Socially dangerous children

Author: Tatyana Polyanskaya, PhD in History, Senior Researcher at the State Museum of the History of the Gulag

From the collection of the State Museum of the History of the Gulag.

The Great Terror. In 1937, unprecedented, unprecedented repressions affected all strata of the population: from the leaders of the party and the government to ordinary citizens. Members of the C.P.S.U.(B.) and illiterate peasants who could not even repeat the wording of their accusation could be accused of counter-revolutionary activity, of organizing terrorist acts, of espionage and sabotage. The mass media demonstrated unprecedented enthusiasm for exposing “enemies of the people,” and yesterday’s leaders and heroes were turned into “despicable spies and traitors to the Motherland.”

“Enemies of the people” had families, “criminal” fathers and mothers had children. Everyone is well aware of the slogan “Thank you to Comrade Stalin for our happy childhood!” that appeared in 1936, it quickly came into use, sounded from posters and postcards depicting happy children under the reliable “protection” of the Soviet state. But the authorities decided that not all children deserve a cloudless and happy childhood. At the height of the Great Terror, on August 15, 1937, the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR, N. I. Yezhov, signed the operational order of the NKVD of the USSR No. 00486 “On the operation to repress the wives and children of traitors to the Motherland.” According to the document, the wives of those convicted of “counter-revolutionary crimes” were to be arrested and imprisoned in camps for 5-8 years, and their children aged 1-1.5 to 15 were sent to orphanages. In each city where the operation to repress the wives of “traitors to the Motherland” took place, children’s reception centers were created, where the children of the arrested were admitted. The stay in the orphanage could last from a few days to months. Lyudmila Fyodorovna Petrova from Leningrad, the daughter of repressed parents, recalls: “They put me in a car, my mother was dropped off at the Kresty prison, and we were taken to a children’s reception center. I was twelve years old, my brother was eight. First of all, they shaved our heads, hung a plaque with a number around our necks, and took fingerprints. My brother cried a lot, but we were separated, we were not allowed to meet and talk. Three months later, we were brought from the children’s reception center to the city of Minsk.”

Artist N. Vatolina. “Thank you dear Stalin for a happy childhood!” 1939

From orphanages, children were sent to orphanages. Brothers and sisters had little chance of staying together, they were separated and sent to different institutions. From the memoirs of Anna Oskarovna Ramenskaya, whose parents were arrested in 1937 in Khabarovsk: “I was placed in a children’s reception center in Khabarovsk. I will remember the day of our departure for the rest of my life. The children were divided into groups. The little brother and sister, having found themselves in different places, cried desperately, clinging to each other. And they asked them not to separate all the children. But neither the pleas nor the bitter crying helped… They put us in freight cars and drove away…”

A huge number of orphaned children were sent to already overcrowded orphanages. Thus, as of August 4, 1938, 17,355 children had been removed from their repressed parents, and another 5,000 children were to be removed. In total, during the operation, 18,000 wives of those arrested were imprisoned and camped, and more than 25,000 children were placed in orphanages.

Nelya Nikolaevna Simonova recalls: “In our orphanage lived children from infancy to school. We were poorly fed. We had to climb through garbage dumps, feed on berries in the forest. A lot of children got sick and died. We were beaten, forced to stand on our knees in the corner for a long time for the slightest prank… Once, during a quiet hour, I couldn’t sleep. Aunt Dina, the teacher, sat on my head, and if I hadn’t turned around, I might not have been alive.”

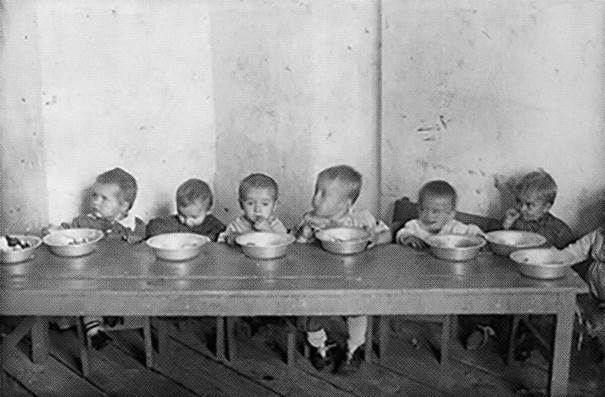

Photo from the photo album “Children’s Home of the Kargopol Corrective Labor Camp”. 1945. From the funds of the Civil Aviation of the Russian Federation

Physical punishment was widely used in children’s homes. Natalia Leonidovna Savelyeva from Volgograd recalls her stay in the orphanage: “The method of upbringing in the orphanage was on the fists. In front of my eyes, the director beat the boys, heading their heads against the wall and punching them in the face, because during a search she found bread crumbs in their pockets, suspecting them of preparing bread for escape. The teachers told us: “Nobody needs you.” When we were taken out for a walk, the children of the nannies and teachers pointed their fingers at us and shouted: “Enemies, enemies, enemies!” Our heads were shaved bald, and we were dressed casually.”

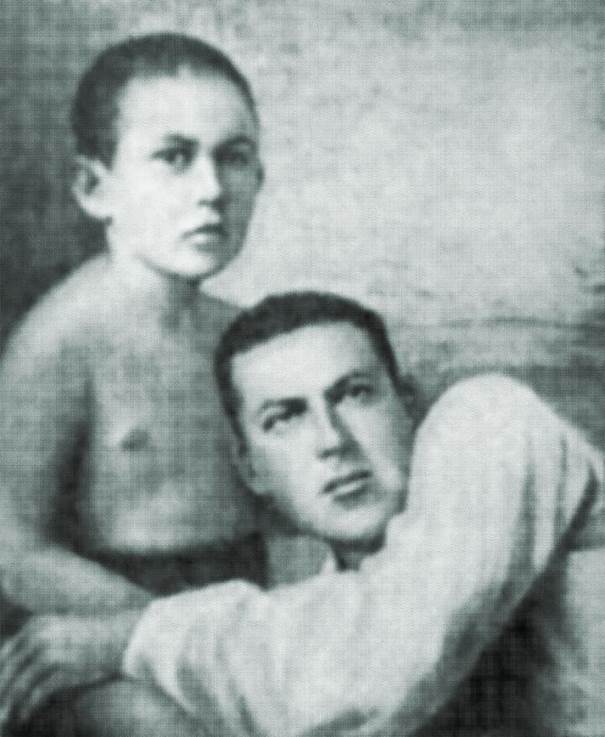

Children of repressed parents were considered as potential “enemies of the people”, they fell under severe psychological pressure from both employees of children’s institutions and peers. In such an environment, the child’s psyche suffered first of all, it was extremely difficult for the children to preserve their inner spiritual peace, to remain sincere and honest. Mira Uborevich, the daughter of Commander I. P. Uborevich, who was shot in the Tukhachevsky case, recalled: “We were irritated and embittered. They felt like criminals, everyone started smoking and could no longer imagine ordinary life and school for themselves.” Here Mira writes about herself and her friends – the children of Red Army commanders shot in 1937: Svetlana Tukhachevskaya (15 years old), Pyotr Yakir (14 years old), Victoria Gamarnik (12 years old) and Giza Steinbrück (15 years old). Mira herself was 13 years old in 1937. The fame of their fathers played a fatal role in the fate of these children: in the 1940s, all of them, as adults, were convicted under Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (counter-revolutionary crimes) and served their sentences in corrective labor camps.

The Great Terror gave rise to a new category of criminals: in one of the paragraphs of the NKVD order “On the operation to repress the wives and children of traitors to the Motherland”, the term “socially dangerous children” appears for the first time:

“Socially dangerous children of convicts, depending on their age, degree of danger and possibility of correction, are subject to imprisonment in camps or corrective labor colonies of the NKVD or placement in children’s homes of the special regime of the People’s Commissariat of the Republics.”

At the dacha of the Commander of the 1st rank I. P. Uborevich. From right to left: Mira Uborevich, Svetlana Tukhachevskaya, far left – Nadya Uborevich.

The age of children falling into this category is not specified, which means that such an “enemy of the people” could be a three-year-old child. But more often than not, teenagers became “socially dangerous.” Pyotr Yakir, the son of Commander I. E. Yakir, who was shot in 1937, was recognized as such a teenager. 14-year-old Pyotr was deported with his mother to Astrakhan. After his mother’s arrest, Pyotr was accused of creating a non-existent “anarchist horse gang” and sentenced to 5 years in prison as a “socially dangerous element.” The teenager was sent to a children’s labor colony. About his repressed childhood, Yakir wrote his memoirs “Childhood in Prison”, where he describes in detail the fate of teenagers like him.

In the course of time, the situation of children of repressed parents in orphanages required greater regulation. Order No. 00309 of the NKVD of the USSR “On the Elimination of Abnormalities in the Maintenance of Children of Repressed Parents” and Circular of the NKVD of the USSR No. 106 “On the Procedure for the Placement of Children of Repressed Parents Over the Age of 15″ were signed on May 20, 1938. terrorist sentiments and actions.” If children who reached the age of 15 showed “anti-Soviet sentiments and actions,” they were put on trial and sent to corrective labor camps on special orders of the NKVD.

Minors who ended up in the Gulag constituted a special group of prisoners. Before being sent to a forced labor camp, the “juveniles” went through the same circles of hell as adult prisoners. Arrest and transfer followed the same rules, except that the juveniles were kept in separate wagons (if any) and could not be shot at. Juvenile prison cells were just as vile as adult cells. Often children found themselves in the same cell with adult criminals, then there was no limit to torture and humiliation. Such children came to the camp completely broken, having lost faith in justice. The “youngsters”, angry at the whole world for taking away their childhood, took revenge on the “adults” for this. L.E. Razgon, a former Gulag prisoner, recalls that the “minors” were “terrible in their vengeful cruelty, unbridled and irresponsible.” Moreover, “they were not afraid of anyone or anything.” We have practically no memories of teenagers who went through the Gulag camps. Meanwhile, there were tens of thousands of such children, but most of them were never able to return to normal life and joined the criminal world.

Soviet military commander I. E. Yakir with his son Peter. 1930. Photo from the book: A. M. Larin-Bukharin. An unforgettable. Moscow, 2002

Many women who went through forced labor camps and managed to survive in inhumane conditions for the sake of their orphaned children received news of the death of a child in an orphanage. For example, Gulag prisoner M. K. Sandratskaya learned about the death of her daughter Svetlana:

“Svetlana fell ill mentally in an orphanage. My daughter is dead… When I asked about the cause of death from the hospital, the doctor replied: “Your daughter was seriously and seriously ill. The functions of brain and nervous activity were impaired. Separation from her parents was extremely difficult. She didn’t eat. I left it for you. She kept asking: “Where is your mother, was there a letter from her? Where’s Daddy?” She only called plaintively: ‘Mother, mother…'”

Photo from the photo album “Yagrinsky Corrective Labor Camp”. 1946. From the funds of the Civil Aviation of the Russian Federation

The law allowed children to be placed in the custody of relatives who had not been repressed. According to the circular of the NKVD of the USSR No. 4 of January 7, 1938 “On the procedure for issuing for guardianship to relatives of children whose parents were repressed,” future guardians were checked by the regional and regional departments of the NKVD for the presence of “compromising data.” But even after making sure of their reliability, the NKVD officers established surveillance of the guardians, the moods of the children, their behavior and acquaintances. The children whose relatives in the first days of arrest, having gone through bureaucratic procedures, registered custody, were lucky. It was much more difficult to find and pick up a child who had already been sent to an orphanage. It was not uncommon for a child’s surname to be incorrectly recorded or simply changed. M.I. Nikolaev, the son of repressed parents, who grew up in an orphanage, writes: “The practice was as follows: in order to exclude any possibility of reminiscences, the child was given another surname. Most likely, the name was kept, the child, although small, was already used to the name, and the surname was given a different one… The main goal of the authorities, who took away the children of the arrested, was to ensure that they did not know anything about their parents and did not think about them. So that, God forbid, they do not grow up to be potential opponents of the authorities, avengers for the death of their parents.”

Photo from the photo album “Children’s Home of the Kargopol Corrective Labor Camp”. 1945. From the funds of the Civil Aviation of the Russian Federation

According to the law, a convicted mother of a child under the age of 1.5 could leave the baby with relatives or take her with her to prison and camp. If there were no close relatives willing to take care of the baby, women often took the baby with them. In many labor camps, Children’s Homes were opened for children born in the camp or who came with their convicted mother. The survival of such children depended on many factors, both objective: the geographical location of the camp, its remoteness from the place of residence and, consequently, the duration of the stage, on the climate; and subjective: the attitude of the camp staff, educators and nurses of the Children’s Home to the children. The latter factor often played a major role in the child’s life. Poor care of children by the staff of the Children’s Home led to frequent outbreaks of epidemics and a high mortality rate, which varied from 10% to 50% in different years.

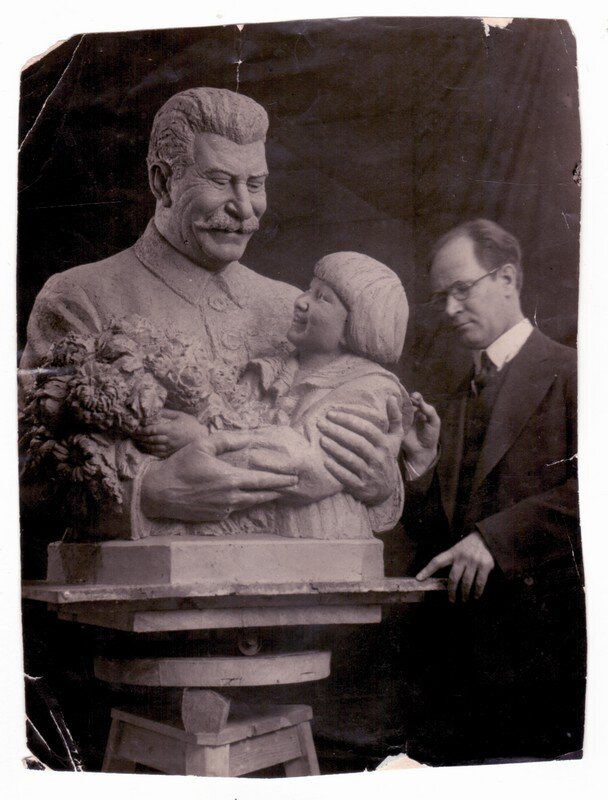

Sculptor T. Lavrov at his work “Thanks to Comrade Stalin for Our Happy Childhood”. 1936

From the memoirs of former prisoner Hava Volovich: “A group of seventeen children relied on one nanny. She had to clean the ward, dress and wash the children, feed them, heat the stoves, go to all sorts of subbotniks in the prison and, most importantly, keep the ward clean. Trying to make her work easier and find herself some free time, such a nanny invented all sorts of things… For example, feeding… From the kitchen, the nurse brought a hot porridge. Placing it in bowls, she snatched the first child she came across from the crib, bent his arms back, tied them with a towel to his body, and began to stuff hot porridge like a turkey, spoon by spoon, leaving him no time to swallow.

When a child who survived the camp was 4 years old, he was given to relatives or sent to an orphanage, where he also had to fight for the right to live.