With whose help did the German blockade lead to the collapse of the Russian economy?

At the end of 1920, when it became obvious to everyone that the Civil War was nearing its end, the fight against the crisis that paralyzed everything and everyone became a task of paramount importance for the leaders of Soviet Russia. In order to develop effective measures to overcome the devastation that began during the First World War, it was necessary to answer many serious questions, which in fact boiled down to one main thing: how could it happen that the economy of a country that had huge human and natural resources, had not the most powerful, but sufficiently developed industry, in a matter of months after the start of the war, fell into a completely degenerate state?

‘Complete dichotomy’ of power’

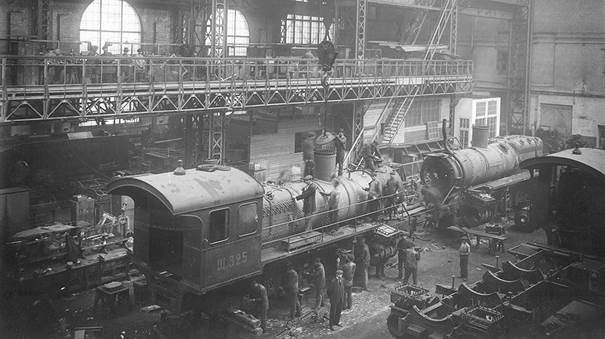

Photo: RGASPI/Rosinform “With the declaration of war, 43,000 new wagons and 1,500 steam locomotives were ordered to Russian factories for 1915”

The first alarming signs of impending economic catastrophe appeared shortly after the outbreak of the World War, in the autumn of 1914. And very soon, when the crisis began to spread and grow, the railways began to be blamed for all the country’s troubles. More precisely, a system of their management, created in wartime. For example, on September 4, 1917, the former chairman of the State Duma, M. V. Rodzianko, told at a meeting of the Extraordinary Investigative Commission created by the Provisional Government to investigate the illegal actions of former senior officials:

“It turned out, for example, that there was a train with some troops. Up to a certain demarcation line, it is under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Railways, and when he crosses this line, it falls under the control of an unknown person. There was a gene. Ronzhin, who was allegedly in charge of the communication routes. The train, having crossed some imaginary line on the map, was no longer under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Railways. This duality went on. Where does the devastation of communication routes come from? From this wrongly stated principle. There is always a source and chaos ensues. The staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief or his administration decided that all this should be put on a military footing. They recruited various captains, more or less incapable of military service, and made them commandants. As a result, there was a double boss at the railway stations. (I’m starting at the bottom because it’s gone to the top.) The commandant is vested with full power almost up to and including the shooting, and so is the station master, because the railways are recognized under martial law. He, too, is endowed with great power. And these two elements collide with each other. It got to the point (I was complained about on my trips to headquarters on the way) that on the one hand, where the stationmaster was more energetic, he would attack the commandant, and where the commandant was more energetic, he would almost threaten the stationmaster with a revolver: “I am the boss.” That’s how it started. On my very first trip to the headquarters, I spoke with the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich that this was impossible, it was chaos. It was in August or September, when I went for the first time: ‘This chaos began with the railways and gradually affected the whole departure of the units of the immediate rear, then it will go deeper, and you will get a complete split of power, otherwise anarchy.'”

But in reality, everything was not so straightforward and simple. In 1920, specialists from the People’s Commissariat of Railways (NKPS) compiled an extensive report, in which they collected and analyzed all the circumstances that led to the devastation. They believed that the main problem that started the crisis was the fuel difficulties resulting from Germany’s successes at the front and the German blockade:

“With the occupation of the Dombrovsky coal basin by Germany, Russia lost 390,000,000 poods of coal a year; And with the blockade of the ports of the Baltic and Black Seas, a further 500,000,000,000 imported British coal, i.e., Russia lost almost half of all the coal she needed, namely, that out of the 2,086,000,000 poods of the total expenditure of the state in 1913, the Donets basin that remained at Russia’s disposal could produce only 1,197,000,000 poods.

All strenuous attempts to increase the extraction and export of coal from the Donbass and thus cover the lost sources of supply, of course, could lead to nothing.

Such a severe blow, inflicted on the integral organism of the country’s economy, is only slowly, consistently, over months and years, transmitted deeper and deeper, first absorbing the accumulated reserves and, finally, paralyzing the entire economy, and in particular even the most residual production of coal, oil and firewood in the areas remaining at the disposal of Russia.

“Taking care of fuel”

As stated in the report of the People’s Commissariat of Communications, great efforts were made to alleviate the acuteness of the fuel problem

“Taking care of fuel is becoming the main issue of the country’s existence; A Central Committee for the Distribution of Fuel was organized under the chairmanship of the Minister of Railways, and a quota of 120,000,000 poods a month for the export of coal from the Donbass was appointed: at first the export was actually very close to this, namely, 110,000,000 poods (now 23,000,000 poods).

In order to cope with the disaster further, a number of urgent complex measures were taken, which in the end yielded significant results, prevented, suspended, and prolonged the inevitable destruction of the country’s productive forces.

1) It is not enough to say that millions of poods of coal have been exported per month, it must be said, what kind of coal. The coals of Donetsk are mainly anthracite, which, to our shame, we do not know how to work with, while America uses it magnificently. I had to learn and teach the stokers to work on anthracite. With the participation of Professors Shchukin and Kirsch, the most successful mixture of anthracite and coal for heating steam locomotives (one third of anthracite and two thirds of coal) was calculated. First of all, this mixture began to be used on the Catherine and Southern roads, then near the extraction of anthracite and on other roads. The struggle for this “innovation” was stubborn; Often the drivers threw anthracite fines from the locomotive, along the sides of the embankment of the railway. roads. canvas, declaring that anthracite does not burn, is not suitable as fuel on steam locomotives. (Anthracite is the best of all kinds of coal, the hottest, but it is really extremely difficult to ignite at the beginning.) Those who drove along the Nikolaevskaya road at that time could see its canvas, strewn on the sides with heaps of anthracite — trifles. But still, after 4 months, 10 roads switched almost completely to heating with the above-mentioned mixture, the consumption of anthracite on them was equal to 20% of the total fuel consumption, i.e. almost corresponded to the percentage composition of the mixture.

2) The “station” boilers of buildings and wagon boilers were converted to anthracite heating.

(3) A requisition of firewood was carried out (“requisition” is now considered “Bolshevism”) in a 30-verst strip along the railway, which yielded 330,000 cubic fathoms.

4) The development of firewood by the glands themselves has been intensified. and contractors, chiefly the Forest Department, which gave the roads another 100,000 cubic fathoms.

5) For the first time, attention was drawn to the “gray coal” peat, which had been neglected until then… Experiments with peat heating of steam locomotives were carried out in two ways — with briquettes and peat powder. The experiments turned out to be successful…

6) For the first time in history, coal consumption by consumers began to be accounted for, distributed and controlled; Also, for the first time, an accelerated centralized state settlement of all railways with mines supplying coal through the first recipient of coal from the mines, through the Administration of Southern Railways in Kharkov, was established.

7) Coal discharge into dumps has been reduced due to the tolerance of coal ash content from 15% to 20%.

8) A mixed railway-water delivery of coal from Donbass has been organized.

At the same time, as stated in the report, work was underway to expand the possibilities for the delivery of goods from the northern and Far Eastern ports:

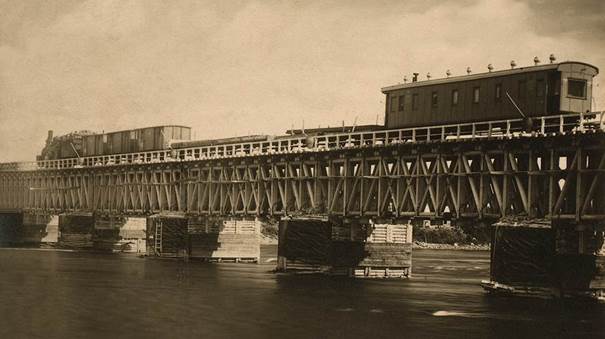

“A thin thread — a trickle, the Moscow-Arkhangelsk line, designed, as the last of the thinnest arteries, for negligible blood circulation, could pass only 70 wagons a day and suddenly turned out to be the only connecting thread of the center with Western Europe.

A grandiose, unique task in the world’s railway annals is being set and carried out: to build in one year a new railway to the Arctic Ocean, more than 1,000 versts long, through places where only a brave hero, a geographer-traveler, driven by love for new scientific discoveries, has passed before, where there was no habitation at all, where eternal night reigns for half the year and permafrost all year round. where a horse, having dragged a pack of 5 poods for 1 verst, already collapses in exhaustion, where the most elementary conditions not only of human, but even of tolerable animal existence were lacking, where even the English workers, with all their mechanical culture and severe disciplined endurance, could not build even 15 versts from Murmansk and, having gone on strike, abandoned their work; There, in this realm of the polar night, the construction was completed in exactly one year, or, more precisely, in one season of the polar bright “summer,” although this construction absorbed about 40,000 lives, either completely lost or crippled mainly by scurvy, typhus and rheumatism.

A similar task is being carried out on the Vologda-Arkhangelsk line, where this road is changed from a narrow gauge to a wide gauge in one year.

Finally, the capacity of the water-rail mixed route Severnaya Dvina-Kotlas-Vyatka is significantly increased.

As a result of all these conditions, 18,000,000,000 poods of coal, 4,000,000 poods of metals and other cargoes, and 3,000 military automobiles were exported in excess of the usual rate of goods in the first year (the usual rate is about a million poods a year). By the time of their completion (by the season of 1916) the total capacity of the three newly equipped railways and waterways was about 150,000,000 poods, or 430 wagons instead of 70 (i.e., 6 times the original capacity of the northern direction of Russia), which was as follows: 7,000,000 poods on the roughly built Murmansk railway. 28,000,000,000 poods on the Northern Dvina and 115,000,000,000 poods on the rewired Arkhangelsk railway.

It was difficult to hope for an increase in the capacity of the Siberian Railway because of its extreme length; Still, it was possible to increase the throughput there, namely 824 wagons per day instead of 708.”

“We couldn’t dissolve this deposit”

However, all these enormous efforts only slightly delayed, but did not stop the development of the devastation. Specialists of the People’s Commissariat of Railways claimed that the growth of problems was due to the division of rolling stock into civilian and army:

“At the time of the outbreak of the imperialist war, our railway network had a total length of about 66,000 versts. With the announcement of mobilization, the western network, lying west of the Petrograd-Vitebsk-Smolensk-Kiev–Yekaterinoslav line and south of the Donets basin and the Don region, was declared to be front-line roads, which came under the jurisdiction of the Military Field Administration; all the other roads formed the Eastern Region — the roads of the rear — which remained at the disposal of the Railway Administration of the Ministry of Railways. The western network was 22,000 versts. East — 44,000. There were a round number of 20,000 steam locomotives on the entire network (now 10,000). 500,000 wagons (now 300,000). This mobile fleet was also divided in proportion to the length of the network: one-third was listed behind the roads of the front, and two-thirds in the rear.

But in reality, as mentioned in the help, there was a different distribution:

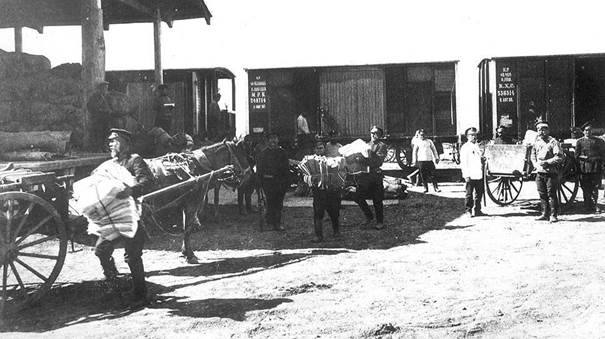

“The mobilization immediately forced the release of the wagons, the discarding of 32,000 wagons of ‘commercial’ cargo, and the delay of another 28,000 wagons without throwing the goods out of them. In total, immediately after the outbreak of the war, 60,000 wagons of cargo were withdrawn from the public use of the country. This figure of 60,000 wagons remained for the entire first year of the war (of course, not the same cargoes, but constantly changing); The railways were unable to dissolve this deposit. This figure is large in itself, however? Compared to the Japanese war, there were 200,000 wagons of cargo. The mobilization lasted only ten days, and then began the disarming of the adapted wagons; But normal commercial loading on all the roads, both front and rear, has fallen to 6,350 wagons per day, i.e., one-third of the pre-war loading of 20,000 wagons per day.

A total of 75,000 wagons out of 95,000 “equipped” at the beginning of mobilization were deployed on the railways of the Eastern network. All these armed-up wagons, however, went entirely to the same military and quartermaster transports.

Thus, an average of 145,000 wagons were diverted by direct military transport, i.e., in total, direct military transport on the roads of the eastern network occupied another third of the country’s rolling stock; i.e., only one-third of the country’s rolling stock remained for the ordinary needs of the rear.”

The army, as stated in the certificate, received everything it needed. In contrast to industry and the population:

“The flow of quartermaster’s cargo not only corresponded to the needs of the army, but even made it possible to accumulate 32 million poods of various quartermaster’s cargoes in the base depots.

On the other hand, in March 1915, the delivery of meat to Petrograd completely stopped; And in May, the supply of sugar almost ceased, despite the fact that the sugar campaign of 1914 was even more successful than the peaceful year of 1913, 150,000 wagons were transported, compared with 136,000 in 1913. The cotton campaign went so well, no worse than 1913.

As a result of the distance of transportation and other reasons, the export of coal from the Donets Basin also fell from 689,000,000 to 577,000,000 poods, in spite of the increase in the coal wagon fleet from 40,000 to 75,000, and the supply of ore to the metallurgical plants was greatly reduced.

The Ural mining industry was completely clogged with military transports flowing past it in a continuous stream; it was necessary to close the Perm direction for military transportation in order to make it possible to work for the defense of the Urals.”

They tried to make up for the lack of rolling stock in all possible ways:

“With the declaration of war, 43,000 new wagons and 1,500 locomotives were ordered from the Russian factories for 1915; According to the plan, another 40,000 wagons and 400 steam locomotives were to be ordered, but the Russian factories refused to take over this order because of the overload of their capacity. Part of it was taken by America, namely, 13,600 double Fox-Arbel cars, equal to our 26,320 cars, and all 400 locomotives of a particularly powerful type.

At the beginning of the war, the shortage of wagons and locomotives had to be compensated by a number of skilful measures to increase the expediency of their operation. These were as follows:

(1) The use of about 15,000 earthen platforms (usually idle in winter) for the transport of coal by building up the sides.

2) Allowance for loading 1,200 poods into a wagon instead of 1,000 p.

3) Disposal of special-purpose wagons, mainly for meat transportation.

4) Installation of block trains to reduce maneuvers on the way and facilitate their passage through railway junctions.

5) Running trains “after each other” at first in the form of normal, but one-way traffic with a delay in all oncoming traffic, then, without waiting for arrival, in 15 minutes one after another, and, finally, in a continuous belt of trains at intervals of 50-100 fathoms. and a speed of 5-10 versts per hour. The troop trains were thus delivered from Siberia 4 days ahead of schedule.

6) Introduction of heavier train trains, for which purpose modern, powerful types of steam locomotives were ordered…

(7) The use of pushers in sections with a difficult profile, which, after all, determine the carrying capacity of the entire road…

8) Reduction of wagon downtime, because the main life of a wagon, 70% of its time, consists in stopping, and not in movement: waiting for loading, under load; awaiting unloading, under unloading; awaiting repairs, under repair; but not on the move.”

As indicated in the report of the People’s Commissariat of Railways, newly invented methods of increasing the load of wagons were also used:

“For the transportation of lightweight hay, an ingenious method was invented to reload the wagon from below with rails going to the front, up to the full lifting power of the wagons.”

“Running and Getting Dirty”

But, as the specialists of the People’s Commissariat of Commissariat of Communications admitted with regret, all good initiatives did not yield results due to the human factor. An attempt to introduce continuous running of steam locomotives, when train crews were not assigned to a specific steam locomotive, led to a deplorable result:

“American incessant driving, with the lazy, slovenly attitude of almost every Russian to his duties, has led to the consistent start-up and defilement of all locomotives.”

But even worse was the occurrence of an acute shortage of wagons for commercial cargo:

“At the end of the first year, colossal speculation and railway bribery began everywhere on the basis of the wagon famine. Thousands of circulars, prohibitions on the direction of goods and their cancellation, closure and new exemption not only from military invasions, but also from spontaneous disturbances — evacuations, re-evacuations, the cluttering of all stations with quartermaster’s and military cargoes, insecurity of existence and hunger — all this created the possibility of the widest bribery, abuse, predatory theft of the people’s wealth; They even stole less than spoiled in order to be able to steal.

Instead of flying repairs, sand was poured into the axleboxes of the cars and then the car was uncoupled “on fire” or the car was braked too tightly, so that the wheels crawled along the rails and bondages got a pothole; The cargo was stolen, and the wagon was provided for a new load for a huge amount of money, having fixed it with flying repairs. The theft was carried out by a conspiracy, a gang of the stationmaster, and the repair team, or the train inspectors, and the train crew, and the compilers, and the gendarmes, and so on.

At the same time, the thieves were not embarrassed by the fact that there were no more wagon axles and bondages in the country’s reserve, and extremely quickly artificially wore out the last available resources. Nuts were rolled from the bodies of wagons and locomotives for sale, bolts were pulled out. What’s the matter if, after a while, the whole car crumbled into separate boards, which were burned at the stake? Such examples can be endlessly cited from the Russian reality, rich in the criminal past.”

The saddest thing was that it turned out to be much more difficult to eliminate the “devastation in the heads” than to restore the work of the railways after the war:

“All this, unfortunately, has recovered again now and is a terrible ominous sign of a serious illness in the country.”