What was Mein Kampf about, and why was the book turned a blind eye?

If you follow Hitler’s path to power, it is very difficult to believe that he was able to occupy such a high position in Germany and to influence history in such a way. On his way to dictatorship and ultimately war, there were so many “hit or miss” situations that it’s hard to decide whether it was either incredible luck or a cruel whim of fate. It really was a one-in-a-million chance. In this series of articles, we will look at how Hitler managed to gain a dominant position in Germany at that time. In this text, we will talk about the first turning point, the publication of Mein Kampf.

What was Mein Kampf about?

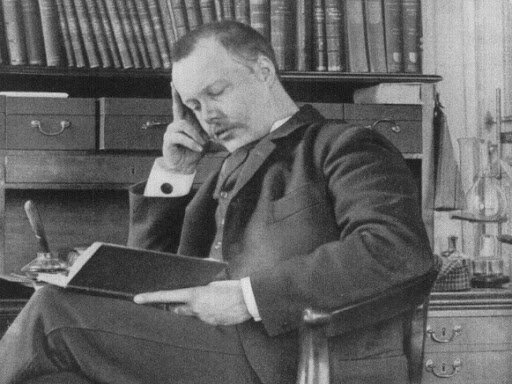

When it was first published, Mein Kampf (Mein Kampf in Russian) sold terribly. In 1925, 9,473 copies were sold, and then sales decreased every year. Hitler, however, was not particularly known at the time. While imprisoned in the Landsberg fortress after the Beer Hall Putsch, he dictated a book to Rudolf Hess. In it, he expounded his political views. If the book had been looked at earlier, Hitler might never have been in power. Because he described in detail the “New Order” that he was going to introduce in Germany, and then in the whole world. And any sane person would have had the hairs on the back of their head from this vision.

In prison, Hitler was kept in excellent conditions – acquaintances and friends were admitted, to one of whom he dictated “Mein Kampf”

So what were his views? The state must be based on race and unite all Germans, including those outside the Reich. Hitler believed that the strongest wins, and this is decided in the eternal struggle, which is the basis of life. And, of course, he considered only the Aryans to be the strongest. He considered all the achievements of culture to have come from the Aryans. All other nations were inferior and had to occupy a subordinate position. He directly referred to the Slavic peoples as slaves and forced laborers. Hitler attributed the fall of Germany to the fact that the Aryans did not keep their blood pure and mixed with lower peoples. And this could only be changed if Germany regained its dominant position in the world.

Moreover, the purity of the race must be monitored now. Healthy people had to give birth to children, sick and infirm parents had to refuse to do so. Hitler regarded the family as a means of enlarging and preserving the race, that is, of strengthening the strength of the race. At the head of this race was to be the Führer, the strong hand that governs the state. There must be absolute obedience to him, and he has full power. Hitler did not accept democracy in any form and considered it a relic of the past.

The so-called Lebensraum, or “living space”, is highlighted in green. In Hitler’s opinion, these were the territories that the Third Reich was to seize and enslave their populations

Germany must also receive a vast territory in the East as part of Lebensraum. Hitler wrote bluntly about the seizure of Russia. He believed that the Germans should follow in the footsteps of the Teutonic Knights and find a new land by the sword. Before that, however, Germany must get its hands on the adjacent lands to the east. What kind of land were they? Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. In the end, Hitler systematically captured them, opening the way to Russia.

Where did these views come from?

By the way, these views did not belong only to Hitler, they were shared by many Germans at that time. These views, in turn, were shaped by the theories of the French diplomat Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and the English aristocrat Houston Chamberlain.

Gobineau is one of the authors of the theory of racial inequality. He inspired Hitler in no small measure

For example, Gobineau believed that race was the key to understanding history and civilization: “The race question occupies a leading place among other problems…” Among the three main types of race—white, yellow, and black—he singled out the white race as superior. The real treasure of the white race was, in his opinion, the Aryans, the inhabitants of France, England, and Scandinavia, as well as the West Germans. It was the Germans that he considered to be the engines of civilization in the West, and this certainly flattered them.

Houston Chamberlain saw the Teutons as the saviors of mankind. This, too, pleased Hitler

Chamberlain wrote Principles of the Nineteenth Century, in which he pointed out the Teutons as the only hope for the salvation of mankind. His definition of a Teuton is vague, in general, but the Nazis chose to consider themselves Teutons, of course. The fate of every nation on the planet depended on the presence of Teutonic blood in its people. There is also a virulent anti-Semitism in Chamberlain’s work, although he considered Jesus Christ to be one of the great treasures of modern civilization. In his view, however, Jesus was not a Jew, but an Aryan. Since the Germans had inherited the best qualities of the Greeks and Aryans, they were to rule the world, after all. Shortly before his death, Chamberlain had praised Hitler, and it was only natural that the Englishman’s ideas should find a place in Mein Kampf

Why did they turn a blind eye to the book?

In Hitler’s first year as chancellor, sales of Mein Kampf reached one million copies. It became the bible of the German people, only it led them not to the light, but to a darkness full of suffering and horror. If those who finally installed Hitler as Chancellor had taken a closer look at this book, they would certainly not have put such a madman in charge. But they chose not to read the main work of the next ruler of Germany. They chose to turn a blind eye to the destructive program of action that he systematically and consistently implemented. Or perhaps they didn’t seriously believe that a person could do it. They underestimated Hitler.