“Set your sights on the West!”

Russia, and later Russia, has always been a European country. The culture, language, traditions and way of life of the East Slavic tribes, and later of the Russian people, are an integral part of the common European civilization. An indicator of belonging to Europe was Christianity, which unified the cultural and legal space of Europe. In Europe, no one doubted that Russia was a European country. Of course, Rus (Russia) was a peculiar part of Europe. But its differences from other European countries were no greater than those between Sweden and Portugal, or between the Czech Republic and Ireland. All non-European civilizations – Islamic, Chinese, Indian, Japanese – were alien, although close contacts with the nearby Islamic civilization left a deep imprint on Russia (Russia).

Nevertheless, for centuries there has been an ongoing debate about whether Russia is a European country or a separate civilization. Ideological constructs preaching the civilizational independence of Russia were born in the 16th century, and in various versions continue to exist to this day, from time to time becoming dominant in the public consciousness. One of the periods of such dominance was the Soviet era: during its existence, Soviet power evolved from the position “we are the best Europeans” to the declaration of the USSR as a separate civilization.

The Bolshevik Party was formally Western: Marxism, which it raised as a banner, was a European ideology. The top of the RCP(B) consisted of Westernizer Germanophiles: in the opinion of Lenin, Trotsky and their entourage, the socialist revolution would be successful only if it spread to the developed European countries. And above all, to industrial Germany. From their point of view, Russia, as “the most backward of the imperialist countries,” was to play the role of the fuse, the military and resource base of the world revolution, which they conceived as primarily European. The fate of Russia and its peoples was of little interest to the Bolshevik elite – it is enough to read Lenin’s statements about the Russian people to be convinced that the “leader of the revolution” did not respect or appreciate him. The same can be said about his associates. The Red Army’s campaigns in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland in 1919-20 were caused not so much by the desire to restore the territory of the former Russian Empire as by the desire to break through to the center of Europe and establish Soviet power there (primarily in Germany). The Bolsheviks made no secret of it.

Fighters of the Workers’ Revolution!

Set your sights on the West.

In the West, the fate of the world revolution is being decided.

Through the corpse of White Poland lies the path to world conflagration.

On bayonets we will carry happiness

and peace to working humanity.

To the West!

To decisive battles, to thunderous victories!

(Pravda, May 9, 1920)

The Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) spent huge sums of money to help like-minded Europeans, taking them away from the distressed people. Left-wing socialists frequented Red Moscow and, with the help of the Soviet government, with funds received from the USSR, they created a network of communist parties around the world. But the main efforts and funds were spent by the Bolshevik leadership on the European Communist Parties, and on attempts at communist coups in European countries. The short-lived “Soviet” republics in Hungary, Bavaria, and Slovakia fueled the Bolsheviks’ hopes for an imminent European revolution; and there were also “Soviet” republics even in the French Alsace and in the Irish city of Limerick.

The fact that the Bolshevik leadership was Westernized was convincingly explained by Dmitry Bykov in his essay “Gentlemen, all over again. Dmitry Bykov’s Manifesto” (Novaya Gazeta, June 2, 2017): “… The three main features of the Soviet project, directed precisely against Russian traditionalism, were: the cult of enlightenment; atheism (or at least the rejection of religion as a worldview basis); Internationalism and even, if you like, cosmopolitanism – that is, the relocation of nationalism to the closet of obsolete worldviews where it belongs. The Soviet Union turned out to be the last refuge of modernity, ruined in Europe by two world wars. This is the main paradox of the 20th century – the most backward country turned out to be the most advanced in the end…”

The Soviet avant-garde in art and constructivism in the architecture of the 1920s confirm the commitment of the early Soviet government to Art Nouveau, i.e. to the European foundations of art and culture. Thousands of left-wing enthusiasts came to Soviet Russia and then to the Soviet Union from all over the world, but mostly from Europe and America. At the same time, the USSR continued its undeclared war against Europe until the summer of 1920, despite the peace treaties. In 1920, the RSFSR concluded peace treaties with Estonia (February) and Latvia (August), and in March 1921 a peace treaty was signed with Poland. For Soviet Russia, these treaties were empty pieces of paper – Moscow had no intention of fulfilling them. In August 1921, immediately after the signing of the treaty with Latvia, Lenin wrote to the deputy chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, Sklyansky: “Under the guise of the ‘greens’ (we will later blame them) we will march 10-20 versts and hang the kulaks, priests, and landlords. Bonus: 100,000 rubles for the hanged man.” This means “passing” through the territories of Estonia and Latvia. And they “passed”, and repeatedly. On December 1, 1924, Soviet officers who had illegally arrived in Tallinn attempted an armed seizure of power, but were defeated by government troops.

In Poland, the sabotage units of the Red Army “partisans” until in February 1925, when the Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) decided to stop the senseless sabotage war, which did not receive support from the population.

In October 1923, Soviet agents raised an uprising in Hamburg, Germany, despite the fact that in 1922 the Treaty of Rapallo was concluded between Soviet Russia and Germany, which was extremely beneficial for the Soviets. In September 1923, Soviet agents leading the Communist Party of Bulgaria raised an uprising in that country, which ended in a terrible massacre.

All this was done for the sake of establishing Soviet power in these countries and incorporating them into the USSR. Soviet Europe was the goal of the Bolsheviks of those years.

The sympathy of European and American workers for the “Russian Revolution” gradually evaporated as information accumulated about what it really was. The devastation, the tyranny of the Bolsheviks, the terrible famine, from which the Soviet peasants were saved not by the “power of the workers and peasants” but by the American “imperialists”, the blatant immorality of the Bolshevik activists (and how could it be otherwise, if a significant part of them were criminals?) – all this was seen by the Western left, who visited the USSR, and described in articles and public speeches. The left-wing parties, which had been balancing between the Second Socialist International and the Third Communist International, the “second and a half” International, returned to the fold of social democracy.

But it’s not just the European left that has become disillusioned with the Bolsheviks – the Bolsheviks have also become disillusioned with the European left. “We expected uprisings and revolution from the Polish workers and peasants, but what we got was chauvinism and stupid hatred of the ‘Russians,'” Kliment Voroshilov lamented.

In December 1924, Stalin, who was gaining strength, in his article “On the Foundations of Leninism,” for the first time (Lenin’s individual statements on this subject are unimportant) allowed the building of socialism in a single country, i.e., in the USSR. This meant that the world revolution for the Bolsheviks was relegated to the background, and the consolidation of power at home came to the fore. This did not preclude any assistance to the “world revolution”: it continued until the fall of the Soviet system in 1991.

The Bolsheviks’ disillusionment with the European proletariat was a disillusionment with the West as a whole. Their interests were increasingly concentrated in the East: in May 1924, Soviet military specialists helped Chiang Kai-shek organize the Whampoa Military Academy in southern China. Subsequently, the Soviet military took an active part in civil wars and anti-Japanese resistance in China. At the same time, Moscow was almost not interested in “Western” Mexico, where in the 1920s and 1930s the leftist generals Obregón, Calles, and Cárdenas (they called themselves Bolsheviks, and the latter even called themselves Marxist-Leninists) were in power.

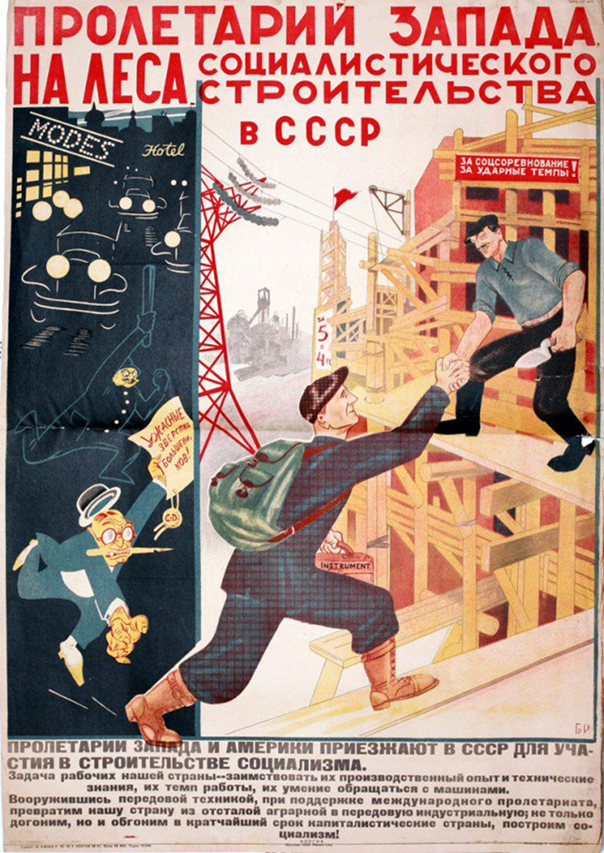

The apogee of the USSR’s rapprochement with Europe and the United States was the First Five-Year Plan. In 1927-28, when the Soviet leadership decided to move to accelerated industrialization, mass repressions against the Corps of Engineers began in the USSR. In 1928-30 thousands of “bourgeois specialists” were dismissed from their jobs; The Shakhty case, the Industrial Party case, the Labor Peasant Party case, and the trial of the Union Bureau of the Mensheviks mowed down domestic specialists, whose ranks had already been reduced by the civil war and emigration. The Soviet government did not trust domestic specialists, believing that foreign engineers were more loyal. It is not known how many foreigners came to the USSR for industrial construction (the documents were either classified or destroyed). The minimum figure found in the media is 70-80 thousand, of which 18 thousand are Americans; The maximum number of Americans alone is set at 200,000. The truth is obviously somewhere in between.

Foreigners, primarily Americans, laid the foundation of Soviet industry during the First Five-Year Plan and, to some extent, the Second Five-Year Plan. The 1,500 enterprises of the chemical, aviation, electrical, petroleum, mining, coal and metallurgical industries, factories for the production of automobiles, tractors and aircraft engines – in other words, everything that is considered to be the achievements of the first five-year plans was designed by foreign (mainly American) companies, built with the decisive participation of foreign engineers and skilled workers, and provided with foreign machinery and equipment. The main designer of the factories of the First Five-Year Plan was the design firm of Albert Kahn. Among those built by foreigners are Dneproges, Magnitogorsk, Uralmash, GAZ, AZLK, Stalingrad and Chelyabinsk Tractor Plants. German architect Ernst May designed 20 workers’ camps. American and European teachers trained 300,000 Soviet specialists at the workers’ faculties, laying the foundations of the Soviet technical intelligentsia.

For some time, the Soviet leadership and Stalin personally hoped for something like a Soviet-American convergence: the “great leader” spoke of combining “Russian revolutionary sweep” with American “efficiency.”

However, convergence did not work. Soviet workers did not like foreigners, who received much higher salaries and lived in incomparably better conditions. Foreigners were also envied by Soviet officials, who also tried to “christen” them into the communist faith and force them to give money to various foundations such as the International Organization for Assistance to the Fighters of the Revolution.

Foreigners, some of whom came to the USSR because they were fascinated by the ideas of socialist construction, were also dissatisfied with their situation. “Foreign employees of ChTZ, for example, wrote that… The apartments are insufficiently furnished, in the middle of the year their children were denied admission to school, salaries are delayed and paid in rubles. Medical care is at a low level. One worker was treated for a dislocation instead of a broken leg. As a result, specialists began to quit their jobs without completing their contracts. …

In short, the contract promised one thing, but in reality it turned out to be quite different. And foreign experts spoke frankly about this at meetings. For example, in February 1935, Mielke, a skilled worker and member of the Communist Party of Germany, said: “I, an old worker with a lot of experience in the Communist Party, if I go to Germany and speak at meetings there, will tell the whole truth about how badly the workers in Russia really live. The unemployed in Germany are a thousand times better off than here. Here the worker has no right at all, everything is dictated by one person, and the worker must dance to the tune of the oppressor” (“History from below: the life and fate of foreign workers and specialists in the USSR in the 1920s-1930s.

“Foreigners saw starving workers who only pretended to be engaged in production, but in fact were engaged in making lighters and keys to earn money for food. Many noted that they did not see such terrible living and working conditions as in the USSR in the capitalist system. French workers noted that even… the homeless in France dress better than most Soviet citizens” (Yegor Sennikov, “Out of the Fire and into the Flames: Stories of Western Immigrants in the USSR”).

As early as 1932, the number of foreigners leaving the USSR (including those who terminated their contracts ahead of schedule) greatly exceeded the number of those who entered. In the same year, foreigners began to write home about the terrible famine that struck the USSR, and in 1933, photographs from the famine-stricken areas appeared in Western newspapers, such as posters reading “Eating children is a crime!” The Western press was filled with articles and letters from engineers and workers who had returned from the USSR, in which the “first state of workers and peasants” was portrayed as a cross between hell and garbage.

The reaction of the Soviet leadership was corresponding. Attempts were made to deport foreigners after the completion of the most necessary work under contracts, they were forbidden to visit areas affected by famine, and the mail was intercepted. What remained were mainly convinced communists, political emigrants who could not return because of the danger of repression in their homeland, and economic refugees (mainly from Finland, Poland and Romania). These categories were mostly shot or sent to the Gulag in 1937-38.

The mutual discontent between foreigners who came to the USSR en masse in the early 1930s and the Soviet people had ideological consequences. The West began to be seen not only as a “capitalist reserve” but as something mockingly opposed to Russia, whether Soviet or Tsarist. The atmosphere of general suspicion and pathological espionage mania provoked the emergence of a specific phenomenon by the beginning of the Great Terror – Soviet nationalism. It flourished during the Great Patriotic War, in which the Red Army was opposed not only by German, but also by Hungarian, Croatian, Romanian and Italian troops, as well as SS volunteers from most European countries.

It was hard not to recall that Napoleon’s campaign against Russia was dubbed the “invasion of twelve languages” – i.e. the aggression of the “collective West”. Although similar notes were already sounded during the civil war – hence the lie about the “intervention of 14 powers”. The old ideology of the treacherous West, seeking to conquer and destroy Russia, turned out to be much more tenacious than the thousand-year-old monarchy. Released in 1938, at the height of the Great Terror, the feature film Alexander Nevsky presented viewers with a false version of historical events, in which German “dog-knights” tried to conquer Russia, like Hitler’s German Nazis.

After the end of the war, the Soviet version of the ideology of “Moscow is the Third Rome” was finally formed. Europe, saved from Hitlerism, according to Soviet ideology, by the Red Army, did not feel much gratitude to it, and even allowed itself to assert that the United States played a decisive role in the defeat of Nazism. Worse still, the countries of Eastern Europe, where the Red Army established the rule of local communists (most of whom came from Moscow and were Soviet citizens), sometimes refused to thank the Soviet Union for saving themselves, and resented the fact that Soviet military and civilian structures had settled in their countries as the victors.

After the war, Stalin and his entourage at some point believed that the democracies would allow them, the victors of Nazism, to do whatever they wanted. The USSR demanded the transfer of Turkish Armenia, the Bosporus, and the former Italian colonies (Libya, Somalia and Eritrea), but was refused. In Greece, the British troops did not allow the Communists to seize power in that country, and in China, the Americans, albeit sluggishly and ineffectively, tried to help Chiang Kai-shek’s army, which was resisting the offensive of Mao Zedong’s troops. In 1946, when the Soviet army, contrary to the 1941 agreements, tried to remain in Iran and even expand the zone of occupation (while British and American troops left the country), US President Truman openly threatened Moscow with the use of nuclear weapons. In 1949, the conflict between Stalin and Tito reached such a pitch that a Soviet invasion of Yugoslavia seemed inevitable. Under these conditions, the United States concluded a military assistance treaty with Tito, according to which Yugoslavia received American weapons.

Israel played a special role in the growth of Soviet distrust of the West. Stalin was confident that the Jews, most of whom were socialist and grateful to the Soviet army for saving them from the Nazis, would become staunch allies, and that Israel would become a kind of “people’s democracy” that could be ruled from the comfort of the Kremlin.

However, Israel, which had gone out of its way to show its respect to the Soviet Union, refused to become Stalin’s puppet. Moreover, during Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir’s visit to Moscow, the Soviet leadership was outraged to learn that Soviet Jews considered themselves Jews first and Soviet Jews second. This sparked an outburst of anti-Semitism at the highest levels, culminating in the “Doctors’ Affair” and preparations for the deportation of Jews to the Far East, which was thwarted by the death of the “great leader.”

In the early 1950s, the Soviet Union’s sense of a “besieged fortress” reached its climax. Almost all Europeans were now considered enemies (and the citizens of the “people’s democracies” were unreliable allies, something like “cunning slaves”). An exception was made for Asians: this was a time of special relations between the USSR and China and its vassals, North Korea and North Vietnam. The European world was declared an enemy: the Soviet media wrote that Western countries were ruled by fascists, about US plans to drop 100 atomic bombs on the USSR, about the deployment of saboteurs and terrorists by Western special services (which was partly true: before Stalin’s death, Western intelligence services helped anti-Soviet armed groups in the Baltic States and Ukraine, but Soviet intelligence also helped communist saboteurs, for example, in Greece).

Anti-Western hysteria reached the point that in 1947 Soviet citizens were forbidden to marry foreigners, and previous marriages were ordered to be dissolved.

From 1917 to 1950, Soviet power came full circle: from presenting Soviet Russia as an integral part of the West to completely opposing the USSR to the West as such – in politics, culture, and spiritual foundations. The “Third Rome” was once again reborn, trampled on ideological enemies, and appeared in a new guise – Bolshevik, Soviet.