Why are gypsies so disliked? History of the Romals

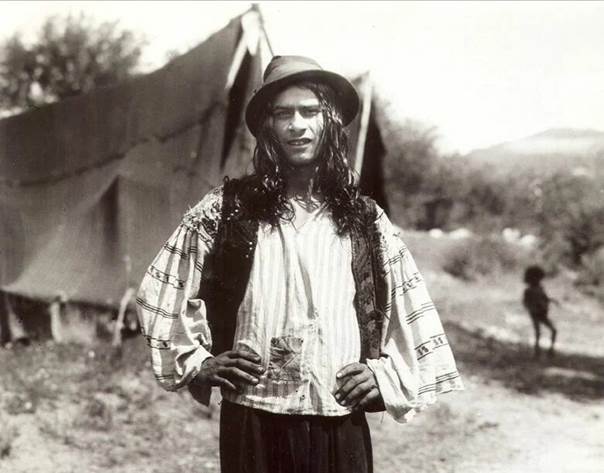

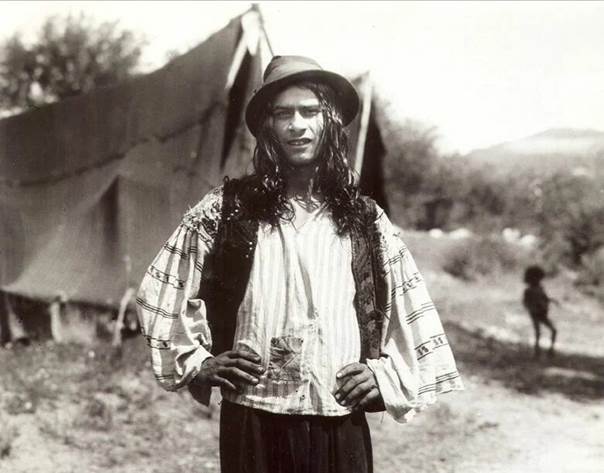

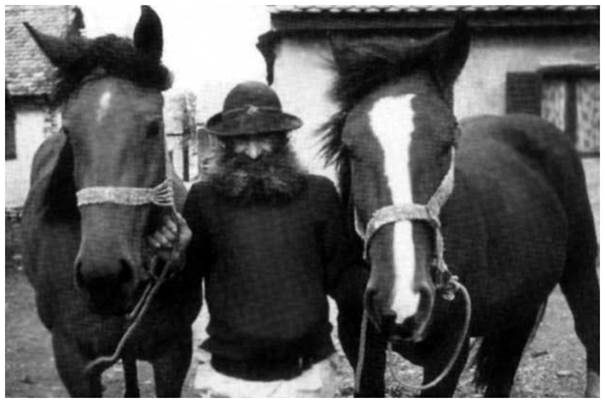

Perhaps many of us have some idea of this ethnic group, perhaps even influenced by the image of a colorfully dressed gypsy beggar at the train station.

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg. The Roma are a unique group that lives among us in our cities and manages to distance themselves from global civilization, preserving their old customs and traditions even in the 21st century. They are so independent that their numbers can only be estimated approximately, as they have traditionally distrusted the authorities. For example, there are potentially about 220,000 in Russia, but some demographers believe that these figures are underestimated, and the total number of Roma in Russia is two to three times higher. In fact, the Roma have built their own parallel society, and our society is in no hurry to integrate them to such an extent that some researchers suggest that there is an unofficial apartheid for the Roma in Russia.

Today we will talk about how the Roma came to life, where they came from, how they ended up in Europe and Russia, what they had to go through on their way, about their traditions, customs and occupations, and, finally, why it is so difficult for Roma to find their place in the modern world. Gypsies have become such an integral part of our world that it is difficult to imagine a world without them. However, historically, the Gypsies appeared as a people not so long ago, and the origin of the Gypsy people remained a mystery for a long time. The problem is that even the Roma themselves have been wandering for so long that they have lost track of where their homeland is. According to gypsy legends, their people are eternal nomads who do not have their own land. For example, in Perm, the local Gypsies had the following legend: “When Jesus was walking along the road, they were celebrating a wedding, and God said: ‘Stop, stop, Gypsies, I am God, I am Jesus, the Son of the Father,’ but the Gypsies did not notice God. However, we do not have our own land. Every nation has its own land, even the smallest. It should be noted that Jesus is present in this legend because most modern Gypsies are Christians.

The Roma living in Russia are mostly Orthodox Christians. In Poland or Hungary, however, they are predominantly Catholic. Roma in Crimea and Central Asia are Muslims, but they are a minority. When the Gypsies arrived in Europe in the 15th century, they were already Christians. Therefore, they presented themselves as pilgrims who gave alms to the Pope, and called themselves princes of Little Egypt or Syria. The Roma claimed that they were punished by having to travel to Europe as pilgrims because they had apostatized from the Christian faith. Later, the meaning of the term “Little Egypt” was forgotten, and everyone began to believe that the Gypsies originated from Egypt itself. This opinion is reflected in the names given to the Romani people in different languages, for example, in the English word “gypsy”, which comes from “Egyptian”, or in the Spanish word “gitano”, which means “Egyptian”. The Hungarian word “pharaoh-epic” even suggests that the Gypsies were descendants of the pharaohs. Russian peasants also called the Gypsies “the tribe of the pharaoh”. This belief persisted until the late 18th century, when linguists discovered that the Romani language had much in common with languages spoken in India, such as Sanskrit, Hindi, and Punjabi. The Romani language belongs to the Indo-Aryan group of languages, which is the only Indo-Aryan language outside of India.

The prevailing theory is that the Gypsies are descendants of a caste in India called the “untouchables” who were itinerant magicians, dancers, and blacksmiths. Interestingly, the Roma in the Middle East, i.e. in Syria and Turkey, still call themselves “home”. Linguists believe that the word “house” gradually developed from the original word “domba”, which the Roma call themselves in Armenia. Eventually, the word “domba” turned into “crowbar,” which is what the Gypsies call themselves in some countries. Finally, the word “lom” turned into the word “gypsy”, which is what gypsies are called in Europe and Russia. The idea that the Gypsies could have come from India is not implausible, given that India has always been connected to European and Islamic civilization through trade and travel. The Indian people have traveled extensively throughout history, including to the Middle East. They even appeared in Babylon and beyond during the ancient Persian Empire. Therefore, the idea that some Indians may have settled in Europe is plausible. Moreover, the appearance, language, and customs of the Gypsy people are similar to those of the inhabitants of Northern India, which further supports this theory. There are many other examples of Gypsy culture of Indian origin, which I will discuss later. The most convincing evidence, however, in my opinion, is the Roma people’s own traditions, which they claim are rooted in India.

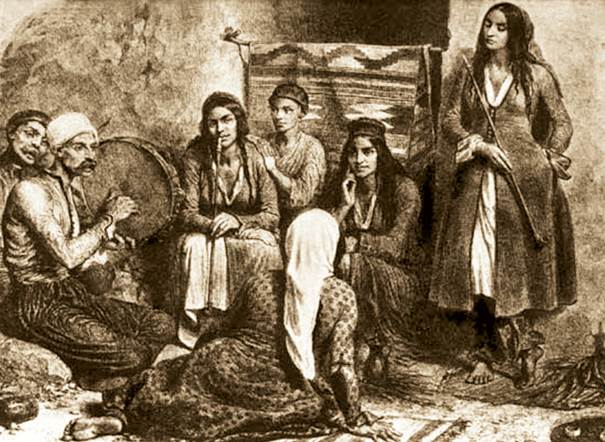

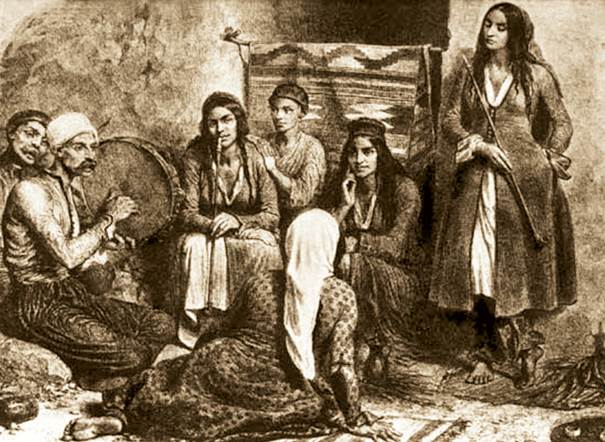

In India, and specifically in the Punjab, it is now safe to say that the hypothesis of the origin of the Gypsy people from India has been proven. However, it is still not fully understood how the Roma got to Europe. There are some historical sources that can be linked to the Gypsy people, such as the Persian poem Shahnameh, which tells how the Shah of Persia invited thousands of musicians from India to his country in the 5th century AD, around the same time that Rome was conquered. But that’s just a legend. The main hypothesis is that the ancestors of the Gypsies left India and moved west between the 6th and 10th centuries AD. It is based on linguistic data, as the Roma language has many loanwords from Persian and Greek, but almost no Arabic loanwords, suggesting that the Roma somehow escaped contact with the Arab conquerors. At some point, the Roma became so numerous that laws were passed restricting their activities. At the beginning of the 14th century, the Patriarch of Constantinople issued a decree forbidding believers to allow gypsy snake charmers, bear leaders, magicians and fortune-tellers into their homes. The first description of a gypsy camp comes from the Franciscan monk Simon Simeonis, who in 1322 met gypsies living in caves and flat tents in the Arabic style near the city of Heraklion on the island of Crete. For example, in 1491, the German traveler Dietrich von Schachtmann described a gypsy settlement near the town of Madona in the Peloponnese, where there were many small shacks in which lived the so-called Roma, who were very poor and almost all blacksmiths. In late Byzantium and its environs, there were so many Gypsies that in some places they even gained self-government. For example, on the island of Corfu, which was then ruled by Venice, there was a gypsy patrimony, where only gypsies lived according to their own laws. This fiefdom lasted until the end of the Republic of Venice in the 19th century. The tradition of granting self-government to the Roma continued until the 18th century in many countries. Other countries received a flat tax on this population, but allowed them to live as they wished.

In Russia, for example, the institution of Roma atamans, who were both tax collectors and heads of Roma self-government, survived until the time of Catherine II in the 14th and 15th centuries. As Byzantium began to crack at the seams and the Balkan Peninsula was engulfed in bloody wars, the Gypsies moved on to Europe. The Roma were recorded in Serbia in 1348, appeared in Bulgaria in 1378, Wallachia in 1385, Hungary in 1422, and in Germany, the Czech Republic, France, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands in the 15th century.

According to the European chronicles of the time, the Gypsies introduced four chieftains to Europe, whom the Europeans called kings: Sinti, Michael, Andrew, and Punuel. At that time, there was a story that the Gypsies were allegedly making a pilgrimage to the Pope in Rome. At first, the Gypsies were held in high esteem, primarily because they were pilgrims, and secondly, because they paid handsomely for their stay. However, from the second half of the 15th century, accusations that the Gypsies were Turkish spies began to be heard more and more often. Gypsy women were accused of being witches and apostates because they practiced forbidden practices such as divination among Christians.

Gradually, laws against the Gypsies began to appear in Europe, just as the German principalities passed laws against the Jews, where it was even permissible to kill any Gypsy you met on the street. However, the English dictator Oliver Cromwell put the sale of gypsies into slavery on American plantations, and they ended up in America. However, in most cases, things were not so radical. After all, unlike the Jews, the Gypsies were at least formally considered good Catholics, or rather Orthodox. Often, attempts were made to assimilate Roma children, they were even given to Christian families to be raised, and young men were taken into the army. However, these measures did not help much, and by the beginning of the 16th century, the Gypsies had settled in Spain, England and the Scandinavian countries. However, they still retained a marginal status and did not fit into society. Why did the Roma preserve their independence and uniqueness for centuries without assimilating with the surrounding peoples? Perhaps it had to do with their language. It’s both a yes and a no.

The language situation of the Roma is better than that of the Jews, who spoke dozens of completely different languages before the artificial revival of Hebrew in the 19th century. In principle, the majority of Roma retain their Romani language as their primary language. However, it can hardly be called a single language. Linguists believe that all Roma in Europe, from Spain to Russia, speak the same language but different dialects. The nuance is that over the centuries the Gypsy dialects have diverged so much from each other and absorbed words from the languages of the surrounding peoples, from Russian and Ukrainian to Hungarian and Romanian, that even the basic terms in their languages can differ significantly. At present, all European Roma are divided into four groups on the basis of language. The northern group includes the Gypsies of Western and Northern Europe, from France and Great Britain to the Urals.

This group includes German and Italian Gypsies, Russian Gypsies living in Poland, Belarus, the Baltic States and Central Russia, as well as Finnish Calderaches and British Travellers, which literally means “travellers”. By the way, if the term “Russian gypsies” reminds you of the movie “John Wick”, then this is for a reason. In addition to the fact that the protagonist is associated with the Belarusian Roma mafia, after the collapse of the USSR, Belarusian Roma prefer to be called Belarusian Gypsies rather than Russian Gypsies. Be that as it may, the film depicts a world with a lot of Gypsy traditions. For example, paying with gold coins is also a gypsy tradition. Such money has a sacred meaning for the Gypsies, and they use it to pay the bride price.

They are descendants of the same wave of 15th-century migration that swept through European countries, including Russia. In other ways, these Gypsies are very different. They lived in developed European countries, and it affected them a lot. For example, among the Russian Gypsies, the Russian Roma are considered to be the most educated – by Roma standards, of course. These Roma are also considered to be the most assimilated. For example, much of the vocabulary of the Russian Gypsies is borrowed from Russian, the Sinti from German, and the British Gypsies borrowed English and Welsh so much that linguists speak of an English-Romance language. By the way, since we have touched upon the topic of British Gypsies, it is necessary to say a few words about the Gypsies who appear in Guy Ritchie’s film “Snatch”. They’re not gypsies at all. Traditionally, in the UK, two different peoples are referred to as Gypsies or Travellers. In England live the Gypsies, or Romani, who migrated to the island from the continent sometime in the late 16th century. They speak a dialect of Romani with English and Welsh loanwords and look like the regular Gypsies we know, with dark skin and dark hair. There are also Irish Travellers, to which Brad Pitt’s character in the film belongs. Historians debate their origins, but the main theory is that they are descendants of Irish people who lost their homes and lands during Oliver Cromwell’s invasion of the island in the 18th century and became wanderers, gradually adopting a lifestyle virtually indistinguishable from that of the Gypsies, to the point that they became confused with them and were eventually given the same name.

The Irish government even has a dedicated office to protect the rights of the Traveller community, which has around 15,000 people in the UK, 30,000 in Ireland and 40,000 migrating across the US. The number of Gypsies in the UK, not counting the Travellers, is estimated to be over 200,000. The largest Roma populations are found in Spain and France, with about 1.5 million people each, as well as in the United States, where about a million people consider themselves descendants.

As for the other three Roma groups, they did not stray far from the Balkans during their migration. This does not mean that the Roma completely left the territories of the former Byzantine Empire in countries such as Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, Turkey, Albania and others. Several hundred thousand so-called Balkan Roma still live there, with the most densely populated areas being the Turkish provinces of Armi, Sary-Sipahi and others, home to more than 2.5 million people. There are officially about 300,000 Roma in Bulgaria, but real estimates are closer to a million. In Serbia, there are about half a million, and in North Macedonia, the total number is small at about 200,000, but given the small size of the country, this is almost 10% of the population.

Some Balkan Gypsies came to Crimea with the Byzantine Greeks, and after the annexation of the Crimean Khanate to Russia in the 18th century, they spread throughout Ukraine and the Caucasus. These Gypsies lived under the rule of the Ottoman Empire for a long time and preserved the traditions characteristic of Turkey. Some of them, such as the Crimean Gypsies, converted to Islam, and the Carpathian Gypsies who settled in Hungary lived for centuries under the rule of Hungarian kings and adopted the Hungarian language, Catholicism, and culture. Now their territory is not much larger than the old borders of the Kingdom of Hungary, and they live in Slovakia, Serbia, Ukrainian Transcarpathia, Austria and a little bit in Poland. These Roma suffered the most from the genocide perpetrated by the Nazis, but even now there are up to 870,000 Roma living in Hungary, which is almost 9% of the country’s population. It is interesting to note the fate of the so-called Gypsies-Vlachs who lived on the territory of modern Romania.

In Romania, the authorities of the Danubian principalities turned the Roma into slaves, and for centuries they worked for local feudal lords in Wallachia and Moldavia. Gypsies could be bought and sold, and some of them escaped from slavery to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which led to the emergence of Serbian and Ukrainian Gypsies, who today live not only in Ukraine, but also in Russia, the Caucasus and the Volga region. In the 1860s, slavery was abolished in Romania and the Roma began to spread throughout Europe, giving rise to diasporas such as the Calderas and Lautarian Gypsies who today live from the United States to Russia and from Norway to Italy. These Gypsies differ from all the others not only in the huge number of borrowings from the Romanian language in their dialects and the national costume, reminiscent of Romanian clothes, but also in their occupations. They are mainly blacksmiths, turners, welders, and mechanics who make a living from various crafts. To this day, Romania remains the most Roma country in Europe: according to the 2010 census, the number of Roma in Romania exceeds 600,000, which is 3.3 percent of the population. This already makes the Roma the second largest ethnic minority in Romania after the Hungarians, and this is an official figure that, like all Roma censuses, is grossly underestimated. According to the European Commission, about two million Roma live in Romania, which is more than 8 percent of the country’s total population. In this regard, there is even a popular opinion, which I have heard many times, that all Romanians are Gypsies or that all Gypsies are Romanians. Of course, they are two different peoples, but Romania has indeed had a significant impact on the history of the Roma, and many words in the Romani language are borrowed from Romanian. In Russia, the Gypsies appeared relatively late, and in Kievan Rus there was no Gypsy camp, as in the cartoon “Alyosha Popovich”. This was simply not possible until the 16th century, and the Gypsies were not heard of in Russia until the 16th and 17th centuries, when they began to be referred to as a nomadic people living among Germans and Poles. However, since the 18th century alone, our country has experienced four migrations of Roma from the West. Indeed, the Roma who came to Russia came from the West.

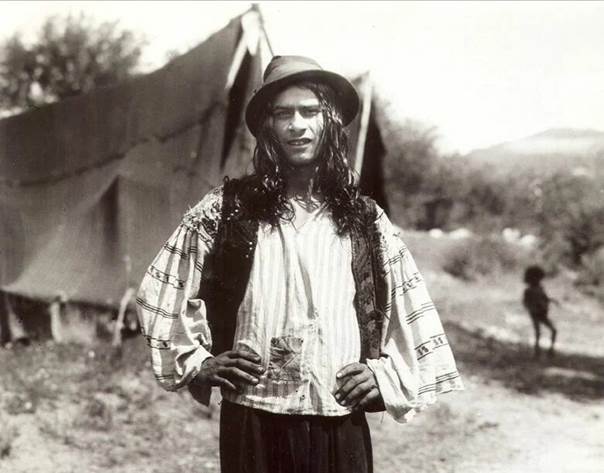

The people known today as the Russian Gypsies are descendants of German Gypsies who, fleeing persecution in Western Europe, moved farther and farther east until they reached what is now Belarus. More precisely, they arrived in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which at that time was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Other groups of their caravans ended up in India, in particular in the Leningrad region, which at that time was under Swedish rule, as well as in the Danubian principalities in what is now Ukraine, which at that time was also part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Thus, the Roma first appeared in Russia in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, although the Russian-Polish border at that time was unstable due to frequent wars, making it difficult to determine the exact date. The first written mention of the Gypsies in Russia is a document of 1699, in which a certain A. Tsygan sells a horse to the servant of the voivode of the city of Zmeev. In 1703, Peter the Great’s troops captured Ingria from the Swedes together with the Gypsies already living there. At the beginning of the 18th century, the first mentions of Russian Gypsies appeared in the Smolensk province. Interestingly, they spread very quickly throughout Russia; by 1721, the English traveler John Bell reported seeing a gypsy camp near the city of Tobolsk in Siberia. When asked by the local authorities, the Roma replied that they were from Crimea and were on their way to China, making them one of the first (if not the first) Roma camp in Siberia. Gradually, the Russian Gypsies spread throughout northwestern Russia, as well as in the Black Earth Region and the Caucasus. These were the gypsies from Pushkin’s poem and Gogol’s stories, who lived in caravans, traded at fairs, stole horses, and at night sang and danced in the forests.

Later, no less famous Ursar gypsies appeared in Russia, who caught and trained bears and performed with them at fairs. Although there were only a few Ursari, they were very famous and memorable. Catherine II considered all Gypsies in Russia to be state peasants and treated them accordingly, that is, like all serfs, they were forbidden to leave their place of residence without a passport. The first wave were Gypsies, speaking a mixture of Romanian and Hungarian, who came to Russia in the mid-19th century to escape persecution in their home countries. They were called “calderas” because they were engaged in metalworking and tinsmithing. They preferred to settle in cities, where they offered their services to the local population. They were also known for their ability to cover long distances and often used trains as a means of transportation. The second wave of Roma migration occurred during World War II, when Roma from Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova and Crimea fled to the east to escape the Germans. Many of them settled in the Samara region after the war. The third wave of migration occurred in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Roma from Uzbekistan, Central Asia and Hungary came to Russia in search of better opportunities. The reasons for this migration were the same as those of other migrants to Russia, including a lack of economic opportunities in their home countries.

Only the details have changed. For example, the Balkan and Romanian Gypsies are the same as the Calderari or the Servians. Even when they lived in Byzantium, they were called blacksmiths, and they still retain this profession. Originally, the Gypsies were blacksmiths in the literal sense of the word. They forged nails, sickles, axes and all kinds of agricultural tools in their camps, traveled to villages and sold their products to peasants. For example, in Gogol’s “Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka”, gypsies forged iron at night in secluded places, like Poltava blacksmiths. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mass production began, and the Kuznetsk calderari turned into tinsmiths. They used to make a living by repairing and mending dishes, and now they have become mechanics, welders, and so on.

The Russian Gypsies, for example, were distinguished by the fact that their men traded horses, and the women divined and sang for money. I think you are more familiar with this image, and literally all Russian writers have touched upon it. This is how they lived until about the middle of the 20th century. Now horse breeding is gradually being replaced by car trade, especially among the Roma of the Samara region. Gypsy women, who sang and divined for money in villages and at fairs, first moved to the cities and began to sing in restaurants. Then whole clans of professional gypsy artists arose from them. So, with the onset of progress, the Gypsies somewhat modify their professions, but the main principle remains to engage only in those professions that their ancestors were engaged in, and this is mainly theft and begging, which are also associated with this tradition.

For the Roma, begging is not considered shameful, and for many of their tribes it is the main source of income. By the way, it has always been a woman’s job. Roma women are mainly engaged in begging. Moreover, girls are taught this craft from the age of six, and the reason is also rooted in Indian traditions. Not only in India, but also in the Middle Ages, there were guilds of professional beggars in many places. In Russia, they went to collect leftovers in certain regions, and in the 19th century, the Gypsies, with their inherent desire to preserve traditions, simply preserved this source of income. Even in the 21st century, they don’t see anything wrong with it for the same reasons, and they also don’t see anything wrong with stealing. This, too, one might say, is their caste occupation. In other words, most Roma earnings are relatively honest, but stealing with the carelessness of a “gajo” is not a bad thing, and that doesn’t even stop them from realizing that most Roma are considered thieves.

When Jesus Christ was being led to be crucified, a gypsy stole the last nail that was supposed to pierce his heart. When the gypsy was asked about this, he replied that he did not take it, but swallowed it before God. This act prolonged Jesus’ life a little. God told the Gypsies that they would live by their cunning, and this is how the Gypsies developed their craft traditions. They do not value education and school very much, because the traditional professions of the Roma do not require diplomas. They believe that education can lead to assimilation, and they will cease to be Gypsies. Until the middle of the 20th century, the Roma did not receive an education in Russia. In 1956, a decree was issued obliging Roma to attend school. However, even now, Roma children mostly attend only primary school. Roma parents are hesitant to send their children to school because they fear that education could lead to assimilation. Roma children who do attend school often do not continue beyond primary school and attendance is irregular. School teachers working with Roma children are encouraged to be mindful of their cultural differences, as described in the 2013 Handbook on Roma History and Culture. Many Roma children start school at the age of 6 or 7, but not all attend regularly, especially during the cold season or during family events such as weddings and funerals.

Unfortunately, Roma children often miss school and, for various reasons, interrupt their education after the fifth or sixth grade. However, those teenagers who overcome this fatal barrier continue to study relatively steadily, graduating from 9-year school. Some of them are trying to continue their education and get a full 11-year education. However, the truth is that by the 2010 census in Russia, only a small proportion of them (8%) had completed secondary education, and three-quarters of Roma had completed only primary school. Less than one percent of them had higher education, and only 16 people had an academic degree, while in Russia as a whole a third of the population had higher education.

Although Russian parents are obliged to provide education for their children, the Roma themselves and, apparently, the competent authorities do not care either. Some Russian regions are trying to solve the situation by creating separate classes and schools for Roma.

One idea supported by some Roma is to provide education in the eighth grade up to the age of 15, which would be a more or less adequate education, but without the possibility of going to university. However, human rights activists strongly object to this idea, seeing segregation in it. However, the Roma themselves are good at separating themselves from the outside world and prefer to have purely contractual relations with the authorities.

It is important to reiterate that it is difficult to speak of the Roma as a single group. Gypsies are several completely different peoples, each with their own traditions, which have also changed over time. If we talk about nomadic Gypsies, such as the Russian Gypsies or Serova, they live in camps, each of which consists of two or three related clans united for nomadism. The head of the camp, usually a gypsy baron (who is not really a baron, but the head of the most authoritative family in the camp), leads the organization of the camp. In general, the family for the Roma is sacred, and their whole life is built according to the clan principle. For the Gypsies, it is very important which clan you belong to. They live in large families consisting of several generations. Gypsy traditions include endogamy, i.e. marriage within one’s own clan.

It used to be common for Roma to marry at an early age, with some parents arranging marriages for their children as young as 9 years old. Although the practice is no longer as common, the 2010 census showed that 20% of Roma women were married before reaching the age of majority. In addition, 5.7% of Roma men reported being married at age 16, and more than a quarter of Roma mothers reported having given birth to their first child before the age of 18, including 7% who gave birth before the age of 16. These figures are much higher than in Russia as a whole, where less than 0.5% of people marry or have children before reaching adulthood.

The Roma community often ignores legal age limits for marriage: some couples do not register their union until the bride turns 18. Children born to their mothers before they reach the age of majority may not be officially registered. Roma society is organized according to a patriarchal principle, in which the eldest man in the family is the head of the clan. This means that the younger members of the family, including the sons, must be subordinate to the elders, even if the age difference between them is only a few years. Each Roma family has its own occupation, and they provide for themselves when the clan moves to a new place. Gypsy clans share territory among themselves, and it is strictly forbidden to enter the territory of another clan. Parents often want their children to stay with them for as long as possible, as they are a valuable workforce.

In Roma culture, adult sons can usually separate from their father and start a family of their own only after they have children of their own. There is even a symbolic gesture for this: the daughter-in-law, the wife of the son who wants to separate, must cook food separately from the mother-in-law and in her own pot. After that, the head of the family must allow the son to start an independent life. By the way, there are cases when parents did not want to let their children go for decades so as not to lose the workforce, and in the end they solved the problem only with the mediation of the master.

Regardless, when a son separates, he loses his right to inheritance. The property of the Roma clan passes to the youngest son, who cannot separate and lives with his parents until the end. To deal with current issues between clans, there are two organs of direct democracy in the camp: the s’oda (assembly) and the senda. S’oda is a gathering of all the adult males in the camp who deal with current issues, such as where to migrate and where to work. Senda is literally a gypsy court. If one Roma has a grievance against another, he can convene a senda, a council of elders to hear the case. According to custom, the Senda should sit until a decision has been reached that will help resolve the dispute in a way that satisfies the entire camp. After that, the decision becomes final.

In fact, Senda has some pretty serious powers. It is rumored that at such meetings a gypsy who has violated the laws of the camp may be ordered to be killed. Of course, officially, according to official sources, nothing of the kind has been practiced for more than a century. But what is known for sure is that by the decision of the Send, the Roma can be expelled from the camp for bad behavior. Such a person becomes magirdo, which means “unclean” in Romani. This means expulsion from the Roma community and from the camp, a kind of civil death. Again, we can recall the character of John Wick Chapter 3, where this status is denoted by the Latin term “excommunicado”. In reality, the gypsies don’t treat magirdo as harshly as they do in the movie, though they are still severe. Magirdo is forbidden in any Roma camp, and physical contact with them is also prohibited. If someone accidentally shakes hands with a magird, he himself becomes defiled. To prevent this from happening, the magirdo must warn everyone of his status. However, a person can move out of the impure status, which is imposed for a limited time, usually a year. After that, the person can try to return by the decision of the same send. By the way, there is a very interesting ritual during the taking of magirdo…

Upon his return to the camp, all the elders should greet him by shaking his hand to show that he has now been cleansed. However, in the case of serious offences, such as the rape of a gypsy girl, the person is expelled from the camp permanently. Gypsies from other unrelated families may join the camp, but in Romani culture they are considered second-class citizens and are called “kezlogia”, which literally means “servants”. According to Roma customs, it is not entirely forbidden to work for someone from another family, but it drastically lowers a person’s social status. Gypsies, who live in tents and earn their living by trading and begging, have a somewhat simpler system. The Kaldarash, on the other hand, make a living by making utensils, and now not only dishes, but also welding, repairing cars, etc. The Kaldarash have an equivalent of a camp, which they call “kompani” in their dialect. It is only an association for living together and moving around, and in order to produce they have to create special associations or cooperatives, which in their language are called “artels” or “wordtech”, which means “partnership”. These cooperatives follow quite capitalist rules, such as allowing non-family members to be employed. However, they usually do not allow “gaja” or non-Roma to join the cooperative. For example, a gypsy cooperative for the production of metal gates can gather everyone who understands the business, and a gypsy worker who becomes a “vajda”, a kind of foreman, hires his fellow tribesmen as workers. Often the “waida” and the “baro” are the same person, and all equipment and enterprises are usually registered in the name of “vajda”. However, the distribution of profits is also governed by traditions, usually based on the principles of cooperatives. When all employees receive an equal share of the profits, the waida as the eldest receives two shares. Economic relations in the Roma world are quite unique. Since the written culture of the Roma is practically non-existent, it is customary to work without a contract not only with the Gadje, but also with other Gypsies. Instead of signing documents, they have a ritual where they hold an icon and say an oath. The oath is, “Let me die if I lie, or let Haman turn me into an outcast.” If someone breaks this oath, it is considered a serious crime in Roma circles. Usually, for such violations, the “senda”, the gypsy court, prescribes expulsion from the camp. All sociologists who study the Roma note that this people has no concept of personal property.

Most likely, this is a relic of nomadic life, when you can’t carry much in a cart, so even today Roma can easily sell all their possessions if they need to, for example, pay a large bribe to the authorities, because, from their point of view, they can always earn more. Let’s talk a little bit about the position of women among the Gypsies, because there are many myths around it, many of which originated in the literature of the 19th century, where the Gypsies were portrayed as defenders of primitive freedom, and Gypsy women as freedom-loving seductresses who could drive any man crazy. I’m sure you’re familiar with such literary heroines as Esmeralda from The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Zemfira from Pushkin’s poem or Carmen from Prosper Mérimée’s novella. This myth arose because Roma women earned their own money, including by performing at festivals and in restaurants, which was unthinkable in the patriarchal 19th century, especially for the nobility, where women were first and foremost mothers and keepers of the hearth. Indeed, there were many cases of wealthy Russian, French, and Spanish nobles falling in love with gypsy women who performed in theaters and restaurants, but such love was rarely mutual. I emphasize that Roma traditions still severely limit contact between Roma and non-Gypsies today, and in those days such relations for a Roma woman could lead to expulsion from the community, so only a few dared to do so. In general, gypsy women simply persuaded their admirers to give them gifts, and rings, bracelets and gold chains given as gifts often did not become the property of a particular girl, but went to the general income fund of the family.

From this it follows that among the Gypsies the lower part of the female body is called mogiripen, and the woman’s skirt is also called mogiri-pen. Therefore, traditional gypsy women wear two skirts, the lower of which is called poga, and the upper skirt Married gypsy women wear an apron to protect others from ritual impurity. Women’s shoes are also called mogiri pen, and the fight against impurity haunts the gypsy woman throughout her life.

Sex life is strictly controlled and the bride must be clean. If this is not the case, the girl returns to her parents’ home, and her parents reimburse all wedding expenses to the groom’s family. Although the Gypsies led a nomadic life, the life of women in the camp was surrounded by many prohibitions. Immediately after the wedding, a woman had to put a headscarf on her head and an apron on her skirt, which protected others from impurity. A woman was not allowed to cross the stream from which water was taken for drinking, to touch her skirt to a cooking pot, or to step over the yoke of a horse.

In addition, a woman who was inflamed by a quarrel was credited with the ability to verbally defile any object. In this case, it also had to be discarded. If a woman sat next to, for example, dishes or other household items, or simply touched them with her skirt, the contents were considered defiled and were either thrown away or sold to non-Gypsies. The women sitting in the back of the gypsy carts that the women rode even made a special device like a trunk, called a shiryad, to put dishes, samovars, and so on. So that the woman sitting in the cart could not defile them.

Men’s and women’s clothes were always kept separate, and they also had to be washed separately, as well as clothes for the upper and lower parts of the body. Moreover, if a married gypsy woman is above a room, i.e. on the second floor, then everything under her on the first floor can become unclean. Therefore, a gypsy man must always make sure that the woman is not above something. And yes, it also has a significant impact on social status. All power in the camp belongs to men, and women are subordinate by definition. A woman’s social status can only appear with age. An old woman who has borne many sons to her husband ceases to be a woman in a sense, and her opinion is listened to with equal respect as the opinion of an elder.

At present, the situation for the Roma is gradually improving, at least in some Roma communities that have begun to take into account the interests of women in marriage. In the 21st century, Roma have come to terms with the concept of divorce and the fact that marriage is not necessarily for life. For example, in Poland in the last few decades, a new tradition has emerged, according to which the bride is given not only household items such as dishes or bed linen, but also economic assets such as an apartment, car, shares, etc. This dowry remains the property of the woman and her husband cannot claim it. This is done so that the Roma woman is not afraid of being left without means of subsistence in the event of a divorce.

The relations of the Roma with the populations of the countries in which they lived were always wary, although the fact that the Roma were Christians did not help their cause. The way of life of the Roma has always led to conflicts with the locals. As I have already mentioned, there were laws against the Gypsies and cases of enslavement of the Gypsies. In Hungary since the 18th century, there have been rumors that Roma were eating people, and under torture, the Roma confessed to killing and eating several Hungarian peasants. There was never any proof of this claim, but even in the 20th century, stories appeared in newspapers and magazines about Gypsies as cannibals. Naturally, conflicts between the Roma and the locals broke out regularly, and from time to time ideas arose in various European countries to expel or exterminate the Gypsies.

The most terrible moment in the history of the Roma was the Roma Holocaust, or as the Roma call it, samudaripen, which means “mass murder”. This refers to the murder of all Roma by the Nazis, not only in Germany, but also in other parts of Europe. Restrictions on Roma have always existed in Germany, but during the Third Reich they mainly affected those Roma who were not German citizens but had traditionally lived there as Sinti. After World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, Roma poured into Germany from the region, leading to predictable consequences such as an increase in crime.

This allowed German right-wing groups to start talking about the Roma threat even before the Nazis. In the Weimar Republic, the first measures to restrict Roma were taken at the local level, with the establishment of the Roma Information Service at the Berlin Police Headquarters. In Bavaria, in 1926, a law was passed to combat vagrancy among the Roma. This law established that Roma and similar nomads had the right to move only with written permission from the police authorities, and allowed Roma to be sent to forced labor camps. Roma were also forbidden to camp in public parks and use public baths.

The question of getting rid of the Gypsies in Germany was raised in May 1936, before the Olympic Games, when the Reich Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, authorized the chief of the Berlin police to carry out a general round-up of the Gypsies. All Roma in the capital of the Reich were expelled from the city limits, and a camp was set up for the Berlin Gypsies, which was officially called the “Marzahn site”. In reality, it was a sorting concentration camp, through which about 1,500 Roma passed during the war.

On December 8, 1938, Himmler issued a circular on combating the Roma menace, which called for the regulation of the Roma question on the basis of racial principles. By 1930, it was already known that the Gypsies originated in India and were therefore Aryans, and even Nazi science, for all its ideology, could not simply deny this fact. As a result, for the final solution of the Gypsy question, the ideologists adopted the following concept: the Gypsies were originally Aryans, but in India they began to mix with representatives of inferior races, and now they have even fewer Nordic features. The German researcher Hans Günther noted that the Gypsies did retain some Nordic traits, but they belonged to the lowest strata of the Indian population. In the process of migration, they absorbed the blood of the surrounding peoples and thus evolved into a race in which Eastern and West Asian traits were mixed with Indian, Central Asian, and European traits. The reason for this mixing was their nomadic way of life.

To deal with this unfamiliar problem of the Gypsies, Robert Ritter, a doctor of psychology, was sent to investigate. This scientist focused on the biology of vagabonds, slackers, and crooks from racially alien groups.

He led the hygiene effort in the Imperial Health Service. The rhetorician divided all the Gypsies into three categories. Pure-blooded Gypsies are those who, on the basis of skull size and other anthropological calculations, have been identified as Nordic Aryans. They were released and kept alive for scientific research. Only 300 of them survived the entire period of the genocide. Socially adapted or assimilated Roma living in the cities were to be sterilized, but their lives were spared. The Nazis developed a simple method of sterilizing women by inserting a dirty needle into the uterus. This usually led to a painful inflammatory process that could lead to blood poisoning and death, and no medical care was provided. The vast majority of Roma were identified and exterminated, which was similar to the Jewish Holocaust.

Roma were sent to Treblinka, Auschwitz and Sobibor as refugees. The Balkans became the centre of extermination, and in Croatia no distinction was made between the Roma in the camps and the assimilated Gypsies living in the cities. Hermann Gelendreiner, a Roma from Munich, described his family’s fate: “In the summer of 1943, my parents were told that they had to move from Munich to Poland just because they were Gypsies. There were about 100 of us in total, including all my relatives on my father’s and mother’s side. We all rode in the same car, not knowing where and why we were being taken. Both of my uncles were officers in the German army and wore their military uniforms for the journey, and my grandfather, a veteran of the First World War, attached medals and orders for bravery and courage to his uniform. None of this saved us and meant nothing to the Nazis who accompanied us, who beat old men with medals on their chests, pregnant women and children with rifle butts. To them, the Gypsies were only inferior people who threatened the purity of the Aryan race.”

Two weeks later, when people dying of thirst and hunger arrived at Auschwitz, about a hundred corpses fell out of the wagons. They were immediately sent to the crematorium ovens, as were the Jews. By the way, the Roma were also told that they were being taken to some transit camps, and some were even told that they would be taken to Scandinavia or other neutral territory. But no one knew what was going on in Auschwitz at the time. Allied intelligence already knew what was going on, but I mean it in the occupied territories.

Vasily Grossman, in his essay on Treblinka, also mentioned that an entire Roma camp from Romania arrived at the camp on their own, without guards, and was completely exterminated at Auschwitz.

The text describes how Dr. Mengele conducted experiments on Gypsies, with the least harmful of which involved forcing prisoners to jump off the roof of a building to study how their leg bones would heal, or submerging people in icy water to see how long they could survive before losing consciousness, and then trying to revive them with the help of invited prostitutes. The extermination of the Roma began as early as 1941, when some German soldiers hunted down the camps and killed their inhabitants. The situation varied from country to country, most actively in Serbia, where the local government ordered the execution of Roma on the spot or their deportation to Auschwitz and Sajmište. In neighboring Bulgaria, however, a different policy was pursued: the authorities banned marriages between Roma and non-Roma, reduced the distribution of food rations to Roma, but did not allow genocide. Romania had a strange policy of exterminating Gypsies, but some of them were also drafted into the army and fought on the Eastern Front. In the Soviet Union, the extermination of Roma began in December 1941, when they were asked to come with their belongings for resettlement, and those who came were shot. Later, the killers searched for those who had fled to the countryside. In Belarus, for example, only about 800 of the 15,000 Roma who lived there survived. The text cites eyewitness accounts of the extermination of Roma in Postavy, Belarus.

In Latvia, the Roma were lucky to some extent, they were shot contrary to the well-known expression in the nationality column in the passport. Therefore, some Roma managed to buy documents and become full-blooded Latvians. In Lithuania, the local occupation authorities preferred not to exterminate the Roma, but to use them for forced labor. Most of the Roma survived. In Crimea, the Gypsies who professed Orthodoxy were exterminated. Only those Crimean Roma who professed Islam survived. The Crimean Tatars convinced the Nazis that they were just one of the ethnic groups of the Crimean Tatars. By the way, a similar story happened to the Karaites in Crimea, who were also considered Tatars, not Jews. The total number of victims of self-determination is still unknown, but in any case it is significant. There are documents about the extermination of 130,565 Roma in concentration camps, but the maximum estimates of those killed, including in the occupied territories, range from 800,000 to 1.5 million people. But even without the Holocaust, the 20th century dealt a heavy blow to the Roma. The era of society changed from agrarian and rural to urban and industrial, and the Roma way of life did not fit into the new reality in Russia. In addition to the objective change of epochs, such circumstances as the period of the existence of the USSR with its socialism also overlapped. This is not to say that the Soviet government hated the Roma, on the contrary, in the 1920s and 30s, the Bolsheviks actively supported the rights of minorities to develop their culture within the USSR.

In 1925-1928, significant funds were invested in the development of the Roma people through the All-Russian Gypsy Union. Actor Ivan Roma Lebedev, a Roma activist, recalls that the nomadic Roma were in no hurry to abandon centuries-old customs and traditions. They did not know how to farm, how to build, how to read or write. They were afraid of facing the unknown. Lebedev and four other young Roma fought fiercely against the old order, which hindered progress and expected justice. They argued with their parents, left home, and continued to fight.

In the early 1930s, there were three national Roma schools in Moscow, where instruction was conducted in the Romani language, as well as Roma pedagogical courses, which in 1932 were transformed into the Roma branch of the Pedagogical Institute. The Romani language had to be largely created from scratch, as there are many dialects among the Roma that are related to each other but vary greatly due to numerous loanwords from the languages of Europe.

In the 1920s, an attempt was made in the Soviet Union to create a unified Romani literary language based on the Russian Romani dialect. In 1926, under the leadership of philologist Maxim Sergeevsky, the Gypsy alphabet was developed, on which books were printed. From 1927 to 1938, about 300 books were published in the Romani language, including primers, textbooks, translations of the works of Pushkin, Leo Tolstoy, Korolenko, Gorky, Prosper Mérimée, and, of course, Marx, Lenin, Stalin and other party literature.

In 1931, the first gypsy theater in the Soviet Union and the world “Roman” was opened. For the first 10 years, performances in the theater were held only in the Romani language. During the intermissions, the interludes were performed in Russian with a brief explanation so that Russian-speaking viewers could understand. In general, everything was fine in theory, but in practice everything turned out to be not very successful. To begin with, only a minority of Roma were enrolled in schools. Even now, three-quarters of the Roma are confined to primary school, let alone the first half of the century.

In addition, literature in the Romani language was incomprehensible to most of the inhabitants of Servo or Calderas. In general, the demand for new Gypsy literature was small, and it was not possible to create a Gypsy-speaking intelligentsia. Most of the Roma activists came from Moscow and Leningrad artists who were well adapted to the bohemian environment of the capital and spoke Russian. Thus, the entire Gypsy cultural project hung in the balance and depended solely on the wishes of the party.

In the second half of the 1930s, the party’s policy changed significantly, and a course was taken to create a unified Soviet culture based on Russian culture and language. In such conditions, there was no one to protect the Romani language and culture. From 1938 until Stalin’s death in 1953, no books were published in the Romani language at all. With the beginning of the “thaw”, books by Roma authors began to be published again, but only in the Russian language. The Romny Theater was translated into Russian in 1941, and the Roma schools were first translated into Russian, and then completely ceased to exist.

In general, the project of Europeanizing the Roma and turning them into one of the minorities of the Soviet Union by developing their culture failed. The Roma stubbornly continued to adhere to their traditions, and traditional Roma occupations did not fit well into socialism. At the same time that Moscow tried to create a new Roma culture, most Roma in the Soviet Union faced serious problems. The first blow came from collectivization, after which it became impossible to own a horse from 1932, and the Gypsy horse trade, on which many Russian Gypsies and Servians lived, collapsed, emptying Moscow’s horse markets, where Gypsies used to trade.

The Soviet authorities tried to offer an alternative in Ukraine, and in Belarus they tried to create Roma national collective farms where Roma could continue to breed horses as part of collective labor. However, all these collective farms were short-lived. As I have already mentioned, the Roma people have a problem with collective work on a clan basis. When the article “Dizziness from Success” was published and people were allowed to leave the collective farms, the Gypsies were the first to do so. It was easier for them to leave than for settled peasants. The few Roma collective farms that survived until 1941 were either destroyed by the Nazis or all of their workers fled during the evacuation. After the war, the collective farms were not restored, and in 1956 the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree prohibiting the Roma from leading a nomadic lifestyle. The decree tightened the laws on the registration of Roma engaged in vagrancy, which the Roma found a way to circumvent. In fact, the police only chased and chased those Roma who traveled in traditional caravans and on horseback. The decree forced most Roma to settle, although some found ways to avoid it. The decree put the Roma in an ambiguous position. On the one hand, they could rise through the illegal trade in scarce goods, but on the other hand, state regulation after 1956 did not prevent the Roma from engaging in traditional trades. By the 1970s, the mass industrial production of goods such as pots had almost completely displaced gypsy tinsmiths from this gray area.

In some countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, Roma political parties have been registered since 1970, and there is the World Roma Council, which holds congresses. The results of these efforts have been mixed. On the one hand, they have definitely drawn the attention of governments around the world to the problems faced by the Roma. Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Spain have significant Roma populations. In 2005, these countries signed a declaration pledging to invest in the development of Roma and to combat discrimination. In Sweden, the Roma have been officially recognized as one of the five indigenous peoples, which gives them certain privileges, such as the obligation of local authorities to establish Roma campsites. In Russia, there have also been some initiatives, such as the Federal National-Cultural Autonomy of the Roma, which has been in operation since 1999 and aims to ensure the rights of Roma children to education. Overall, however, these initiatives have had little impact on the lives of ordinary Roma, who continue to face significant xenophobia. Wikipedia’s list of clashes between Roma and indigenous people is alarmingly long. The last time Roma made national news was in 2019, when a Russian person died as a result of a fight between Roma and Russians in one of the villages of the Penza region. After that, local residents blocked the Ural highway, demanding that the Roma be evicted. The Roma were indeed forced to leave the village, but only for a month. In 2018, historian Nadezhda Demetra, chair of the regional council of the National Cultural Autonomy of the Roma People, in her research paper on the history of the Roma in Russia, came to the conclusion that the Roma will not be able to fully integrate into society in the foreseeable future due to poverty and xenophobia on the part of the indigenous population. However, the Roma are no strangers to such circumstances.