build up an equivalent navy, and Koxinga’s mobility, combined with his good knowledge, made it impossible to set a trap for him on land.

Zheng Chengong’s “Sea Power”. Bright red is the territory regularly occupied and held by his troops. Paler are those in which he actively interacted with local rebels.

In the end, the Beijing government imposed the so-called “maritime ban.” In some form, restrictions of this kind have been periodically adopted in China before. In 1371, Emperor Hongwu allowed foreigners to enter the ports of the Middle Kingdom only on the condition that they first presented gifts to the monarch (and thus conditionally recognized their vassalage in the context of Chinese tradition). De facto, this order degenerated over time into a system of official licensing of maritime trade, on the one hand, and on the other hand, gave rise to a kind of auctions of offerings. The Portuguese, for example, were able to essentially buy out exclusive rights in 1567, but later the Dutch (also paying) shook the established monopoly. Now it was much more serious. Not just trade was forbidden, but almost interaction with the sea as such. A huge number of residents of coastal cities and towns were forcibly relocated 15-25 kilometers inland as part of the “sea ban”. At the beginning of the 18th century, the strictures were somewhat relaxed, but the wary and negative attitude of the Qing state machine to any trade and economic contacts through the sea would remain for many years. First of all, because of the suspicion that uncontrollable political trends may come from there. By the age of the Opium Wars, the vast empire’s own maritime trade would be strictly of two kinds: either insignificant or illegal.

However, as mentioned above, at first, the power of the Aishingyoro dynasty was quite steadily strengthening. The Xuanye era was a time of normalization, and the subsequent reign of Aixingyoro Yinzhen (1722-1735, motto/throne name Yongzheng) and especially Aixingyoro Hongli (1735-1799, motto/throne name Qianlong) was the “golden age” of the Qing Empire. And here is a good time to talk about demography and economics.

According to a number of authoritative researchers, at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, Beijing was the largest city in the world in terms of population, with a population ranging from 700,000 to 1,000,000. There were many other cities in the Celestial Empire, which left most European cities far behind. Nevertheless, the vast majority of Chinese lived in rural areas, and agriculture was the undisputed basis of China’s economy. By the end of the 1590s, the population of the Ming Empire before the onset of its systemic crisis was approximately 200 million. This, by the way, is more than twice the number of inhabitants of all the countries of Europe combined. And then a series of troubles began. Internal discord, mass peasant uprisings, accompanied by disruption of the normal course of economic life, and military operations during the period of the Manchu conquest led to the fact that the population of the Celestial Empire fell by almost half, to 100-105 million people! And this is taking into account the inclusion of the new spaces of Manchuria and Mongolia in the Qing Empire format. Then, from the 1680s, the process of restoration begins. By 1724, the subjects of the Golden Clan numbered 130 million, and it was possible to reach the former Ming level and slightly surpass it only in the middle of the 18th century, and partly due to conquests in the west.

Such depopulation, however, had an unexpected positive side: by the end of the 17th century, despite the fact that part of the land was abandoned, the area of arable land per capita had increased to a record. It remained quite high (by Chinese standards) until the end of the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor. Together with the coming of peace, the reboot of the state administration system, as well as the large-scale work begun in the 1680s and 1690s to renovate irrigation canals in central China, these circumstances allowed the country’s economy to grow steadily. With the inclusion of new territories and the increase in the intensity of the use of old ones, new generations of free labor were growing up. One might say “and eaters,” but in general, since the vast majority of people from the new generations were born peasants and worked in agriculture, the additional surplus product they provided outweighed the costs.

And then, as they say, watch your hands. The “Golden Age” of Qianlong, the lasting peace that followed the Western Campaigns of 1751 and 1757-1759 (the Qing Empire undertook military operations against Burma and Vietnam, but they did not require a nationwide effort, and the security of China itself was fully ensured), allowed the Chinese to successfully “breed and multiply” in the second half of the 18th century. In 1766 there were 208 million. In 1812 it was already 361 million, and 20 years later it was almost 400 million. At the same time, the fertility rate remained practically unchanged during the period described, amounting to about 5.8 births per woman, according to modern estimates. There is only one conclusion to be drawn from this: similar to what was happening in Europe around the same time, Qing China was sufficiently developed for the first demographic revolution to begin. Take France. From 1100 until the beginning of the 18th century, its population, with a few notable drawdowns (say, one caused by the Great Plague), hovered around the figure of 20 million. But by 1821, despite the Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonics, there were 31.5 million Frenchmen. Approximately the same thing could be observed in Great Britain and other states of the Old World. In 1798, Thomas Malthus anonymously published his famous “Essay on the Law of Population”, warning that the rate of population growth was outstripping the growth of the production of means of subsistence, which threatened society with disaster.

The Europeans did not fall into the “Malthusian trap” due to the unfolding process of industrialization. The latter solved two problems at once. In the first place, industry has absorbed the labour which would have become superfluous in the countryside due to agrarian overpopulation and the reduction of the size of arable land per person. Hundreds of thousands of people left for the cities and became proletarians, not vagabonds and beggars. Instead of becoming a burden on the economy, it was they who, combined with the power of machines, gave it a new, previously unprecedented acceleration. Secondly, as industry developed, its products made agriculture more intensive and productive. New methods of cultivation, engineering agronomy, and then tractors steamed with chemical fertilizers made it possible to grow much larger volumes of food on the land of the same area. This was the case in Europe. China, on the other hand, jumped to the very bottom of the Malthusian pit…

By the early 1850s, there were 432 million Chinese. The average area of arable land per capita decreases to 1.8 mu. This traditional measure is 1/15 of a hectare. For comparison, the domestic tithe is 1.06 hectares. As a result of the great Peasant Reform of 1861, the average size of the allotment of a peasant who received personal freedom was 3.3 dessiatinas, and this was reasonably considered a very small value. By the beginning of the 20th century, the social tension caused by the shortage of land and the demand for a “black redistribution” had become one of the main prerequisites for the revolutionary explosion of 1905. Yes, the cultivation of rice is more productive than wheat and rye, not to the same extent. Moreover, industrialization was already underway in Russia, albeit at a slower pace than in Western Europe. New sectors of the economy and cities absorbed workers. By 1897, the level of urbanization in the Russian Empire had reached 13%. Very little – in Great Britain it reached almost 40% in the middle of the century. But much more than in the Celestial Empire. Even in 1978, only 17.9% of Chinese would live in cities. The late Qing Empire was a long way from this level. Monstrous agrarian overpopulation led the peasants to impoverishment. In China, there were many poor people and lumpen. And the authorities not only could not help them in any way, but were not even eager to notice and acknowledge the growing crisis. It is here that the social roots of the Taiping Rebellion, the largest and most formidable in the history of the Qing Dynasty and the Celestial Empire in general, are found. The defeat in the Opium Wars only gave an additional impetus to an avalanche that was already ready to break down. 14 years of struggle from 1850 to 1864, 20-30 million died from direct and indirect causes on both sides. But the Taiping did not just promise to create a kingdom of justice and harmony on earth in a purely abstract, religious sense. The insurgents not only smashed government offices, killed all Manchus and high-ranking Chinese officials, as well as those who actively opposed the insurgents. The followers of Hong Xiuquan levied an indemnity on the “rich”, severely punishing those who did not want to pay it, confiscating their property, redistributing it in favor of the poor on egalitarian principles. Unfortunately, such simple (and popular) measures could no longer solve the problems of the Celestial Empire…

In 1996, Samuel Huntington coined the term “Great Divergence.” With it, he outlined the process by which European countries moved forward in development in the modern period, far ahead of the leading states of other parts of the world (in particular Asia), with which they had previously been on a par with, or even lagged behind, the leading states of other parts of the world (in particular Asia). An analysis of the causes of the Great Divergence is beyond the scope of this paper, especially since it is an extremely complex and large-scale issue. Nevertheless, it is necessary to say a few words about this.

It is a well-known fact, which some of our writers are particularly fond of mentioning in the context of criticism of kowtowing to the “West,” that up to the end of the eighteenth century, it was Europe that imported China’s goods, paying for them in silver, and not vice versa. And only then did the treacherous British and French put the Celestial Empire in a dependent position by force of arms and opium poison. Indeed, even in the Age of Enlightenment, Europeans, as a rule, acted as buyers of Chinese products: silk, porcelain, tea, and so on. However, to conclude from this that Europe had nothing to offer China is too bold and simply wrong. First, the Chinese in general – and especially those who were not connected to the top of the state apparatus – simply knew too little about what the Europeans were producing. To put it simply, the level of knowledge of the British, French, Dutch, and Portuguese negotiators about China was immeasurably higher than that of their counterparts about the European states. Secondly, the Qing government was unwilling and unable to organize a large-scale purchase of anything from the Europeans due to its administrative limitations and weakness, and the latter had not yet had the opportunity to impose on the Celestial Empire the intensification of contacts by force (in fact, when it appeared, China was “opened” without asking it much – and the trade balance became fundamentally different).

Finally, but this is the most important thing for us, the predominance of Chinese exports in that era did not mean the superiority of the Celestial Empire in the level of development of productive forces. Both in terms of their technical equipment and in terms of organization. Both silk and porcelain were products of small-scale production. It’s just that there were a lot of producers themselves because of China’s general superiority in population, and the state, or rather the monopolists created by it, organized collective sales.

Omitting many other factors, as well as the nuances of this, which I see as the main and fundamental one, the main reason for the backwardness of the Celestial Empire (and the East in general) is the lack of a social stratum that could integrate equipment (and technology), money and labor into the working capital.

Take, for example, the Qing Empire of the Jiaqing era (1799-1820). It has a large amount of free labor due to progressive agrarian overpopulation. But who could collect and use those hands-free? Landowners, deprived of the opportunity to increase the volume of their main means of production, that is, to expand the area of arable land, willingly got rid of the eaters when they became insolvent. Merchants? But for what? Without sufficient equipment and guaranteed markets for products, such an investment becomes ultra-risky. With a greater or lesser degree of efficiency, the state gathered “superfluous people”, using them, as is sometimes the case now, on infrastructure projects. But, in the first place, these shares were unsystematic, and in the second place, they did not generate capital that exploited wage labor. Further, in the Qing Empire there are a huge number of educated people – “scholars”. Every official is by definition a Shenshi scholar, and he has passed the appropriate examination. But their education is rigidly standardized. Not only does it have a very powerful humanitarian tilt, but it basically takes ritualized forms and often boils down to memorization. Meanwhile, the free intelligentsia has practically died out. Why, if a bureaucratic career is much more profitable? Acting on the instructions of the state, the Shenshi could prepare extensive reference collections-encyclopedias, but who of them could have invented something like a steam engine and for what? To prepare the industrial revolution scientifically and technologically? Even if someone had investigated such matters on his own initiative, there would have been no social demand for the results of such studies. Add to this the powerful censorship, which is constantly looking for sedition. During the reign of the brilliant Qianlong, only the demonstrative burning of undesirable books took place 24 times in 1774-1782. Finally, there were people in China with fairly large sums of money to spare. But they are much more likely to either buy a proven source of wealth with them – land, or use them for understandable trade and intermediary operations than for the intensification of production. For example, from a certain period of time it became very profitable to buy opium in bulk and then resell it at retail…

The Opium Wars are not an episode in the history of European states of which they could be proud. Nevertheless, it should not be thought that the British and the French, who joined them in the second war, carried out some insidious conspiracy, purposefully undermining Chinese society and statehood with the help of drugs. At the time, opium smokehouses were legal in Europe itself, and their clients brought more and more problems over time, which is why the restrictions arose. No. It’s much more prosaic – they just wanted to maximize their profits. And the fact that the opium trade is an extremely profitable business, Europeans in general and the British in particular managed to establish very reliably in the 1820s and 1830s, despite all the prohibitions. Because there were a lot of people who wanted to buy up the smuggled opium for further sale.

Opium ships off Linding Island, China, 1824. Sometimes the goods were reloaded directly into the sea.