There is only one slander from people’s love to hatred. The fate of the “number one therapist” Dmitry Pletnev.

The fate of the doctor Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev (1871?-1941) gives reason to reflect on the strength and weakness of a person caught in the millstones of the punitive system, on the unconditional blind faith of the people in the righteousness of the state. And also about how he would behave if he found himself under the threat of arrest or in Stalin’s torture chambers.

Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev (1871?-1941).

Once upon a time there was a doctor, a good doctor, “therapist number one”

Dmitry Pletnev was born in the Poltava province, in a wealthy noble family. He studied at the Kharkov gymnasium, graduated with honors from the medical faculty of Moscow University, and became a resident at the faculty therapeutic clinic.

At the beginning of 1902, the young doctor received an award of 604 rubles from his alma mater and went to Europe to study foreign clinics. Here are a few excerpts from his letters from that time: “I am currently in Würzburg (Bavaria), working here in the clinic and in the library… It works very well here. Somehow, it is better to argue with your own work when you see people around you who are looking for something in science, and not trying to get rid of the annoying duty called clinical work as soon as possible and get into a tavern”, “Now I am again reading a book and in the clinic – in Munich… I haven’t seen clinics like the one in Munich anywhere, so our Moscow conversation that our clinics are the best in the world comes out only with the usual Moscow boast: “We throw hats at everyone.” One gymnastics department, which we do not have anywhere else in Moscow, costs 40,000 marks; Exactly such a wonderful electrotherapy, light…”

In November 1906, Pletnev brilliantly defended his dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Medicine on heart rhythm disorders and was elected a privat-docent of Moscow University. A year later, he was sent abroad with a university scholarship of 1500 rubles a year to prepare for the professorship, thanks to which he gained experience in the best clinics and laboratories in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Czechoslovakia.

The range of scientific interests of the young researcher expanded, he studied neurotic states, diseases of the digestive system, thyroid gland, and the blood system. Pletnev’s professional authority also grew. Immersion in science did not isolate him from the socio-political processes that were taking place in Russia at that time. For example, he was one of 130 university professors who spoke out against the actions of the police and the Minister of Public Education, Lev Aristidovich Kasso (the “Casso case”), which limited university autonomy in response to student unrest. There was a time in Russia when university professors supported students!

Dismissal due to a conflict with the state did not prevent all of them from quickly finding a decent job. Thus, Pletnev became a professor at the Moscow Higher Women’s Courses. At the same time, he joined the Constitutional Democratic Party (People’s Freedom Party, Cadet Party), headed by historian and publicist Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov.

In March 1917, after the abdication of the Emperor and the transfer of power to the Provisional Government, he returned to Moscow University as a professor and director of the Faculty Therapeutic Clinic. Students loved him. “We were attracted to this brilliant clinician both by his diagnoses and by his sharp and vivid speech. Always elegant, changing his suit every day, not to mention his shirts, perfumed, sparkling with cufflinks, surrounded by pretty women (students, residents), he would enter the auditorium full of some inner strength and begin to speak in absolute silence in a hoarse, rather quiet voice. Pletnev did not resort to pathos. He often stammered, jumping from phrase to phrase, sometimes as if looking for them. But he spoke originally, sincerely and simply. It was easy to listen to him, I even wanted the lecture not to end. His lectures were unexpected and free. It is clear that he had never prepared for them, when he entered the auditorium, he did not know what he was going to talk about and how he was going to talk about them. They were brilliant improvisations. He behaved in the audience like an artist, in the best sense of the word. Like any other person who is accustomed to speaking in public, and with success…“, recalled the future academician A.L. Myasnikov.

Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev was a good doctor, or rather, a talented therapist, as evidenced by the endless queues of people wishing to get an appointment with him. He had the unique ability to accurately diagnose the diagnosis. His contemporaries spoke enthusiastically about his virtuoso diagnosis of coronary thrombosis, about his studies of cardiac aneurysms and heart failure.

Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev (1871?-1941) with colleagues. Source: Yandex Images

Proof of his highest professionalism is at least the fact that his colleagues, in case of their own illness, turned only to him for help. Pletnev treated Krupskaya, Lenin, and Academician I.P. Pavlov. At Lenin’s request, he went to Dmitrov to consult the sick Pyotr Kropotkin. He flew to Iran at the request of the Shah to help one of his family members. It is no coincidence that in the late 1920s he became a full-time consultant to the Kremlin’s Medical and Sanitary Department and the First Communist Hospital.

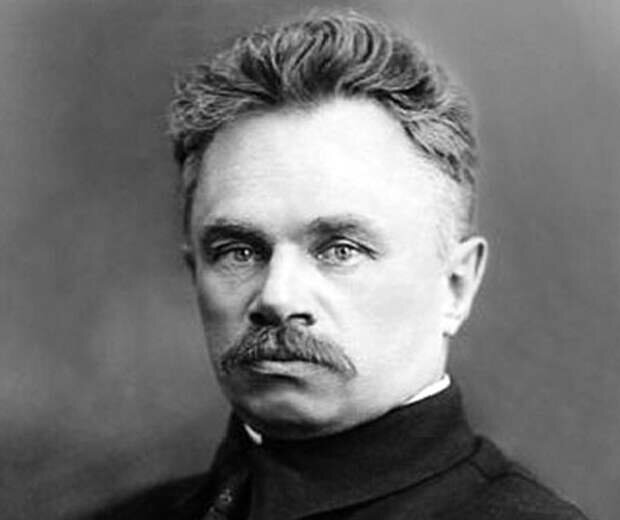

Authority and respect also have a downside: the envy of colleagues, the dissatisfaction of superiors, the resentment of patients. As you know, you can’t please everyone and you won’t be nice to everyone. Pletnev had disagreements with the rector of Moscow University, Andrei Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky, about whom he allowed himself to make prickly jokes. Apparently, while working, Pletnev did not notice that the situation with free thought in the country had changed dramatically, the time had come when it was necessary either to keep one’s mouth shut or to support the party line.

In 1929, a series of articles criticizing the old intelligentsia was published in the press. It has been written, for example, that “the bourgeois professor and sectarian in all varieties become echoes of the Nepman and the kulak.” In response to the publications, the so-called purge of the Soviet apparatus was launched, and special commissions were set up in the institutions. Pletnev was warned about the upcoming meeting of one of them, which he had to attend, but instead the professor left to give lectures in Voronezh. The lectures were a great success, but on his return Pletnev was fired. “Pletnev, intoxicated with his imaginary fame and confident in the strength of his ‘connections’, challenged the entire public of the faculty and refused to appear at the public review. Outraged by Pletnev’s behavior, professors, students and public organizations of the Faculty of Medicine demanded that he be removed from the leadership of the department,” wrote D.G. Oppenheim, director of the 1st Moscow Medical Institute, a few years later, recalling the events of 1929.

But the authority of Dmitry Pletnev was then stronger than the capabilities of Rector Vyshinsky. Pletnev continued to hold senior positions in several medical institutions. He was successfully engaged in scientific work and practiced. The apogee of his fame was 1933 – the 35th anniversary of his medical, scientific and pedagogical activities. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR adopted a resolution awarding him the title of Honored Scientist. The journal “Clinical Medicine” devoted a separate issue to this event with laudatory articles by the country’s leading doctors, scientists from Germany, France, and Czechoslovakia. The 9th therapeutic building of the Moscow Regional Clinical Institute was expanded, re-equipped and named after the hero of the day. The press called Dmitry Pletnev “a shock worker of the health care front”, “an enthusiast of Soviet medicine”, “the world’s greatest authority in the field of clinical medicine”, “the number one therapist”.

Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev (1871?-1941).

Tragedy in Three Acts: Slander, Self-Incrimination, Reprisal

In the summer of 1934, Professor Pletnev found himself in an unpleasant situation. A former patient came to him with the accusation that he allegedly bit her breasts, which caused her to develop mastitis, she lost her ability to work and experienced emotional turmoil.

Initially, Professor Pletnev treated the claim of citizen B. as the extortion of an inadequate woman and tried to get rid of her with money. But when the blackmail intensified, he appealed to the police with statements dated December 29, 1936 and March 12, 1937. In them, he indicated that the woman had called his daughter’s home with threats to go to the Therapeutic Society with a complaint, not to allow him to travel abroad. Citizen B. literally harassed Pletnev, accused him publicly in public places. Finally, the story made it to the newspaper.

On June 8, 1937, Pravda published an unsigned article titled “The Professor is a Rapist, a Sadist.” The article quoted a “stunning human document” – a letter from citizen B: “Damn you, criminal who has abused my body! Damn you, sadist who has used his vile perversions on me. Damn you, you dastardly criminal who has bestowed upon me an incurable disease that has disfigured my body. Let shame and humiliation fall upon you, let horror and sorrow, weeping and wailing be your lot, as they have been mine since you, the criminal professor, made me the victim of your sexual promiscuity and criminal perversions. I curse you.”

The article ended with a call to action: “Soviet doctors and our entire public, no doubt, will pronounce their harsh sentence on a criminal who has abused the trust of a citizen who hoped to see a human being in a doctor, but saw a beast, a sadist, a rapist.”

Immediately after the publication of this article, emergency meetings of the All-Russian and Moscow Therapeutic Societies, meetings of the collectives of research and educational institutes, hospitals and other institutions were held. They passed resolutions stigmatizing the “number one therapist” to whom these same people had recently sung their praises. Among the accusers were the voices of both peers and younger colleagues of the professor. Half of them will hear the same epithets “beasts and sadists” addressed to them in 1952 in the “Doctors’ Case”.

On June 9, 1937, the day after the publication of the article, the Prosecutor of the USSR, A.Y. Vyshinsky, ordered to begin checking the “facts” set forth in Pravda. And on July 17-18, the trial took place. At the request of the parties, the case was heard behind closed doors. The court found it proved that on July 17, 1934, the defendant Pletnev tried to rape his patient in his doctor’s office. Pletnev was found guilty under Articles 19-153 of the Criminal Code and sentenced to two years in prison. Taking into account Pletnev’s recognition of the gravity and immorality of his actions, the sentence was declared conditional. In conversations with his relatives and friends, Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev explained that he did not make any confessions at the trial. The professor was 66 years old.

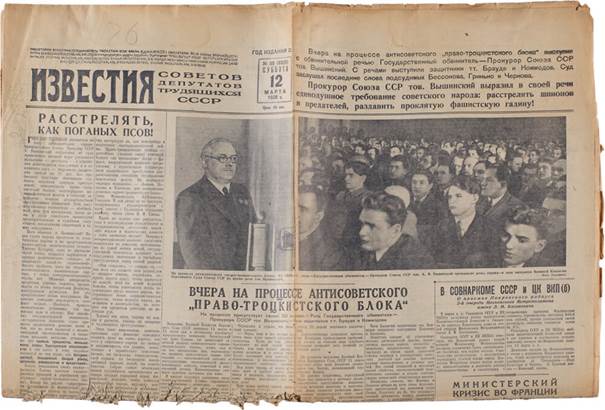

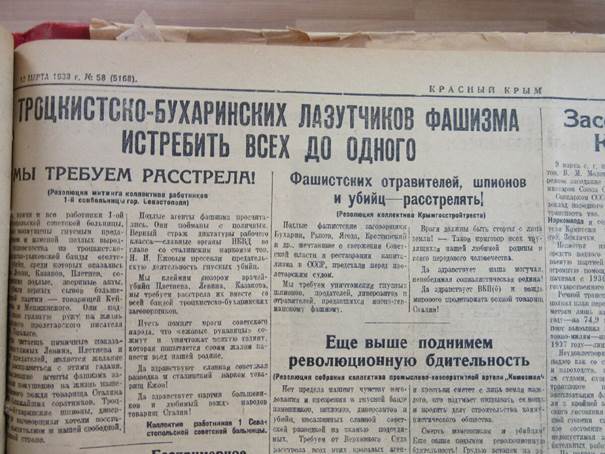

The people unanimously support the decision to shoot “enemies of the people” during the years of the Great Terror. Source: Yandex Images

Half a century later, Literaturnaya Gazeta wrote about this story. In response to the publication, a letter about citizen B. came from her former flatmate: “… there was such a house on Arbat No. 56/36 … On the 2nd floor, our neighbor (common wall) was the journalist Braude (I don’t remember her name and patronymic). She was tried as “citizen B.” She was mentally ill (schizophrenia with delusions of persecution). When she left the apartment, she would take matches, cut paper, wrap each match in a piece of paper, and close the entire door tightly around the perimeter of the door. We kids watched her do it, and after she left, we pulled out matches. Every day there were police, sometimes with shepherd dogs. She sued endlessly. One of the reasons for breaking into her room was a crack in the ceiling in the wall, through which “my grandmother would get into it and take something there.” It was impossible to take her to a mental hospital. The police had to protect her from thieves and comply with her demands.” Apparently, the police protected her as a witness in a criminal case.

Professor Y.L. Rapoport told about citizen B.: “Her appearance did not evoke any sexual emotions and was not even associated with such a possibility. She was a woman of about forty, with a remarkably unattractive and unpleasant appearance. A long, shabby skirt, worn-out heels; above average height, greasy-looking brunette, with unkempt braids of poorly combed hair; A plump, swarthy face with thick lips. The mere sight of her made me want to be free of her presence as soon as possible. And suddenly it turned out that she was Mrs. B., the virgin victim of the lust of Professor P., “the rapist, the sadist!” When I learned of this, I said that she could only be bitten in self-defense, when other means of self-defense against her had been exhausted or were inaccessible.

The absurd criminal case against the best therapist in the USSR, which ended with a suspended sentence, was aimed at dishonoring the outstanding scientist and doctor. The final massacre was yet to come.

In the autumn of 1937, just two months after the trial, Dmitri Dmitrievich Pletnev was arrested in the case of the anti-Soviet Right-Trotskyite (Bukharin) bloc and accused of murdering V. V. Kuibyshev and M. Gorky. In 1938, he was a defendant at the Third Moscow Trial.

The Soviet press reports on the trial of the bloc of Rights and Trotskyites. “Izvestia” for March 12, 1938. Source: Yandex Images

An excerpt from Pletnev’s interrogation on March 9, 1938 at the morning session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR:

VYSHINSKY: What was the formation of the plan which you and Levin worked out with regard to the murder of Alexei Maximovich Gorky? Keep it concise.

Pletnev: To tire out the organism and thereby lower its resistance.

VYSHINSKY: So much…

Pletnev: So that it doesn’t be… In a word, to reduce resistance, to make sure that the body cannot resist.

VYSHINSKY: To reduce it to the limit?

Pletnev: Yes.

VYSHINSKY: To the extent possible?

Pletnev: Yes.

VYSHINSKY: To the limit that is possible and accessible to human forces?

Pletnev: Yes.

VYSHINSKY: To take advantage of this state of a weakened organism for what purpose?

Pletnev: For a possible cold and a cold-related infection.

VYSHINSKY: That is, to deliberately create an atmosphere of inevitable illness with some disease?

Pletnev: Yes.

VYSHINSKY: And take advantage of the illness to do something?

Pletnev: To apply the wrong method of treatment.

VYSHINSKY: For what?

Pletnev: To kill Gorky.

On the same day, the conclusion of the medical examination was announced. Experts came to the unanimous conclusion that Gorky’s method of treatment was deliberately sabotage, aimed at hastening his death.

The staff of the Sevastopol hospital stigmatizes and demands that the murderous doctors Pletnev, Levin, and Kazakov be shot. Source: Yandex Images

In his last speech, Pletnev repented of “his criminal activities” and asked for leniency: “If the court finds a way to save my life, I will give it completely and entirely to the Soviet Motherland, the only country in the world where labor in all its branches is guaranteed such an honorable and glorious place as nowhere else and has never been.”

The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced D.D. Pletnev to 25 years of imprisonment with loss of political rights for five years after serving the prison sentence with confiscation of his personal property. Pletnev’s wife was sent into exile to Kostroma, where she remained until 1944, when she died in January 1945.

While serving his sentence in the prison of the city of Zlatoust in the Chelyabinsk region, and from the summer of 1939 in the Oryol region, Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev wrote letters to Beria, Vyshinsky, and Voroshilov:

“The whole indictment against me is a falsification. Through violence and deception, I was forced to confess, interrogations for 15-18 hours in a row, forced insomnia, suffocation by the throat, threats of beating led me to a mental disorder when I did not give a clear account of what I had done…”

“I have been sentenced in the Bukharin case to 25 years, i.e., in fact, to life imprisonment in a prison grave, … I was subjected to horrific swearing, threats of the death penalty, dragging by the scruff of the neck, suffocation by the throat, torture by lack of sleep, sleeping for 2-3 hours a day for five weeks, threats to tear out my throat and with it a confession, threats of beating with a rubber truncheon… By all this I was brought to the point of paralysis of half my body…”

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Pletnev was held in the Oryol prison. When the Germans approached Orel, all the criminals were sent to more distant camps, and the political ones were left behind. On September 8, 1941, Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev was sentenced to death “for anti-Soviet agitation and dissemination of slanderous fabrications in the Oryol prison.” The shooting was carried out on September 11 by NKVD officers in the Medvedev Forest, located north of Oryol. Pletnev was executed among 157 prominent statesmen, party and scientific figures, for example, Maria Spiridonova, the leader of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, the diplomat H. G. Rakovsky, O. D. Kameneva, Trotsky’s sister, and others. The execution was initiated by the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR L. P. Beria and sanctioned by the State Defense Committee of the USSR headed by I. V. Stalin.

Memorial in the Medvedev Forest, the city of Oryol.

In 1985, the Supreme Court of the USSR dismissed the criminal case against Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev and fully rehabilitated him.

Sources: V.I. Borodulin, V.D. Topolyansky. Dmitry Dmitrievich Pletnev. Voprosy istorii, No. 9, 1989