The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in German Propaganda

Late August-December 1939: Propaganda before the Winter War

From the Regime to Facebook: The Propaganda Apparatus and the Pact

On August 20, journalists received information about the conclusion of a “German-Russian” economic agreement. This should have been commented on cautiously, pointing out that the two countries complemented each other with their economies “in the most natural way” [PA, Nr.2834, PA, Nr. 2835]. The real bombshell exploded two days later: the announcement of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact. This was to be published on the front page, in accordance with the instructions given, describing it as a sensational turn in the history of the two peoples, who again “found each other.”

It was desirable to make references to the time of Bismarck, and it was even allowed to mention the “Treaty of Rapallo”. The press was also allowed to hint that Russia and Germany would be able to resolve all open issues in Eastern Europe on their own.

The fact that the pact was concluded with the Soviet Union, and not with pre-revolutionary Russia, was avoided. At the press conference, when the instructions for the press were announced, it was emphasized that it was impossible to mention the problems of the worldview between Communism and National Socialism. It has been said that “the German people have an understanding of the differences between the two political systems.” And when Braun von Stumm, who read out the proclamation of the pact, uttered the phrase about “long-term cooperation,” the audience burst into laughter, as the journalist Fritz Sanger, who was present, wrote. Fritzsche, the head of the press conference, tried to salvage the situation, calling the laughter a sign of “joy at the new pact.”

The long history of cooperation between Germany and Russia was erased in the minds of Germans by the negative image of the Soviet Union, created for many years by the propaganda of the Reich. Naturally, journalists could not readjust in one day, so the next day the Ministry of Propaganda issued another instruction, demanding more “correctness and warmth of expression.” Many propagandists themselves were perplexed, and many were angry, for example, the ardent anti-Bolshevik Alfred Rosenberg.

Apparently, there were already rumors among journalists about the future partition of Poland, so the Ministry of Propaganda decided to make public information about the existence of secret agreements with the Soviet Union, according to which the future border would be drawn. The arrangements themselves were, of course, a secret and were not revealed [see BAK, ZSg. 101/14/52, 17.9.1939].

In the official joint German-Soviet declaration of September 18, it was stated that the invasion of Soviet troops would take place by mutual consent for the purpose of restoring order and tranquillity in Poland. These actions are carried out in accordance with the non-aggression pact [see FB 19.09.1939].

The press had no doubts about the finality of the decision to rapprochement between the USSR and Germany. Even Hitler himself said that it was “the final turning point in the history of the two peoples” [see FB 02.09.1939].

The Ministry of Propaganda planned to involve the Soviet press in the assertion that the war had in fact been provoked by England. Its own press was to propagandistically support the entry of the Soviet army into eastern Poland [BAK, ZSg. 109/3/105]. Later, it was planned to give positive comments about the pacts forced by the Baltic states.

Even with the growing tension in Soviet-Finnish relations, German propagandists demonstrated foreign policy unity with the USSR. That not everything was so good in terms of foreign policy reached the propagandists only with the beginning of the Soviet-Finnish war. A press conference on this issue did not bring clarity. There were no instructions about changing the course towards the USSR, but the sympathies of the journalists were unequivocally on the side of the Finns. German soldiers had already fought in Finland in the past as part of the Freikorps, even some of the journalists present. Many had friends among the Finns [BAK, ZSg 102/20/378, 5.12.1939].

Internal development of the Soviet Union:

A carefree look at new friends?

Although the pact with the USSR could be presented in foreign policy as a “blow to the Encirclement” and an attempt to avoid a major European war, it was difficult to explain that the anti-Semitic German government had concluded a pact with the “Jewish clique.” Propagandists could explain this development by the change of power in the USSR, the removal of the “Jewish Bolsheviks.” But to do this, you had to have some knowledge of what was happening there. And none of the FB journalists has really studied what is happening in the Soviet Union in recent years. For propaganda articles, it was always possible to invent, for example, another famine, an uprising or a shooting. Now, after the conclusion of the pact, the propagandists simply had nothing to write about the USSR. In September, we still managed to scrape together 11 articles, but from October to December only three short notes on the internal development of the U.S.S.R. were published.

The topics of these publications mainly described the economy of the USSR, since an increase in trade between it and Germany was expected. The Soviet Union had to supply Germany with a huge amount of goods. Statements made six months ago that chaos reigned in the Soviet Union have sunk into oblivion. “Economic experts” now argued that the Soviet Union could supply Germany and that the opportunities for trade were “virtually unlimited.” The propagandists did not even try to explain the amazing transformation from a “poor country”, as FB had previously assured, to a “rich state”.

This is how it was written about the oil program of the Soviet Union [FB 03.10.1939] and about “The Riches of Russia” [FB 05.10.1939], even with the citation of Soviet sources, describing the growth of agriculture, mining and energy supply. The author of the article also wrote that Russia would supply Germany with a million tons of fodder for livestock, which in fact was not true, since trade negotiations were carried out for a long time without success and the number of one million tons was greatly exaggerated. In the FB of 18.11.1939 it was written about new oil fields in the Crimea.

But in some of the published articles, one could feel the protest of the FB editorial board against the concluded pact. One article [FB 03.09.1939] is about the capture of Moscow by Napoleon, the other is about a French film in which Polish conspirators tried to depose the Russian Tsarina, the “German” Catherine the Great and replace her sister, with the majestic surname – Elizabeth Tarakanova.

A fatter hint appeared in another article [FB 19.09.1939], a critique of the “Russian Memoirs” by Sophie von Burghöveds. The author, Prof. Adolf Bartels, concluded the article with the following words: “First the war… then the Revolution of 1917… Suddenly, like an earthquake, it broke out in a few days and demolished everything that had been built for centuries. I was a witness to the terrible mortal struggle of tsarism. He witnessed the terrible imprisonment of the royal family in deep Siberia and the Yekaterinburg tragedy. I was a witness to all this, and it is with sadness that I close my book of Russian memoirs.” Obviously, the author skillfully played on the reader’s feelings, who, of course, could not have witnessed the execution of the royal family. And the revolution in Russia had been brewing for many decades and broke out as early as 1905, and not unexpectedly in a few days. Needless to say, if the author does not even distinguish between the bourgeois February Revolution, during which the Tsar and his family were removed and arrested, and the October Revolution. And he could not have known that the subsequent destruction in Russia was caused mainly by the civil war, which was unleashed rather by the White forces, which the author of the article mistakenly calls tsarism, with the help of the Czechoslovak corps.

In October, the Ministry of Propaganda indicated that all articles on the Soviet Union must be submitted for approval before publication. Thus, it was possible to prevent similar articles in the future. Historical articles about Russia have come to naught, as have other publications on internal development in the USSR. And even telegrams from Hitler and Ribbentrop congratulating Stalin on his birthday were simply printed on Facebook, leaving no comment.

Soviet-German Relations: The Shock of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

In fact, the propagandists did not invent a new picture of the Soviet Union. Therefore, for the German philistine, it remained generally the same as before the conclusion of the pact, filled for years with propaganda fabrications that had nothing in common with the real conditions of life in the USSR. Therefore, the average German man in the street could not think anything good about the Soviet Union. And German propaganda was in no hurry to change this state.

In promulgating the “German Trade and Credit Agreement with the Soviet Union,” the FB made its job easier by printing instructions for the press almost word for word in the form of an article: The two countries complement each other in a natural way with their national economies. The agreement is in line with the German trade policy, which seeks good trade relations with all countries, complementing Germany economically [PA, Nr. 2835, ZSg. 102/18/389/11].

On August 23, Seibert’s article on the pact itself was published, immediately under the article “Poland is pulling the army to the border.” Seibert wrote, in accordance with his instructions, that Germany was making honest treaties instead of surrounding others, and that the natural state of the two peoples, interrupted in history only for a short time, had been restored. He made references to the time of Bismarck.

Next, Seibert ventured to cross the prescribed boundaries. He wrote that the pact was primarily directed against the “reactionary imperialism of the democracies” and that Britain’s attempts to draw closer to the U.S.S.R. had now failed because of entirely different interests.

Apparently, in the past, Seibert was a follower of National Bolshevik ideas, which he now readily began to pour out in his publications. He wrote of the “young socialist nations” that had created a new law on the European continent. The British people do not really know that they are really fighting for reactionary capital, mistakenly considering it a struggle for Poland and democracy [FB 27.08.1939].

In this way, Seibert described a picture of a world in which Germany and the USSR worked together against capital, and the pact was a kind of triumph of the German and Russian nation against capitalism.

Such a worldview led to the growth of pro-Soviet sentiments in Germany, which the Ministry of Propaganda, as well as the German government, did not want.

Despite the signing of the pact, all those who made the effort to do so were more restrained in their statements. In some Facebook publications, iconic gestures were felt, such as the photo of Stalin laughing next to German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop at the signing of the pact. But in their speeches, Ribbentrop himself, Molotov, and Hitler stressed that there were still differences in the worldview of the two countries. At the moment, however, they did not interfere with the rapprochement.

Hitler noted that he saw no reason for hostility if the USSR did not export its doctrine. At the same time, Molotov did not consider “the divergence of worldviews to be an obstacle to the establishment of good political relations.”

But how did it come to be the most ardent builder of common ideological traits between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union? Part of the answer comes from the speeches of the politicians themselves, who took part in the formation of the pact. Thus Molotov, Ribbentrop and Hitler agreed that the pact was final. Hitler even went so far as to declare that “any future use of force is out of the question” [FB 02.09.1939].

Fritzsche, the host of the press conference on August 23, also declared: “Every journalist must understand that this is not a tactical maneuver. There has been a historic turn in the true sense.” For this reason, “warmth of expression and precision” are important in publications [PA, Nr. 2870, ZSg. 102/18/398].

The staff of the FB, the “militant newspaper of the National Socialists,” considered it their task to clarify questions of worldview and therefore did not follow the instruction to abstain. The reader should have had no doubt that the pact was final and irrevocable.

The outbreak of war in September 1939 did not change anything in this respect. Moreover, it was forbidden to openly call the war a war. And Facebook especially strongly emphasized Moscow’s support for the war with Poland, quoting Soviet newspapers. For example, on September 8 there was an article entitled “The Capture of Cracow Attracted Much Attention in Moscow,” and on September 16 an article in the newspaper Izvestia was quoted about the encirclement of 250,000 Poles. An article on September 13 described how Germany and Russia were restoring order in Poland, and quoted Pravda: “The prison of nations has collapsed like a house of cards.” Such selective quotations from Soviet newspapers were intended to give Hitler’s own statements greater persuasive force.

The Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland was described by Facebook in publications as actions not directed against Germany and as not contradicting the signed pact. In approximately the same words, FB commented on the established demarcation line on September 23, the exchange of instruments of ratification to the “Moscow Agreement” and, now, the final delimitation of its interests. It is also noteworthy that German and Soviet troops passed through Brest-Litovsk on the front page of Facebook on September 25. All this was to show how unshakable German-Soviet relations are now.

Anti-Comintern Propaganda and Deceived Allies

In August 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was openly rejected by the press of the states participating in the Anti-Comintern Pact. After the news of the German-Soviet agreements on Poland and the Baltic states became known, there was widespread indignation in Italy behind closed doors and in the press. During the Winter War, Italian politics and the press were clearly on the side of Finland, and even emphasized Germany’s responsibility for Finland’s tragic fate.

In Tokyo, the German pact with Moscow was regarded as treason from the very beginning, especially since a secret supplementary agreement to the Anti-Comintern Treaty forbade both governments to take such a step. The shock of the pact was so great that it led to an internal political crisis and the resignation of the government in Tokyo.

FB made no mention of the unrest caused by the pact. On the other hand, the pact paved the way for a Japanese-Soviet rapprochement and the conclusion of an armistice in September 1939, which served the interests of the militarily weaker Japanese. The FB later commented on these events in detail, using as evidence the contribution of the German-Soviet pact to the resolution of international conflicts [see Krebs].

Quoting the press from Italy, Spain, Japan and Hungary, FB created the appearance of support for Germany’s new policy on the part of these countries. Vague wording obscured the fact that there was no real support for the pact on the part of Germany’s allies. In particular, the reaction of Japan and Spain was restrained. FB only wrote that “Japan’s position has not changed.” In an article on Spain, the author tried to prove that the Spanish press called the pact “a victory for German diplomacy.” In the author’s opinion, only Germany could survive the rapprochement with the USSR without harm to itself, after it defeated Bolshevism by defeating it in Spain. Of course, it was clear to everyone that few people could be convinced by such arguments, so they simply moved on to the topic of the common German-Spanish struggle against the democracies.

There was hardly a single country in which the pact was welcomed. FB could only write that the pact made a “strong impression”. The subject of the Anti-Comintern Pact was to be gradually “buried” from August 24 onwards. And after the attack on Poland, it was important to show that many countries welcomed this action by Germany and later the Soviet Union. Moreover, neutrality was presented by propagandists as support.

Neither the articles about Spain nor Italy said that their attitude had changed. In any case, it did not follow from the reports that after the Soviet intervention in Poland, the mood against Germany’s deceitful policy had changed there as well.

By pulling Japan along, propaganda built a common front against democracies. When the Japanese government once made a scathing remark against England, the FB even issued an editorial on the subject, underlined in red. It is true that the conflicts between Japan and the Soviet Union, which was an ally of Germany, could not be completely ignored. However, every step on the road to understanding was extolled, and a possible settlement was presented as a positive consequence of the German-Soviet pact in propaganda.

Encirclement Propaganda: The Alienation of the Soviets and the Western Powers

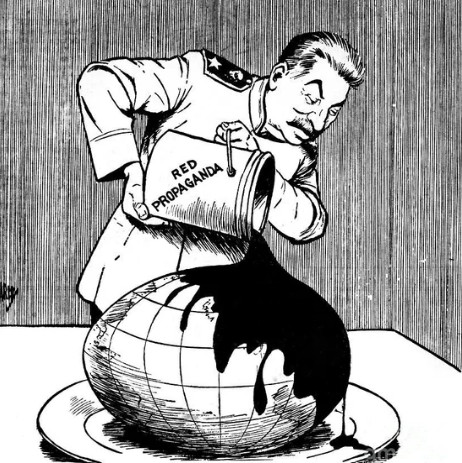

After the pact was concluded and the subject of the anti-Comintern disappeared from the press, propaganda found a new enemy – the “Plutocracy” – mainly in the person of Great Britain. The shifting of the blame for the future war onto her had already begun before the conclusion of the pact, and after the accusations intensified: the countries “surrounding” Germany, i.e., England and France, were in fact the warmongers.

FB wrote that Stalin was wise not to allow the “Jewish” agitators in London to draw him into the anti-German coalition, as they had done with Tsarist Russia during the First World War. In this way, the “propaganda war against the West” replaced the propaganda against the East, and the attribute “Jewish” was freed from the term “Bolshevism” and attached to “international Freemasonry.” This was also the essence of the ideological argument: in the final analysis, the “Jews” were still to blame, only they had mysteriously moved the “headquarters of the enemy of the Reich” from Moscow to London.

Thus Fritz Nonnenbruch wrote in an article of September 8 that “the Germans do not hate the English people, but the Jewish-Masonic, democratic-capitalist clique which has driven the English into this war against us.” Seibert wrote on September 9 about a “Jewish-Masonic world conspiracy” of which the English people knew nothing (but Seibert apparently found out somehow) and, thinking that they were fighting for Poland and democracy, the British were actually paying in blood for reactionary capitalism to make a profit.

Koppen wrote in a Facebook article on April 17 of the same year that “the propaganda headquarters of the world’s enemy number 1 is located in Moscow.” And now, on September 6, London was called “the headquarters of the world’s lies.” And on September 26, Seibert relayed Hitler’s words in Danzig through an article: “The Germans and the Russians will never tear each other apart for the British puppet masters, and will not allow them to interfere in the questions of the East.”

In this way, the war against Poland was justified as the result of the “encirclement of Germany,” the “Jewish warmongering” in the international press, which eventually pushed the Poles to their intransigent policy. As part of this anti-Western press campaign, the Soviet Union played an important role for Germany by allegedly confirming the theses of German propaganda. The press of the Soviet Union allegedly ridiculed the British warmongering and directly named those responsible for it. Thus, the Soviet Union served to ensure the security of Germany, because the Fuehrer eliminated the real danger of British intervention by concluding an alliance with the Soviet Union [FB 08/09/22/25.10.1939].

The innumerable contradictions arising from this line of reasoning could not be resolved by the propagandists: how, for example, could it happen that the formerly “exterminatory,” militant Soviet Union, now stood for peace? How could it happen that the “headquarters of the world Jewish conspiracy” suddenly found itself in London and not in Moscow? All these questions remained unanswered, while anti-British and anti-French campaigns in the press steadily intensified until the end of the year.

Press campaign against Poland:

“The Polish state ceased to exist”

The anti-Polish campaign in the press was also controversial. However, it was preceded by a longer preparation, during which Poland’s former friend in propaganda turned into a contemptible enemy of Germany. The pact concluded with the USSR simply led to the final “exaggeration of Poland’s tone.”

Reports about Poland flooded the pages of Facebook after the announcement of the signing of the German-Soviet Pact. Important topics were the “Polish attacks” on the Germans, the oppression of minorities in Poland (Germans, but also Ukrainians, Slovaks and, more recently, even the Czechs), the territorial claims of the Poles against Germany, Polish “arrogance”, the lack of culture of the Poles, and Danzig, which had always been a German city and therefore should be returned to the Reich.

Propaganda wrote that Poland was allegedly concentrating troops on the borders. Theodor Seibert, in his first comment on the pact of August 23, wrote that it must now dawn on the Poles that the democracies had done them a disservice with their guarantees. A Facebook journalist from London wrote on the same day that they were already preparing for the rapid development of German-Polish relations. The next day, a London FB reporter mockingly quoted a Labour MP who remarked that defending Poland without Russia would be very difficult for England. On his own behalf, the reporter added that Hitler would now become the undisputed master of continental Europe.

With such statements, the reporters went far beyond what was permissible in instructions for the press. They allowed only a slight hint of possible developments [PA, Nr.2911, ZSg. ZSg 102/18/404/(1)]. But the wording was again too lengthy and contradictory for journalists to find loopholes and opportunities in contradictions.

Thus, Theodor Seibert wrote on August 25 that the Poles were now trapped in panic terror and senseless rage between the mighty walls of their neighbors to the East and the West. In so doing, he merely expressed what was already clear from the anti-Polish hype produced by German propaganda, without violating the instructions.

With the outbreak of the war, few indications about the position of the Soviet Union made it to the press. On September 10, the FB reported on the mobilization and concentration of troops, but presented them as national defense measures due to the uncertainty of the situation in Poland. In preparing press reports on the Soviet intervention in Poland, FB wrote on September 11 that the Polish government was planning to escape through Romania and that the Soviet press was reporting chaos and disorder in eastern Poland, and on September 14 of violations of the Soviet border by Polish aircraft. This was the initial pretext for the USSR’s intervention.

Identification of areas of interest

As described above, propaganda prepared German public opinion for war with Poland, arguing with imaginary attacks on German minorities, Polish chauvinism, the threat of “encirclement” of Germany (which made the German attack preemptive), and the final elimination of the “Treaty of Versailles.” All this justified the attack on Poland in the eyes of the citizens. At the same time, the topic of “Lebensraum in the East” and anti-Semitism against Polish Jews were not mentioned directly. Thus, the attack on Poland had to look justified in the eyes of the whole world.

But the entry of the USSR into Poland from the east created an insoluble problem for the propagandists. Presenting Germany as a liberating country, propaganda could not present the USSR in the same vein. After all, until April 1939, all the propaganda told the Germans about the oppression of Ukrainians and Russians in the USSR. Therefore, it would be illogical and even foolish for the Soviet Union to suddenly liberate the Poles. It would also be illogical to tell readers that the USSR had to enter Poland in order to restore order there, since for months and years before that, ordinary people were told that it was in the Soviet Union that chaos reigned.

But it was precisely these two arguments that the Soviet government itself used to invade Poland. That is why the official Soviet communiqué on the invasion said that the Soviet Union was invading Poland in order to liberate the fraternal peoples of Belarus and Ukrainians. For example, Facebook had no choice but to write about the former “destroyer of nations” the Soviet Union as a country in which people suddenly became concerned about national minorities.

Seibert wrote about it on September 18 on Facebook as follows:

“For many years, the whole world was well aware that Polish chauvinism oppressed not only the large German population in western Poland, but also the Belarusian population in the northeast, as well as Ukrainians, and infringed on their national, political and economic rights.

The founders of this state drew the border in the east after the Soviet-Polish war in 1920, which was a mockery of nationalities, and which the Soviet Union only tolerated, gritting its teeth, but never recognized it. We wholeheartedly welcome Moscow’s decision, which, as the Soviet Government’s note to foreign powers shows, is based on blood ties between the peoples of eastern Poland and the neighboring federative republics of Byelorussia and the Ukraine. In Eastern Europe, too, clear and lasting conditions must be created once and for all, just as they were created in Central Europe by the energy of the Fuehrer in the fateful years of 1938 and 1939. But the new National Socialist Reich is of the opinion that peace and tranquillity can be restored only when the borders are drawn according to the law of blood and soil.

This argument with the notorious law of blood and soil was immediately taken up by all propagandists and subsequently cited many times. Nationalist-minded citizens, reading this, apparently understood what was meant by this law. And although it was not possible to get rid of the contradictions to the previous reports about the USSR in this way, at least they tried to explain what is happening now with this law:

Eastern Europe was to be divided into two “cultural regions,” Russian and German, in which foreign powers were not to interfere (meaning England in particular). The “unraveling of ethnoses” had to be carried out, so Germany was not interested in Eastern Poland, which was inhabited mainly by Slavic peoples [FB 11.10.1939]. In Seibert’s opinion, this “unraveling” included the resettlement of Baltic Germans, as well as Germans from the USSR and their settlement of new lands taken from Poland. Alfred Rosenberg added that the Baltic Germans would thus be able to carry out their historic task as a “German fortress” for defense against the east.

In general, there were many articles about good joint work and a lot was written about the fact that soon Germans from Belarus and Ukraine would be resettled in Germany. These settlers were called “pioneers of the culture of the German nationalities”, who would now be given a new task in “Adolf Hitler’s Greater Germany” [FB 11.12.1939].

Increasingly, the Soviet Union was referred to as Russia in the press. On the one hand, the designation Russia could be combined with new, somewhat “modern” popular racist arguments (i.e., Russia is a Russian “nation-state” instead of an international USSR), on the other hand, journalists sometimes alluded to the times before the First World War and the Russian Revolution, when Germany, Russia and Austria divided Poland.

For example, on September 19, FB published an article entitled “Russian Army Reports” about the rapid advance of Soviet troops in Poland. After the outbreak of the Soviet-Finnish war, FB published “Russian Army Reports”. Along with the name Russia, the terms “Soviet Russia”, “Soviet Union”, “Soviet” and “Soviet-Russian” were also used. And once, in a text about the delimitation of the new borders of the USSR and Germany, it was written about “two Reichs”, although the term “Reich” seemed to have been reserved only for Germany. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, on the other hand, was constantly referred to as the “German-Russian Treaty.” It is also worth mentioning Koppen’s article of October 17, in which he wrote that Prussia and Russia had always had a common interest in Polish politics. The partitions of Poland represented only the long-brewing collapse of the state, as Koppen wrote.

The war was, according to propaganda, only the final stage of the joint revision of the Treaty of Versailles by the then loyal countries (Germany, Russia and Italy). Such a turn of events was also not entirely logical: why did the Soviet Union suddenly become equal to tsarist Russia from one day to the next? Journalists could not give an answer to this, although many readers probably liked the references to history, traditions, and the revision of modern racist theories.

The final act of this contradictory period was accomplished by the Soviet Union with the invasion of Finland. As mentioned, there was relative helplessness at the press conference as to how it could be classified. German sympathies were entirely on the side of the Finns. Goebbels wrote: “We must let go of the reins a little. Finnish reports are allowed to be printed. Our people are absolutely professional in this conflict. The Russians are not very good at psychological work” [see Goebbels].

According to Goebbels, the pro-Finnish position originated in the First World War, when a Finnish battalion of Jägers fought on the side of Germany against Russia, and later German soldiers in the Finnish Civil War supported the supposedly “civilian” side, as Goebbels wrote (in fact, the White Finns, against the Communists), in the struggle for the so-called “independence” and against the Reds, and therefore indirectly against Bolshevik Russia.

Since Finland’s independence was not a direct result of the Treaty of Versailles, propagandists could not use a revisionist argument as they did against Poland. The argument about the “unraveling of nations” was also irrelevant here, since the Finns, like Belarusians and Ukrainians, could not be called a fraternal Russian people. The previously carefully constructed propaganda arguments in favor of the division of Eastern Europe collapsed, and the contradictions could not be washed away by vague ideological arguments and overcome by new ideological constructs.

Consequently, the propaganda failed to explain the Soviet attack on Finland from an ideological point of view, as it had done in previous events. Officially, Germany was on the side of the USSR in this conflict, and Facebook directly adopted the Soviet version of what was happening. According to it, the war began because of Finnish provocations and border violations. FB denied rumors about the supply of weapons to the Finns [see FB 11.12.1939].

However, as Goebbels announced, he “lowered the reins a little”, so the reports of the Finnish army were published on a par with the Soviet ones. The propagandists clearly did not care that they often contradicted each other. Thus, on December 13, the Soviet report stated that the army was advancing on all fronts, while the Finnish report said that the Russians had been thrown back.

The impact of the press on the public

Abroad

Völkischer Beobachter was considered the mouthpiece of the National Socialist government of Germany and of Hitler personally. It would seem that no one abroad will read this, since he only reproduced what politicians said. In fact, the FB was still interesting because it reproduced the National Socialist position on more issues than the politicians themselves, and so more generally, it conveyed an image of Germany and National Socialism that, intentionally or unintentionally, influenced the attitudes of interested foreign observers.

The National Socialists were well aware that this particular newspaper was being taken into account abroad, and therefore after 1933 they tried to encourage the editorial board of this radical newspaper to adopt a more moderate position.

FB Exposure in the Soviet Union

The intense press campaign against Bolshevism, which lasted until April 1939, succeeded primarily in destroying relations with the Soviet Union and aroused fear, perhaps hope, that Germany would launch an anti-Bolshevik crusade.

Specific events, such as the German-Polish Pact of 1934, the Spanish Civil War, the Anti-Comintern Pact, the annexation of Austria, and the Munich Agreement, intensified the sense of threat in the Soviet Union and gave further impetus to the collective security policy promoted by the Soviet Union.

For the U.S.S.R., the danger of fascist aggression became more and more real, not only because of intelligence reports, but also because of the general poisoning of the atmosphere by Hitler and other leading National Socialists with their anti-Bolshevik pamphlets and speeches. German newspapers also contributed [see Weber and Haslam].

From May 1939, the Soviet Embassy in Germany recorded a more restrained rhetoric in German newspapers. The Soviet attorney for trade attaché in Germany, Georgy Astakhov, noted this in some reports, stressing that it could also be a tactical maneuver that could be reversed at any time.

In general, great importance was attached to the press in the negotiations. Diplomats on both sides interpreted the moderation of the controversy from May 1939 onwards as a sign of cooperation. At least the press also contributed to the emergence of the German-Soviet pact.

Exposure to FB in the UK

Another country for which the anti-Bolshevik controversy was broadcast was Great Britain. Hitler wanted to act in concert with Great Britain, or at least to obtain the tacit consent of the British to Germany’s eastward expansion [see Kershau]. He hoped to achieve this by means of propaganda [see Graml].

But German propaganda was unable to change British public opinion, in particular because of its own anti-British campaigns, which swept away the previously existing sympathies. So Hitler’s hopes that propaganda would influence British opinion were only an illusion. The anti-Bolshevik sentiment in Great Britain and the supporters of an alliance with Germany came more from some long-standing anti-Communist circles in England than from German propaganda.

An unintended side effect of the propaganda, however, was that key British politicians, like most observers, considered a rapprochement between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939 to be highly unlikely, and therefore, given the predicament in which the Soviet Union found itself, did not consider it necessary to make major concessions in the Anglo-Soviet negotiations of 1939. which formed the foundation for the British policy of appeasement.

And although the government in London noticed the containment of the anti-Soviet rhetoric of the German press since May, like the information received from the secret services about the German-Soviet rapprochement, this did not make them hurry or show more accommodating negotiations with the Soviet Union [PA, Nr. 338, ZSg. 102/4/89/36].

Impact of FB in other countries

Propaganda contributed to the fact that not only the British policy of appeasement, but also the foreign policy of a number of other countries, proceeded from the assumption of National Socialist-Soviet intransigence. This applies in particular to the inhabitants of the western fringes of the Soviet Union and the eastern periphery of Germany, who were particularly shocked by the German-Soviet pact and in some cases felt acutely threatened [see Kerschau, Longerich, Gordon].

For Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Finland and the Baltic states, the non-aggression pact represented a new political constellation that was difficult to imagine, since Germany and the Soviet Union were considered “ideological mortal enemies.” The foreign policy of many countries was based on the assumption that Germany and the USSR were incompatible, which led to corresponding decisions that seemed too “carefree and superficial” if this factor was not taken into account. For example, this had a strong impact on the collective security policy promoted by the USSR.

On the whole, the radical shift from anti-Bolshevik to pro-Soviet propaganda contributed to the fact that the official statements of the National Socialists aroused less and less confidence in the Allied states. Most likely, this greatly influenced the desire of Germany’s allies, such as Japan, to later support Germany in the war against the USSR. Hitler showed the world that he could act against the mood within his party in such a way that even such an influential hater of the Bolsheviks, and by then the publisher of FB, Alfred Rosenberg, could not resist him.

Another consequence of the pact was likely to underestimate Hitler’s aims vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. Therefore, many did not expect such an early attack on the USSR. On the other hand, no one outside Germany doubted Hitler’s unscrupulousness.

Impact on readers in Germany.

Preliminary remarks

When analysing the impact of FB reporting on readers in Germany, the question arises to what extent FB can be considered representative of all German newspapers or all German media (radio, newsreels, poster propaganda, etc.). This question is difficult to answer because a superficial examination of other German newspapers reveals quite significant differences in the reports on the Soviet Union in 1939. Further research by the German press is needed to find out for sure.

But in the future, we can still assume some common features:

- From January 1 to April 1939, all German newspapers, as well as the radio, probably followed the instructions for the press and from time to time in one way or another polemicized against the Soviet Union. FB was certainly one of the most radical German newspapers on the subject and played the role of a leader in the ideological indoctrination of Germans with anti-Bolshevik views.

- The transition from May to August from anti-Bolshevik to pro-Soviet propaganda was nowhere smooth. Here, too, it would be worthwhile to conduct a more detailed study.

- Probably, more than one journalist on the new wave rolled out the old national-Bolshevik ideas anew. Goebbels and Rosenberg, who hated each other, agreed that the commentaries on the pact often went too far.

Rosenberg himself was unequivocally opposed to the pact. On August 22, he wrote in his diary:

“On the instructions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the press has simply lost all dignity. The newspapers behave as if our struggle with Moscow was a misunderstanding and the Bolsheviks were the real Russians with all the Soviet Jews at the top! These hugs [with Russians] are more than shameful.”

Rosenberg blamed the pact on Ribbentrop, whom he called an anecdote of world history that had too much influence on Hitler.

Goebbels himself tried to put the brakes on the press only on September 24, but he did not succeed in this matter, most likely because of the too great influence of the Foreign Office, which received by order of the Fuehrer [ADAP, D, VIII, Nr. 31] of September 8, 1939, expanded competences. This also gave Goebbels reason to resent Ribbentrop.

Anti-Bolshevism was used by the German government to achieve goals such as strengthening a sense of unity and national society, domestic political mobilization for the regime, and to make Germans believe that a brutal Jewish clique ruled the Soviet Union and the Russian people, and that the Soviet Union was a threat against which war must be prepared. The Germans had to adopt “anti-Bolshevism” into their worldview or, if they already held it, to feel true to their position.

In what follows, it will be examined whether the National Socialists achieved their goal of creating a people’s community by means of an anti-Bolshevik image of the enemy. Had the Germans become staunch anti-Bolsheviks by 1939? Only in this case could it be assumed that anti-Bolshevism could be successful as a means of mobilization for war.

Has the goal of preparing for war been achieved?

The use of anti-communist hysteria was one of the regime’s most popular actions. Historian Ian Kershaw argues that the horrific brutality of the war of annihilation in the East was a consequence of the ideological hatred of “Jewish Bolshevism” that had been instilled in Germans for years under the Nazi regime. Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski asserted something similar: “If one preaches for years, decades, that the Slavic race is an under-race, that the Jews are not human beings at all, then something like this simply had to happen.”

The historian Florin writes that anti-communism in Germany had its beginnings rather in the political right-wing sector, which was losing more and more voters to the German Communist Party. Politicians fanned anti-communist hysteria. In foreign policy, on the contrary, they often expressed sympathy for the USSR as a country, while at the same time being anti-Bolshevik. For example, Russian literature was highly valued, and FB even called Dostoevsky “Völkischer,” i.e., a “people’s” writer [see Layton].

Donal O’Sullivan writes that the fiercest opponents of Bolshevism and the Soviet social system in Germany were the Social Democrats and the Catholic Church. No other party in Germany has so vehemently renounced communism as the Social Democrats.

In addition to the anti-communist sentiments fanned by the Social Democrats, they added Russophobia. The Catholic Church helped fan the flames of the anti-Communist fire, although it avoided Russophobia. Even the Bolsheviks had their sympathizers in the right-wing public, the National Bolsheviks [see O’Sullivan].

From 1933 onwards the polemics against the USSR were conducted more or less moderately, stronger in some publications, weaker in others. But the National Socialists were constantly having to reissue press instructions on the Soviet Union, as individual publications repeatedly published articles that described the USSR too positively. In the instructions of 1937 they even threatened to charge those who would violate these instructions with the accusation of betrayal of the Motherland [see Pietroff-Ennker]. From February to August 1937, eight instructions were issued to the press, demanding the continuation of propaganda against the Jews and the USSR. Obviously, these demands had to be repeated because of the reluctance of some journalists to follow such instructions [PA, Nr. 338, ZSg. 102/4/89/36 (3), 8.2.1937; PA, Nr. ZSg 102/9/117/Nr.221]. Although anti-Soviet propaganda was conducted, it was not carried out by all newspapermen.

It is safe to say that the German press did not achieve complete unity in its propaganda against the Soviet Union and the Jews until the end of 1937 and lasted until May 1939. From May 1939 to June 1941, Germany was considered an ally of the USSR, and did not conduct propaganda against it. It turns out that the ideas of anti-Bolshevism were not so long and not so intensively inculcated in the Germans as various researchers, such as Kershau, have hitherto assumed. The anti-Semitic ideology that has always permeated Facebook publications could shift either in the direction of the capitalist countries or in the direction of the USSR, depending on the requirements of the political situation.

However, Bach-Celewski claims to have heard sermons for decades about the Slavic race being a “sub-race.” Cielewski may have been referring to the publications and speeches of Alfred Rosenberg and Adolf Hitler, which he supposedly read and listened to as a National Socialist. However, in the radical racist FB, the claim that the Slavic race was a “sub-race” could not be found in 1939.

Even at the height of anti-Bolshevik propaganda in early 1939, Russians on Facebook were portrayed as victims of their Jewish oppressors who were to be pitied, not as “subhumans.” Here, as the example of Poland already in 1939 shows, the war led to the radicalization of propaganda, which slandered all opponents as representatives of the “sub-race”. Allies such as Romanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians and, until 1941, Russians were not to be subjected to racial humiliation.

After the German attack on the USSR, of course, everything changed dramatically, and the Russians also fell into the ranks of the non-commissioned officers, who had no right to live. The war had made propaganda much more influential on the minds of soldiers, as the killers now had a personal motivation to believe it. After all, it was easier to kill someone as “subhuman,” especially if they were civilians, women, or children. This served as an excuse for the crimes. Only then did propaganda become fully effective and strengthen the power of the racist-anti-Semitic government.

Despite instructions to curb the praises of the pact, the newspapers were full of rave reviews. Theodor Seibert was the most enthusiastic when he described the struggle of “totalitarian” states against “democracies.” Only Facebook published publications in which the protest was indirectly read.

The gap was felt not only in the editorial office of the FB, but also in the party. The anti-Bolshevik faction was at the disadvantage against the National Bolshevik faction, although it had an overwhelming majority. Rosenberg sent a memorandum to Hitler on October 2 demanding the post of “Fuehrer’s Representative for the Defense of the National Socialist Worldview.” In so doing, he apparently tried to counteract the growing pro-Bolshevik sentiments [see Pieper, Rosenberg].

In fact, this act shows us his powerlessness in the situation at the time. The pro-Soviet sentiments that Rosenberg hated even found their way into the last bastion of National Socialism, the FB newspaper.

The reaction of the German people to the pact concluded with the USSR also shows the ineffectiveness of the propaganda of anti-Bolshevism that had been carried on before. One of the clearest signs of discontent was the throwing of swastika armbands by some of Hitler’s followers on the night of August 25, 1939. These armbands were thrown over the fence of the Brown House in Munich, the headquarters of the NSDAP party from 1930 to 1945. But in other places, there was no such reaction. The historian Fleischhauer writes that Hitler’s fears of the party’s reaction to rapprochement with the Soviet Union were not confirmed. Fears that caused Hitler to delay this rapprochement as much as he could.

But the reactions in the population cannot be described as entirely positive. They were rather diverse. Discontent among the population was also noticeable. But it is worth noting that only the newspaper of the Social Democrats noted these negative reactions among the population [see SoPaDe, Nr. 6, 1939, S. 975]. Moreover, these reports were full of contradictions. Thus it was written that the old fighters of the party showed a negative reaction to the pact. But even this newspaper could not deny that many societies had shown mostly positive reactions. The newspaper also wrote that there had been a great disorder in the National Socialist community because of the conclusion of the pact, and immediately went on to say that there was no shortage of party members who would follow Hitler through everything.

This is not surprising, for it was the Social Democrats who traditionally had the most anti-Bolshevik sentiments and deliberately exaggerated the discontent of the German population. Most of all, they feared the Bolshevization of Germany. This fear stemmed from the danger of losing capital to the tycoons of the industry. Oddly enough, other tycoons, on the contrary, saw new opportunities for trade in alliance with the USSR. And even after the conclusion of the pact, no one doubted Hitler’s anti-communist sentiment.

Of course, there were also segments of the population who felt betrayed by the government. But soon everyone was joking about the pact. For example, at press conferences, people joked that Georgstrasse (Georg Street) in Berlin would soon be renamed Georgierstrasse (Georgian Street).

Journalist Fritz Sanger wrote that the people were now glad that war had been avoided. Winking, they whispered that “it was the world’s enemy number 1”, and as a continuation they added that they actually did not mind going to the Black Sea. Thus, we see that the German population associated the Soviet Union with something more than a simple image of the Bolshevik enemy. The overwhelming reaction of the people to the pact was simple joy at the end of the “Encirclement” and the avoidance of war.

An opponent of the regime, Ulrich von Hassel, wrote that most of the people he met saw the pact as a tactical masterstroke by the two dictators and welcomed the restoration of the historical link with Russia. Even Alfred Rosenberg, who regarded the pact as a kind of personal insult, had to admit that the people as a whole were relieved by the end of Encirclement. The Jewish philologist Victor Klemperer, the American correspondent in Germany William Shirer, and the Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wrote that most people welcomed the pact. The ambassador in Moscow, who had become very popular overnight, was showered with telegrams of congratulations from Germany, which he received with mixed feelings, contemplating the impending attack on Poland.

The SS-SD Security Service also reported that there was admiration rather than rejection among the people. In the meantime, there was also a case of discontent in the city of Oberhoufhausen. Chaplain Moder, in his sermon, said that the danger of Bolshevism had only increased because of Hitler’s fraternization with Stalin.

Rejection of the pact was found among those who felt slandered and betrayed, as the Social Democratic newspaper wrote. Only a few simply did not accept any interaction with the USSR. For example, Wehrmacht officer Helmut Groskurth wrote in his diary that the Soviet Union, in his opinion, had deceived the German government.

But soon the people had other concerns, such as the attack on Poland. Few people in Germany wanted another war, so the war was very poorly received, according to historians Ali, Shearer, and Kershau. However, the quick victory over Poland eventually added to Hitler’s popularity.

Trust Used

Long before the pact was signed, there were rumors that Hitler wanted to divide Poland from Russia. Victor Klemperer wrote in his diary on June 7, 1939:

“It is usually said that he will divide Poland between himself and Russia. And how little he cares about exposing his own lies: now they wrote that we never supported Spain (Franco), and now entire pages of newspapers glorify the Spanish Condor Legion with its cannons and planes. And every day there are speeches and parades or military exercises to prove our invincibility and our “peaceful will” […] But people do believe in peace. He wants to seize (or divide) Poland, the democracies will not dare to interfere.”

As you can see, the people did not have much confidence in the Fuehrer’s loyalty to his own principles. Propaganda was perceived by the people rather as a tool to deceive the enemy, and therefore did not reject it. False reports have been repeatedly revealed in articles about the USSR. In the instructions for the press, they tried to reduce their number by warning about the danger of losing the trust of readers. The blame for the false reports was laid on the Jews, who were plotting to undermine the confidence of the people in the German press. In one way or another, all this served to ensure that the people of Germany did not have much confidence in anti-Bolshevik propaganda during the previous years. Consequently, reactions to the alliance with the USSR were mostly positive.

As an example of the inconsistency of the information published on Facebook, we can cite the statements that in the USSR everything was controlled by Jews. Instructions were issued to the press instructing all well-known politicians to add their Jewish surnames. For example, Litvinov was always called Litvinov-Finkelstein. But after the purges that took place in the USSR in the 1930s, FB was unable to explain where these very Jews, who, according to him, ran everything, had gone. How did Stalin the Georgian remove Trotsky the Jew, Kamenev and Zinoviev?

In the German Reich people understood that they had been deceived somewhere, either in anti-Bolshevik propaganda before or now, when the pact was concluded. Researcher David Banchier writes that this was the reason for the loss of interest in politics. There was a gap between the sense of reality and the picture of the world painted by the press. But this did not lead to a loss of popularity of the regime among the people. Still, the advantages that the NSDAP party led by Adolf Hitler brought with it were too great. For example, the salaries of German soldiers were the highest among all armies in the world. At the same time, relatives of soldiers received payments at home, according to historian Ali Götz. In the conquered regions, the German mark was artificially appreciated, so that soldiers could buy and send home a lot of goods; And these are just a few examples. In general, the regime knew how to win the sympathy of the people.

Coming to Your Senses After Confusion

If we take the personality of Admiral Kurt Fricke in 1940 as representative of the German military, we can distinguish that he clearly had problems with separating purely propaganda clichés from reality. He did not want to believe unconditionally that the Soviet population would rise up against their government in the event of a German attack on the USSR, as FB assured before the German-Soviet rapprochement. The only thing he was sure of was that most people in the USSR were unhappy.

On the whole, however, he, like almost all military personnel, believed that the Soviet Union was militarily weak, largely due to the “great purges,” internally torn apart, and quickly defeated. Fricke noted that the reports on Russia were constantly contradictory. His notes show how little trust he had in German propaganda.

The FB newspaper, with its contradictory reports on Russia, which sometimes had an obvious ideological bias, sometimes tried to explain the emergence of the pact, did not bring any light to the idea of the USSR. Most likely, thanks to such reports, most German military and politicians were preparing for war with the USSR, relying on the stereotype of a “colossus with feet of clay”, which only needed to be swayed a little for it to crumble on its own. The degree of internal consolidation of Soviet power with the people was completely underestimated.

Due to the inconsistency of the propaganda, no one ended up knowing what information about the Soviet Union was reliable and what was being disseminated for various propaganda reasons. This bewildering information policy, which opened the floodgates for the revival of stereotypes, had a fatal effect on the ensuing war far more than anti-Bolshevik indoctrination.

Results

In general, we can come to several important conclusions. German propaganda was not the miracle portrayed by some scholars, such as Hagemann. It had quite pragmatic reasons and was conducted in accordance with the current political situation.

Anti-Bolshevism in propaganda was used mainly to show the world the evil intentions of the Jews, who allegedly plotted and ruled the world. At the same time, the USSR was a very convenient target, since no one could double-check all the fictions about this country, since it was far away.

Fanatics like Alfred Rosenberg in the Party were free to vent all their hatred, and Hitler used it for his own ends. “Prosperous” National Socialist Germany was contrasted with the “Jewish-ruled USSR,” in which “poverty and devastation reigned.” From a foreign policy point of view, Hitler tried to use the “anti-Bolshevik banner” to gain new allies.

After the change of course, the insufficiency of the “anti-Bolshevik indoctrination” of the population was exposed. The effectiveness of propaganda turned out to be negligible. It was too difficult for the people to believe that Bolshevism was to blame for all the ills of the world, and that in the USSR there was nothing but oppression and poverty. Especially journalists like Theodor Seibert, who had already personally visited the USSR, knew that this was not the case. Readers did not become infected with virulent anti-Bolshevism, as Alfred Rosenberg, who had a personal score to settle with the Bolsheviks, would have liked.

Most people expressed joy that the war had been avoided. The fact that the pact was made with a sworn enemy, the Soviet Union and the “destroyer of culture” of all people, amused rather than provoked protests and anxiety. Of course, relief was also caused by the fact that the Soviet Union was perceived as a threat, presumably because of the threat of a war on two fronts, which no one, not even Hitler, wanted.

The claim that the National Socialist image of Russia, with its incomparably negative and aggressive features, was the ideological engine of the war of annihilation, seems to be insufficiently thought out and proven. The very fact that the Germans, two years before the start of the war against the Soviet Union, were not imbued with anti-Bolshevik ideology, but were already waging wars, creating ghettos and concentration camps, should give food for thought. Therefore, it seems important to distinguish between pre-war and war propaganda.

Author – Vasily Zaitsev