First Prosecutor of the USSR. Not a lawyer, just an honest person

In the first years of Soviet power, there was a vacuum of professionals in all spheres. Despite the fact that old cadres were everywhere involved, many of them worked half-heartedly, sowed sabotage and outright harmed. At the same time, the Bolsheviks were throwing their ideological comrades on all fronts and directions, trying to patch up the sprawling Trishkin caftan.

If you look at the biographies of many prominent Bolsheviks, you will see that in the 1920s and 1930s, each of them took over many positions, and not at all on his own initiative. Where the Party will also send the Soviet government. And the ideological component was often more important than experience, knowledge and skills.

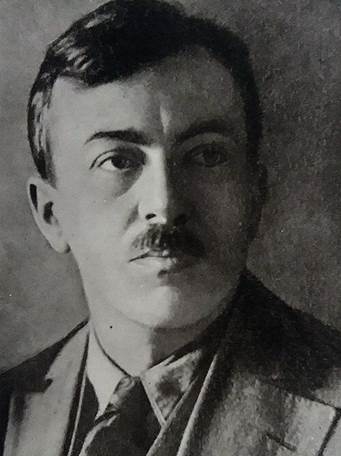

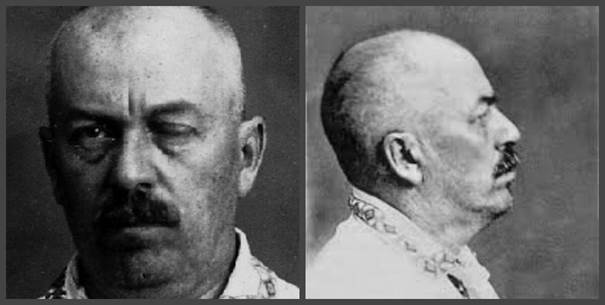

Ivan Alekseevich Akulov did not have a legal education, or even a higher education. Nevertheless, Ivan Akulov, an ardent revolutionary and participant in the Civil War, held important leadership positions in the party and state power.

Image source: uk.wikipedia.org

In the twenties, Akulov advanced along the party, trade union and state lines, but for more than two years he did not stay anywhere. Not because it didn’t work well. He worked well, but the party set new tasks for him.

He worked as a secretary of the Kyrgyz regional committee, then of the Crimean one, worked as chairman of the All-Ukrainian Council of Trade Unions, secretary of the All-Ukrainian Central Council of Trade Unions, was deputy People’s Commissar of the Russian Foreign Language of the USSR, member of the Presidium of the Central Control Commission.

In 1931, the party sent Ivan Alekseevich to work in the GPU, he was the first deputy chairman of the OGPU. In 1932, he again worked as a party worker: secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine in Donbass.

The decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR of June 20, 1933, which established the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR, was fateful for Akulov. And the next day, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov was appointed Prosecutor of the USSR.

Despite the fact that Akulov did not possess legal skills (the position was more political than functional), he shoveled through a mountain of books on jurisprudence, and his experience in the GPU helped him build a viable system of the Soviet prosecutor’s office.

He personally worked on an important legislative act for the country, the “Statute on the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR”, which defined the role and importance of the supervisory agency in the system of Soviet authorities. On December 17, 1933, the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR adopted this act.

The same decree abolished the Prosecutor’s Office of the Supreme Court of the USSR. Now the prosecutor’s office did not depend on the court, but was an independent department. The Prosecutor of the USSR was now appointed only by the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and was responsible only to the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR, the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and its Presidium.

Akulov’s employees recalled that, despite his high position, he held receptions for ordinary citizens, delved into their problems and complaints. Moreover, he has set up the work in such a way that all prosecutors are obliged to receive the population and promptly resolve citizens’ issues. And especially important complaints, testifying to gross violations of the law, Ivan Alekseevich took under his control.

With his subordinates, Akulov behaved simply, if necessary, he asked for advice from more experienced comrades, and did not disdain this.

As N. A. Orlov, a former employee of the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR, recalled:

“Akulov was in the full sense of the word a charming man, a man of a broad Russian soul. He loved life and nature. Going on vacation, he loved to travel, learn and show others new, beautiful places, was a subtle connoisseur of art, loved and understood music.

At home, he was the ideal of a family man, an extraordinarily loving father. He valued friendship highly, knew how to make friends, and was a loyal, reliable friend.”

At the same time, Akulov destroyed the entire existing system of the prosecutor’s office, which had previously shown itself to be effective. In March 1934, I.A. Akulov issued an order “On the restructuring of the prosecutor’s office in the center and in the regions”, according to which the prosecutor’s office moved from the functional principle of work to the production one.

Under Akulov, the division into general and judicial supervision was abolished, and all divisions were divided into enlarged sectors, which crumpled the work of the entire prosecutor’s office and made it less effective. This reform did not benefit the department.

First Prosecutor of the USSR. Not a lawyer, just an honest person

In the first years of Soviet power, there was a vacuum of professionals in all spheres. Despite the fact that old cadres were everywhere involved, many of them worked half-heartedly, sowed sabotage and outright harmed. At the same time, the Bolsheviks were throwing their ideological comrades on all fronts and directions, trying to patch up the sprawling Trishkin caftan.

If you look at the biographies of many prominent Bolsheviks, you will see that in the 1920s and 1930s, each of them took over many positions, and not at all on his own initiative. Where the Party will also send the Soviet government. And the ideological component was often more important than experience, knowledge and skills.

Ivan Alekseevich Akulov did not have a legal education, or even a higher education. Nevertheless, Ivan Akulov, an ardent revolutionary and participant in the Civil War, held important leadership positions in the party and state power.

Image source: uk.wikipedia.org

In the twenties, Akulov advanced along the party, trade union and state lines, but for more than two years he did not stay anywhere. Not because it didn’t work well. He worked well, but the party set new tasks for him.

He worked as a secretary of the Kyrgyz regional committee, then of the Crimean one, worked as chairman of the All-Ukrainian Council of Trade Unions, secretary of the All-Ukrainian Central Council of Trade Unions, was deputy People’s Commissar of the Russian Foreign Language of the USSR, member of the Presidium of the Central Control Commission.

In 1931, the party sent Ivan Alekseevich to work in the GPU, he was the first deputy chairman of the OGPU. In 1932, he again worked as a party worker: secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine in Donbass.

The decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR of June 20, 1933, which established the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR, was fateful for Akulov. And the next day, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov was appointed Prosecutor of the USSR.

Despite the fact that Akulov did not possess legal skills (the position was more political than functional), he shoveled through a mountain of books on jurisprudence, and his experience in the GPU helped him build a viable system of the Soviet prosecutor’s office.

He personally worked on an important legislative act for the country, the “Statute on the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR”, which defined the role and importance of the supervisory agency in the system of Soviet authorities. On December 17, 1933, the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR adopted this act.

The same decree abolished the Prosecutor’s Office of the Supreme Court of the USSR. Now the prosecutor’s office did not depend on the court, but was an independent department. The Prosecutor of the USSR was now appointed only by the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and was responsible only to the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR, the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and its Presidium.

Akulov’s employees recalled that, despite his high position, he held receptions for ordinary citizens, delved into their problems and complaints. Moreover, he has set up the work in such a way that all prosecutors are obliged to receive the population and promptly resolve citizens’ issues. And especially important complaints, testifying to gross violations of the law, Ivan Alekseevich took under his control.

With his subordinates, Akulov behaved simply, if necessary, he asked for advice from more experienced comrades, and did not disdain this.

As N. A. Orlov, a former employee of the Prosecutor’s Office of the USSR, recalled:

“Akulov was in the full sense of the word a charming man, a man of a broad Russian soul. He loved life and nature. Going on vacation, he loved to travel, learn and show others new, beautiful places, was a subtle connoisseur of art, loved and understood music.

At home, he was the ideal of a family man, an extraordinarily loving father. He valued friendship highly, knew how to make friends, and was a loyal, reliable friend.”

At the same time, Akulov destroyed the entire existing system of the prosecutor’s office, which had previously shown itself to be effective. In March 1934, I.A. Akulov issued an order “On the restructuring of the prosecutor’s office in the center and in the regions”, according to which the prosecutor’s office moved from the functional principle of work to the production one.

Under Akulov, the division into general and judicial supervision was abolished, and all divisions were divided into enlarged sectors, which crumpled the work of the entire prosecutor’s office and made it less effective. This reform did not benefit the department.

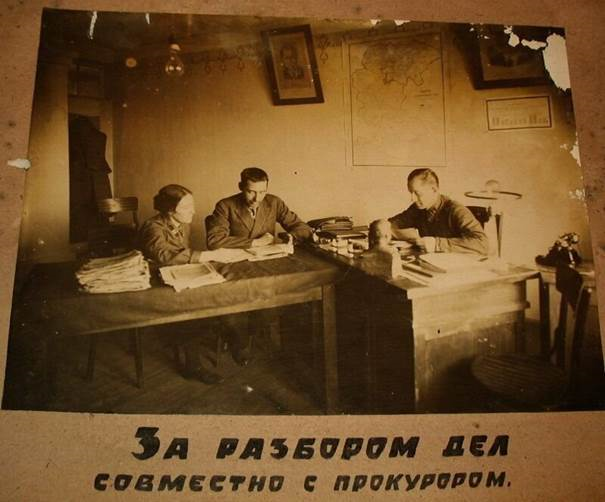

Image source: open source

Nevertheless, Akulov did a lot of useful things in the work of the prosecutor’s office, sought to get rid of red tape and bureaucracy, fought bureaucracy, introduced collegial operational meetings at all levels, and strengthened personal responsibility for the work of each prosecutor.

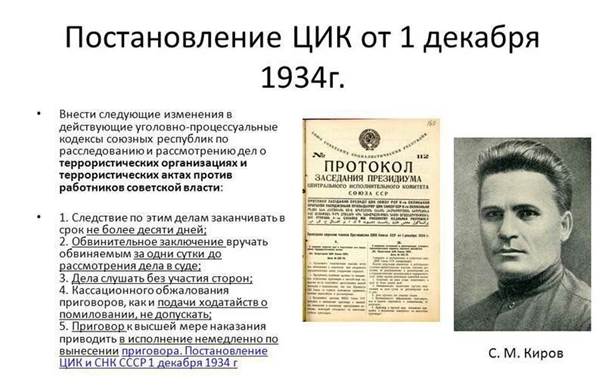

On December 1, 1934, in Smolny, the communist L. Nikolaev shot at the secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Leningrad Regional Committee, the communist S. Kirov. This date became an impetus for the intensification of the repressive actions of all law enforcement agencies of the state.

Nikolaev was detained, and the investigation began. And that’s where Akulov made a mistake. It can be said that the prosecutor’s office was completely removed from this, and the NKVD, at the instigation of Comrade Stalin, completely took it under its control.

People’s Commissar Yagoda was given “special powers”, but Akulov remained silent, and the law was violated for the first time. Formally, Ivan Alekseevich and his deputy Vyshinsky, investigator Sheinin, signed the testimonies, but signed ready-made interrogation protocols, knocked out by the NKVD officers.

And this was the prototype of the flail, which in 1937 turned into total lawlessness, Moloch.

And when the resolution of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of December 1, 1934 “On Amendments to the Criminal Procedure Legislation” was adopted, which formalized the terms of investigation in especially important cases, untied the hands of NKVD officers and judges, the case was heard without the participation of the parties, and the verdicts were brought immediately – Akulov also remained silent. And this was another stage leading to total lawlessness. And it was impossible to correct the mistake.

Moreover, Akulov was not just silent. On December 8, 1934, together with the Chairman of the USSR Court, A. Vinokurov, he signed the Directive on the practical application of the decree of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of December 1. This Directive was inherently criminal and violated all principles of justice, since it gave retroactive effect to the law of 1 December 1934. extending it to those acts that were committed prior to its adoption.

On March 3, 1935, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov was relieved of the post of Prosecutor of the USSR in connection with the transfer to another job (he was appointed Secretary of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR). It was a clear downgrade. Despite his diligence, Akulov did not suit the top leadership of the party as the Prosecutor of the USSR.

In May 1937, the NKVD of the USSR, together with a group of top military commanders of the Red Army, arrested I. Yakir, a friend of Akulov. On June 11, 1937, the flail in the form of the Special Presence of the All USSR sentenced all the defendants to the VMN. Mass arrests began in the Red Army. All the acquaintances of the “conspirators” were arrested, as well as their acquaintances, and circles dispersed throughout the country.

I.A. Akulov was relieved of his post as secretary of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR.

N.I. Shapiro (Akulov’s wife) recalled:

“In the last few days this calm, balanced man had reached such a degree of moral exhaustion that he was unable to write a letter to the Central Committee. For him, everything that happened to him was incomprehensible and the questions “who needs this” and “why?” repeatedly broke down.

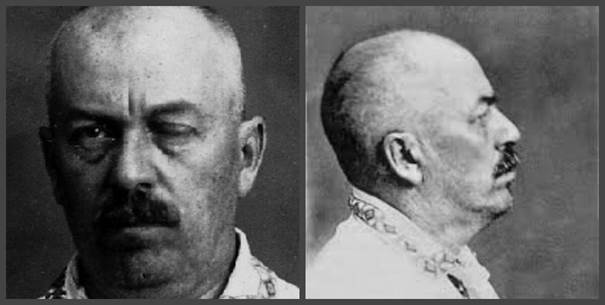

On July 23, 1937, Akulov was arrested at his dacha by the NKVD and placed in the Lefortovo prison.

After several days of interrogation, Akulov pleaded guilty to participation in a Trotskyite counter-revolutionary organization.

From the record of the interrogation of August 17, 1937:

“I, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov, until the day of my arrest in 1937, i.e., for ten years, was a member of an underground Trotskyite organization, in its ranks I carried on active work against the leaders of the CPSU (Bolsheviks) and the Soviet government, against the Soviet power. Besides, I didn’t think my accomplices had betrayed me. After all, more than a year has passed since the arrest of Golubenko, Loginov and others, and all this time I have continued to be engaged in responsible party and state work.

My hopes for the resilience of the members of the organization were not justified. So it’s useless to dodge. I am ready to answer sincerely all questions of interest to the investigation concerning the activities of the Trotskyite organization and myself personally as a member of it.”

At the court hearing on October 29, 1937, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov retracted his previous testimony. He pleaded not guilty. When asked why Akulov wrote a statement with a confession to investigator Alman, Akulov replied that the confession was given “in a state of loss of will.” Akulov went on to say that he had never been a Trotskyist, that he had always fought against them, and that he could not have been a wrecker, a terrorist, or a traitor to the motherland.

The verdict of the court is capital punishment with confiscation of property. The sentence was carried out the next day.

Akulov’s wife, Nadezhda Shapiro, was evicted from the mansion of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR together with her young children and ended up in a workers’ barracks. In November 1937, N.I. Shapiro was sent to a corrective labor camp (Temlag, Mordovian SSR) for a period of 8 years.

On December 16, 1946, a special meeting added another 5 years of exile to her as a “socially dangerous element.” After the exile, Shapiro lived in the Karaganda region, where her eldest son Gavriil was exiled. The family of the revolutionary Akulov was completely destroyed.

But Shapiro did not give up hope of rehabilitating her husband. In June 1954, she wrote a letter to the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR G. Malenkov, and he gave the Prosecutor General of the USSR R. Rudenko the task of looking into it.

On December 18, 1954, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR overturned the verdict against I.A. Akulov, and the case was terminated “for lack of corpus del

icti”.

Image source: open source

Nevertheless, Akulov did a lot of useful things in the work of the prosecutor’s office, sought to get rid of red tape and bureaucracy, fought bureaucracy, introduced collegial operational meetings at all levels, and strengthened personal responsibility for the work of each prosecutor.

On December 1, 1934, in Smolny, the communist L. Nikolaev shot at the secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Leningrad Regional Committee, the communist S. Kirov. This date became an impetus for the intensification of the repressive actions of all law enforcement agencies of the state.

Nikolaev was detained, and the investigation began. And that’s where Akulov made a mistake. It can be said that the prosecutor’s office was completely removed from this, and the NKVD, at the instigation of Comrade Stalin, completely took it under its control.

People’s Commissar Yagoda was given “special powers”, but Akulov remained silent, and the law was violated for the first time. Formally, Ivan Alekseevich and his deputy Vyshinsky, investigator Sheinin, signed the testimonies, but signed ready-made interrogation protocols, knocked out by the NKVD officers.

And this was the prototype of the flail, which in 1937 turned into total lawlessness, Moloch.

And when the resolution of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of December 1, 1934 “On Amendments to the Criminal Procedure Legislation” was adopted, which formalized the terms of investigation in especially important cases, untied the hands of NKVD officers and judges, the case was heard without the participation of the parties, and the verdicts were brought immediately – Akulov also remained silent. And this was another stage leading to total lawlessness. And it was impossible to correct the mistake.

Moreover, Akulov was not just silent. On December 8, 1934, together with the Chairman of the USSR Court, A. Vinokurov, he signed the Directive on the practical application of the decree of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR of December 1. This Directive was inherently criminal and violated all principles of justice, since it gave retroactive effect to the law of 1 December 1934. extending it to those acts that were committed prior to its adoption.

On March 3, 1935, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov was relieved of the post of Prosecutor of the USSR in connection with the transfer to another job (he was appointed Secretary of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR). It was a clear downgrade. Despite his diligence, Akulov did not suit the top leadership of the party as the Prosecutor of the USSR.

In May 1937, the NKVD of the USSR, together with a group of top military commanders of the Red Army, arrested I. Yakir, a friend of Akulov. On June 11, 1937, the flail in the form of the Special Presence of the All USSR sentenced all the defendants to the VMN. Mass arrests began in the Red Army. All the acquaintances of the “conspirators” were arrested, as well as their acquaintances, and circles dispersed throughout the country.

I.A. Akulov was relieved of his post as secretary of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR.

N.I. Shapiro (Akulov’s wife) recalled:

“In the last few days this calm, balanced man had reached such a degree of moral exhaustion that he was unable to write a letter to the Central Committee. For him, everything that happened to him was incomprehensible and the questions “who needs this” and “why?” repeatedly broke down.

On July 23, 1937, Akulov was arrested at his dacha by the NKVD and placed in the Lefortovo prison.

After several days of interrogation, Akulov pleaded guilty to participation in a Trotskyite counter-revolutionary organization.

From the record of the interrogation of August 17, 1937:

“I, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov, until the day of my arrest in 1937, i.e., for ten years, was a member of an underground Trotskyite organization, in its ranks I carried on active work against the leaders of the CPSU (Bolsheviks) and the Soviet government, against the Soviet power. Besides, I didn’t think my accomplices had betrayed me. After all, more than a year has passed since the arrest of Golubenko, Loginov and others, and all this time I have continued to be engaged in responsible party and state work.

My hopes for the resilience of the members of the organization were not justified. So it’s useless to dodge. I am ready to answer sincerely all questions of interest to the investigation concerning the activities of the Trotskyite organization and myself personally as a member of it.”

At the court hearing on October 29, 1937, Ivan Alekseevich Akulov retracted his previous testimony. He pleaded not guilty. When asked why Akulov wrote a statement with a confession to investigator Alman, Akulov replied that the confession was given “in a state of loss of will.” Akulov went on to say that he had never been a Trotskyist, that he had always fought against them, and that he could not have been a wrecker, a terrorist, or a traitor to the motherland.

The verdict of the court is capital punishment with confiscation of property. The sentence was carried out the next day.

Akulov’s wife, Nadezhda Shapiro, was evicted from the mansion of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR together with her young children and ended up in a workers’ barracks. In November 1937, N.I. Shapiro was sent to a corrective labor camp (Temlag, Mordovian SSR) for a period of 8 years.

On December 16, 1946, a special meeting added another 5 years of exile to her as a “socially dangerous element.” After the exile, Shapiro lived in the Karaganda region, where her eldest son Gavriil was exiled. The family of the revolutionary Akulov was completely destroyed.

But Shapiro did not give up hope of rehabilitating her husband. In June 1954, she wrote a letter to the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR G. Malenkov, and he gave the Prosecutor General of the USSR R. Rudenko the task of looking into it.

On December 18, 1954, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR overturned the verdict against I.A. Akulov, and the case was terminated “for lack of corpus delicti”.