When did the teachers live better: under the king, under the councils, or now?

I have already published two long articles on teachers’ salaries under the tsar and during the Soviet era. If you haven’t read it, the links will be at the end, I’ll just briefly retell the essence. It remains to talk about current salaries. I hope that teachers read me and will be able to correct me, as my personal experience may not correspond to the average.

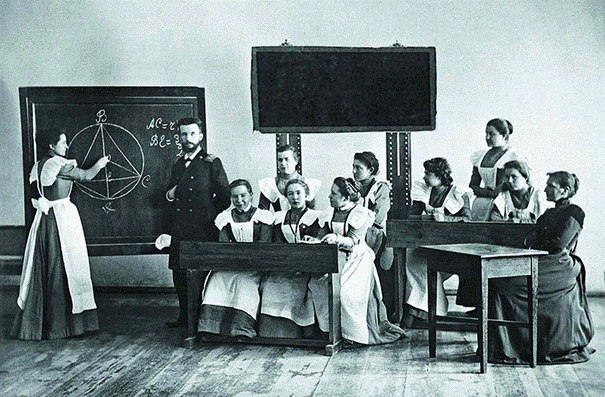

Under the Tsar

There are many legends about the tsar’s teachers. They say that they were fabulously rich, the profession was considered prestigious, they had many benefits, they were one of the few who received a pension on a par with the military. This is true, but only partially. The fact is that teachers in tsarist times had a hierarchy.

The fattest life was for science teachers (subject students) with higher education, who worked in gymnasiums and real teachers (analogues of our secondary schools and physics and mathematics classes, respectively). They were paid more than most other professions and were placed above officials.

Under Nicholas II, there was an educational boom. An experienced science teacher with a higher education in a gymnasium—there were few of them—could earn more in a month than an industrial worker earned in a year. Art teachers were paid about half as much, but still had the same benefits and privileges.

Gymnasium of the XIX century in Russia.

Many teachers were provided with free housing, reimbursed for utility bills, but most importantly, the teachers were civil servants. This imposed some restrictions on them, but on the other hand, they received a pension, salaries were indexed and it was possible to curry favor with a nobleman (personal and even hereditary), plus they received orders that gave an increase in salary and pension. Not a life, but a fairy tale.

Teachers of county schools (an analogue of our primary school) were paid several times less! Sometimes they were paid so little that they did not have enough money to rent a house, and teachers lived right in schools. And you have to understand that at that time schools had little resemblance to modern ones. They did not meet any sanitary standards, it was humid and cold there. Teachers earned chronic diseases (rheumatism, pneumonia, and so on) for 5-10 years of working in such conditions.

Of course, teachers of zemstvo, rural and parochial schools could not even dream of any privileges, pensions, orders, nobility and other privileges. In addition, training in such schools took place only in free time from field work, as a rule, from October to April. For the rest of the time, from May to September, teachers were not paid their salaries, and they were forced to write articles for magazines, work as janitors, be hired by the parents of their students to work in the fields, and so on. In general, you should definitely not envy their lives.

Tsarskoye Selo Gymnasium.

Another important point is that if the situation with the teachers of gymnasiums, pro-gymnasiums and colleges in the country was more or less equal and their situation at least did not deteriorate from the beginning of the 18th century until the revolution, then the salaries of zemstvo teachers were close to beggars and strongly depended on the province. As a rule, the farther away from St. Petersburg and Moscow, the poorer the salary.

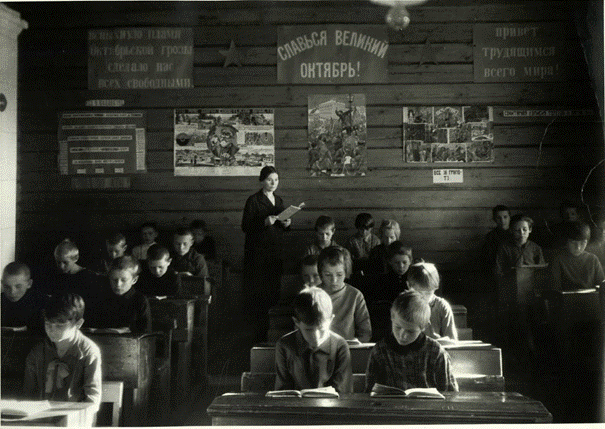

Under the advice

In spite of Lenin’s words that the teacher must be placed on a height on which he has never stood, does not stand, and cannot stand in bourgeois society, this has not been achieved.

Teachers in the USSR fared best at the very end, after Chernenko’s April 1984 reform. For the first time since tsarist times, teachers began to live better than workers, builders, and many other professions. The average salary of a teacher with experience, checking notebooks, classroom management, and so on was about 1.5 times higher than the average salary of an engineer at a factory. Not 12 times, as in the time of the tsar, of course, but also nothing.

Geometry lesson in a Soviet school.

The good news was that teachers’ salaries were about the same across the country. But it is necessary to take into account the fact that there were practically no teachers without education, and secondary schools were an analogue of royal gymnasiums.

However, let’s not forget that the USSR is not just the 1980s. After the revolution, teachers often worked on a piece-rate basis, and sometimes even for food. At the same time, there was not much difference between gymnasium teachers and a rural teacher of a public school without education. The revolution equalized everyone. But I equalized not on the upper level, but on the lower one.

Up until the 1940s, the work of a teacher was extremely low-paid, only collective farmers received less. It was only enough for nourishment without frills. A builder was paid 2-2.5 times more than a teacher.

Soviet school in the 30s.

After the war, the situation got a little better, but teachers were still paid significantly less than construction workers, doctors, factory workers, and factory workers. The authority of the teacher grew, but in terms of money, teachers remained obscenely poor until the mid-1960s compared to those whose children they gave a start in life.

In 1964, for the first time, the teacher’s salary was equal to the salary of the average factory worker and gradually increased. On the whole, though, up until 1986, which I have already written about, teachers lived mediocrely. A little more factory workers were paid, but there were fewer builders and engineers.

What’s Today

By today, I mean the last 30 years. But I’m not going to say much here, you know. In the 1990s, teachers quit their jobs en masse and went to the market because many schools didn’t pay at all.

Teachers’ strikes in the 90s.

Then the situation began to improve a little, but here I would like to hear the opinions of those who worked as a teacher 20-20 years ago. As far as I know, it was almost impossible to live on a teacher’s salary alone. It was enough for meagre food not to die of hunger, but there was no need to talk about a decent salary for the teacher’s work.

Today, the average salary of a teacher in the country is 45,832 rubles. But the spread is huge. In Moscow and the northern and remote regions (Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Magadan Region, Sakhalin), teachers’ salaries are close to 100,000 rubles per month. In other regions, it is often half the average. According to official data, teachers in Ingushetia, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia receive the least. Salaries in rural schools are even lower.

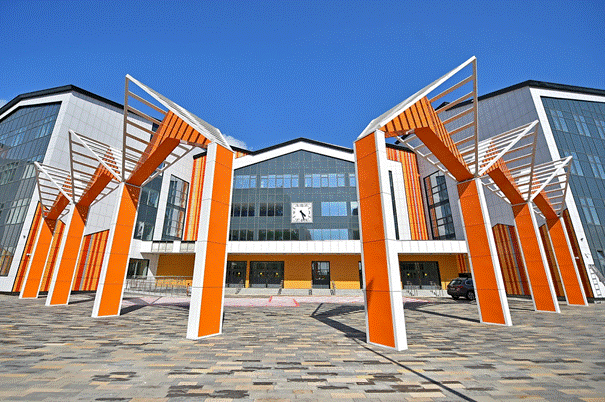

The largest school in Russia at ZIL

For comparison, the average salary in the country, according to Rosstat, is 56,545 rubles. That is, the teacher’s work is rated below average. However, according to statistics, the average salary of an engineer is 49,700 rubles, a doctor – 80,800 rubles, a driver – 43,600 rubles, a programmer – 120,000 rubles, a janitor – 19,200 rubles.